When writing lists like these, one of the biggest struggles is figuring out how much variety should factor into your decision-making. You want to compile a list that reflects the best of the best, but you don’t want one studio or one director to completely dominate. For instance, in previous lists I’ve put on a few entries from studios like Terrytoons and Famous Studios, and although I feel the cartoons I listed were top-notch efforts, would they be as impressive if they had been made at more consistently high-quality studios like Warner Bros. and MGM? Probably not, but it’s healthy to have a little diversity.

However, this year I give up. The Looney Tunes cartoons, and director Bob Clampett in particular, absolutely dominated 1946 and I can’t in good conscience say otherwise. Eight out of ten entries on this list come from Warner Bros., and I really don’t even feel bad about it; each cartoon thoroughly deserved a mention.

1946 saw the release of the final Warner cartoons directed by Bob Clampett and Frank Tashlin, and also the directorial debuts of two of the studio’s finest animators, Robert McKimson and Arthur Davis. McKimson started out strong with the deliciously offbeat Daffy Duck short Daffy Doodles, the very good Bugs Bunny film Acrobatty Bunny and Foghorn Leghorn’s maiden voyage Walky Talky Hawky. All are fine films, but it shows what a strong year this was for the studio that I couldn’t fit any of them on the list.

However, that’s not to suggest this year was a slouch for all of the other studios. Walt Disney, in addition to releasing the feature film Make Mine Music, put out the enjoyably screwball Donald-Goofy pair-up Frank Duck Brings ‘Em Back Alive and the Academy Award-nominated Chip n’ Dale cartoon Squatter’s Rights, which featured Mickey Mouse’s first post-war appearance. Another Academy Award nominee was George Pal’s stop-motion Puppetoon John Henry and the Inky-Poo, a well-told story of man’s triumph over machines with a refreshingly non-stereotypical black cast. And speaking of stop-motion, Frank Tashlin also released The Lady Said No, which sadly only exists in a rough, partially black and white print but is still thoroughly charming.

Famous Studios had a particular good year with some unusually excellent Popeye shorts like Klondike Casanova and Rocket to Mars, as well as some amusing Noveltoons: the psychotic Jim Tyer short Cheese Burglar, the sexually-driven Blackie cartoon Sheep Shape and the supremely bitter Herman & Henry vehicle Sudden Fried Chicken. Walter Lantz kick-started its well-respected Musical Miniatures series with Dick Lundy’s excellent The Poet and the Peasant, and James Culhane bid the studio farewell with three ribald Woody Woodpecker cartoons: Who’s Cookin’ Who, The Reckless Driver and Fair Weather Friends. Terrytoons released its first few cartoons with Heckle & Jeckle, the studio’s strongest characters, and Columbia put out some enjoyably off-kilter Fox & Crow shorts like Mysto Fox, which includes an uncommonly blatant reference to Bugs Bunny.

MGM was the only studio to get any love on my list other than Warner Bros., but they still put out a handful of great cartoons I overlooked, such as Lonesome Lenny, Springtime for Thomas, The Hick Chick and Trap Happy. Also, Hanna & Barbera debuted a new supporting player for their Tom & Jerry series, the diaper-clad Nibbles, who first appeared in The Milky Waif. And Tex Avery produced Henpecked Hoboes, the first entry in his short-lived Of Mice and Men-inspired George & Junior series.

So, now that I’ve got all of that out of the way, on with the list! And I promise I’ll have more variety in 1947.

BABY BOTTLENECK

Directed by Bob Clampett; Warner Bros.

Baby Bottleneck is pure fun on every level. The story features Porky Pig and Daffy Duck attempting to run a baby delivering service when the stork becomes overworked, an idea clearly inspired by similar “baby factory” cartoons of the 1930s like Warner’s own Shuffle Off to Buffalo (1933). But with Bob Clampett at the helm, the cartoon becomes like nothing you’ve ever seen before.

The film kicks off with a series of spot gags about botched deliveries, which probably would’ve been tedious in the hands of any other director, but Clampett’s imagination and the stellar work of his animators make each scene a joy to watch. There are several dated jokes here, involving Bing Crosby’s many children, Eddie Cantor’s inability to have a boy, the Dionne Quintuplets and that ending reference to John J. Anthony of the radio advice program The Goodwill Hour, but the cartoon’s manic cartoon energy will never date. (Note: in the original print, the mother pig apparently said to the baby alligator “don’t touch that dial”, but the Production Code deemed the gag too risqué; one wonders what they thought of the cartoon’s final joke, where the Mother Gorilla expects to see her baby’s genitals and instead comes upon Porky’s face!).

On every level, Clampett makes this cartoon a treat for the senses, packing in funny drawings and crazy ideas by the truckload. This is the kind of film where an enthusiastic dog inventor pops in to show off his new creation, it blows up in his face and he ambles out the door when the gag is complete (this spirited sequence was animated by Bill Melendez). The designs of the various bucktoothed babies are the perfect blend of goofy and cute, and Clampett stretches and distorts Porky and Daffy with reckless glee, putting them through the wringer as they never have been before or since. One amazing Rod Scribner scene has Porky’s body all twisted up as he props himself up by his tongue, all while Daffy is hopping on top of him. And then there’s that amazing sequence where Daffy’s leg gets stretched out like Silly Putty, which begins what is probably the greatest walk cycle ever animated.

Clampett isn’t afraid to throw in early ‘30s-style eccentricities that most other directors had moved away from, and so we have machines suddenly coming alive to consider a situation, light-bulbs and question marks appearing above characters’ heads and a few uses of text (an explosion is punctuated by the written word “BOOM”, and even the font is funny). The music is bombastic and wonderful, featuring perhaps Stalling’s most appropriate invocation of Raymond Scott’s immortal The Powerhouse, and the voices are as good as can be; Mel Blanc’s Daffy is typically hysterical, best emphasized by a great scene of Daffy jumping from one phone to the next (animated to perfection by Rod Scribner). And the little incidental voices are just as funny (i.e. the turtle’s incomprehensible jabbering as he pours the milk out of his shell).

Even the backgrounds are daring and original. Many scenes feature the characters wandering around on a simple gradient, and in one amazing moment, Daffy is hit on the head with a tiny hammer and the impact of the blow turns the background bright red, green and orange as his head sloshes from one shape to the next. In any other cartoon that would be the standout moment, but here it’s just one of many.

BASEBALL BUGS

Directed by Friz Freleng; Warner Bros.

Certainly the most iconic animated film about baseball, and possibly the greatest of all sports cartoons (sorry, Goofy), this classic Bugs Bunny cartoon sees the smart-alecky rabbit single-handedly winning a baseball game against a gang of roughnecks known as the Gas-House Gorillas. Freleng crams in dozens of wonderful cartoon sight gags (the screaming liner that literally screams, the slow ball that inches through the air) along with supremely witty dialogue (“watch me paste this pathetic palooka with a powerful, paralyzing, perfect, pachydermous, percussion pitch”), and comes up with one of the most memorable and beloved Bugs Bunny cartoons ever released.

One notable aspect of the film is the way it presents Warner’s star rabbit with a real challenge. The Bugs Bunny cartoons of the first half of the ‘40s had mostly pitted Bugs against lame-brains like Elmer Fudd and Beaky the Buzzard, who he outfoxed with ease. Friz Freleng and Michael Maltese experimented with giving Bugs a more threatening enemy in Yosemite Sam, who debuted in the previous year’s Hare Trigger, but behind all of Sam’s bluster, Bugs hardly had to break a sweat in defeating him. In Baseball Bugs, Bugs is forced to defend himself against an entire baseball team… and not a team of simpering nitwits a la Fudd, but a bunch of gigantic, cigar-smoking brutes.

Even in the face of such adversity, Bugs maintains his nonchalance for the most part. Still, he is obviously threatened when the Gas-House Gorillas initially surround him, and he has to rush all through the city to finally triumph over his enemies (he’s still level-headed enough to read the daily news as he heads for the ball, but what can I say?). Even more so than earlier cartoons, Bugs is pitted here as the underdog, and that makes his brash demeanor and clever tricks all the more admirable. Instead of simply enjoying Bugs’ quick-thinking, the audience is actually invited to root for Bugs and cheer when he finally succeeds. Writer Michael Maltese would make a point of pairing Bugs with intimidating bullies in later collaborations with Chuck Jones like Rabbit Punch (1948), Long-Haired Hare (1949) and Homeless Hare (1950), but it traces back to this short.

And speaking of predecessors to classic Jones-Maltese collaborations, Baseball Bugs sees the birth of Bugs Bunny’s legendary switcheroo. Here he tricks one of the Gas-House Gorillas posing as an umpire into declaring him safe, but it wouldn’t be long before he was causing Daffy Duck to unintentionally bellow that it’s duck season and get blasted in the face.

THE BIG SNOOZE

Directed by Bob Clampett; Warner Bros.

Although Bob Clampett was a major talent ever since he started directing in 1937, he really hit his peak during his final few years at Warner Bros. Many of Clampett’s cartoons of the ‘40s feature a bit of a push-and-pull from the strong but conservative style of animator Robert McKimson and the zany intensity of Rod Scribner. But as Clampett’s directorial skills sharpened, McKimson’s influence over the films diminished, and cartoons like Draftee Daffy (1945) and Book Revue (1946) maintain the feverish energy of Clampett’s own personality throughout the entire run time instead of only in spurts. In late 1944, McKimson left Clampett’s unit to replace Frank Tashlin as a director, and Clampett was left with an extremely strong team of animators who jived beautifully with his approach, including Bill Melendez (who gave his scenes a strongly appealing fluidity), Izzy Ellis (who animated in an angular style reminiscent of the Tashlin unit), Manny Gould (who was known for his broad gesturing) and the great Rod Scribner, whose emotionally-driven character distortions are most associated with Clampett’s films.

It is one of animation’s greatest tragedies that Clampett left the studio when he was at his prime (given his success rate by the end of his WB stint, even one more year at the studio likely would’ve given us several more all-time masterpieces), but at least we have a marvelous farewell from Clampett in the form of The Big Snooze, his final effort at the studio. In the short, Elmer Fudd decides he’s had enough abuse from Bugs Bunny and he decides to rip up his contract with Mr. Warner. So Bugs has to win Elmer back by invading his dream and decorating it with his patented brand of Nightmare Paint. As with many final cartoons, it shows evidence of being a rush job – there’s a bit of reused animation (specifically the log-rolling bits, which are lifted from the 1941 Tex Avery short All This and Rabbit Stew), a few strange cuts (such as Bugs’ rendition of “Someone’s Rocking My Dreamboat” abruptly jolting into his next line) and even weak drawing in spots (the bit where Elmer tears up his contract in particular) – but none of this has any impact on the film’s ultimate success.

The cartoon is absolutely filled to overflowing with imaginative gags and eye-popping visuals. Setting the short mostly within a dream inspired Clampett to toss all constraints out the window (not that he had many in the first place) and the short has some of the stream-of-consciousness surrealism of the early ‘30s Fleischer cartoons, only matched up to a raucous 1940s sensibility. And just to toss another decade into the mix, the experimental visuals here predate the Cartoon Modern revolution of the 1950s; certainly that shot of neon rabbit outlines hopping over Elmer’s head was far ahead of its time. Crazy jokes and visual puns are plentiful, and Clampett, as usual, is willing to take a disturbingly strange idea like Elmer Fudd wearing a wig and a green dress and push it well past the point any other director would’ve taken it.

But most impressive of all is the way Clampett is able to reveal a lot about Bugs and Elmer’s personalities in the midst of all of this visual ingenuity. As with Clampett’s earlier Bugs-and-Elmer masterpiece The Old Grey Hare (1944), Clampett is willing to step back and examine the relationship between these characters by twisting up the formula. Even putting aside the wonderful meta-joke of Elmer Fudd quitting cartoons, the short dares to ask the question of where Bugs would be without someone to heckle, and his desperate plea to Elmer as he walks away to go fishing is one of the short’s strongest moments. And throughout the cartoon, Clampett expertly balances Bugs’ mischievous unpredictability (he can hardly restrain his glee in demolishing Elmer’s pleasant dream) and his effortless coolness (take a look at Bugs nonchalantly leaning against nothingness as he and Elmer plummet off of a cliff). Being able to nail interesting characters and unload a cornucopia of unrestrained Freudian insanity within the same film is no easy feat, but Clampett pulls it all off in the space of seven minutes. Talk about going out with a bang.

BOOK REVUE

Directed by Bob Clampett; Warner Bros.

During Clampett’s incredible final year at Warner Bros., he and writer Warren Foster seemed to be looking back at cartoon formulas of the 1930s and putting a new twist on them. Baby Bottleneck borrowed the baby factory concept from the 1933 Harman-Ising short Shuffle Off to Buffalo, and Kitty Kornered is a putting-out-the-cat cartoon following in the footsteps of films like Disney’s The Cat’s Out (1931), Warner’s Sittin’ on a Backyard Fence (1933) and Fleischer’s Hold It! (1938).

In Book Revue, Clampett tackles the books-coming-to-life genre that had a long history at Warner Bros., stretching back to Rudolf Ising cartoons like Three’s a Crowd (1932) and I Like Mountain Music (1933), and coming of age in Frank Tashlin classics like Speaking of the Weather (1937) and Have You Got Any Castles? (1938). Clampett himself had even used Daffy in such a cartoon back in 1941 (A Coy Decoy). But with Book Revue, Clampett not only created the ultimate cartoon of this type, but he effectively put the nail in the coffin. Why try another film in the genre when nothing could ever measure up?

Book Revue has no plot to speak of, nor is it a series of scattershot gags. It is instead a wild cartoon experience, totally exhilarating in its zany imagination and boundless enthusiasm. The short is jam-packed with topical references and jokes, many of which would be completely lost on modern audiences, but it really doesn’t matter, as the entertainment value comes from the lunatic energy that practically explodes off of the screen. Everything is at its absolute peak here: it’s got the greatest team of animators ever assembled (Rod Scribner, Robert McKimson, Bill Melendez and Manny Gould, all together for perhaps the only time), a red-hot jazz soundtrack from Carl Stalling (I honestly think this is the best score he ever wrote), incredible vocal work from Mel Blanc (check out his dead-on Russian Danny Kaye impression and his Oscar-worthy scat session) and a staggering amount of amazing visual gags (Daffy turning into a giant eyeball is classic). Easily one of the top ten greatest Looney Tunes ever made.

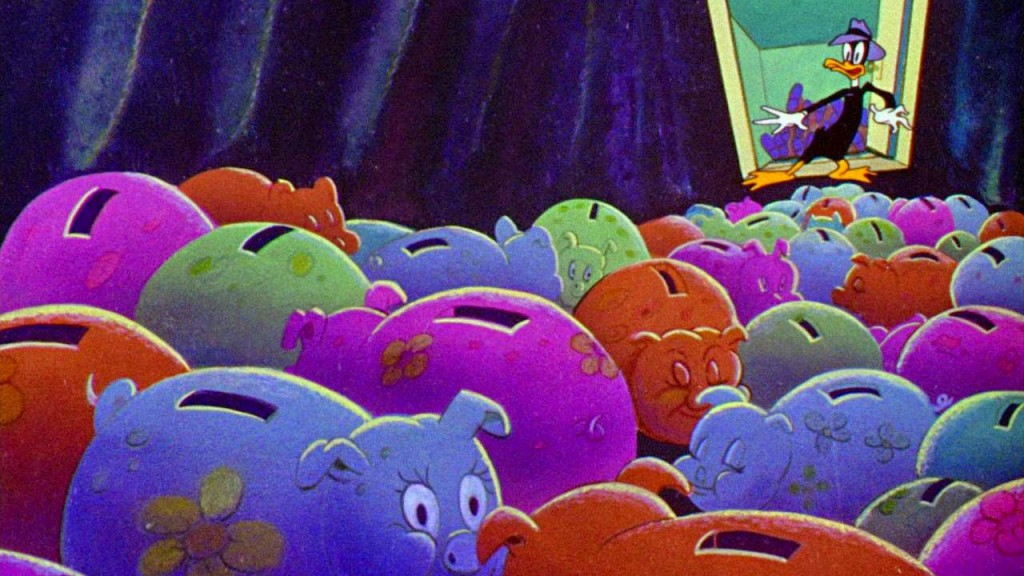

THE GREAT PIGGY BANK ROBBERY

Directed by Bob Clampett; Warner Bros.

There are a few candidates for the title of Greatest Cartoon Ever Made – Chuck Jones’ What’s Opera, Doc? (1957) and Duck Amuck (1953) instantly spring to mind – but a very strong contender would be Bob Clampett’s all-time masterpiece, The Great Piggy Bank Robbery, a stunning and hilarious comic book hallucination which sees Daffy at his most unhinged and the Warner Bros. artists at their finest.

In the cartoon, Daffy’s obsession with Chester Gould’s comic strip Dick Tracy spawns a dream where Daffy envisions himself as the famous detective Duck Twacy. When he discovers that his piggy bank has been stolen, he sets off to the Gangsters’ Hideout (broadcast in neon lights) and attempts to bring the culprits to justice. The short stunningly blends cartoony sight gags, wild animation and a seedy yet surreal atmosphere that predates the underground comics of R. Crumb and Bobby London.

Every animator here is at his absolute peak; Bill Melendez handles the early scene where Daffy declares his wish to be Duck Twacy, ultimately punching himself in the face and initiating his reverie. As Daffy hops across the screen (at one point getting right up in the viewer’s face to declare “what a man”), he has an almost balletic grace that really is beautiful (in addition to being gut-bustingly funny, of course). Izzy Ellis animates scenes like Daffy’s initial pacing around the mailbox, and Ellis’ jerky, angular style perfectly captures Daffy’s tenseness. Manny Gould has a ton of great stuff here, one particular highlight being the scene where the enormous Mouse Man bursts out of a mousehole, taking Daffy’s ego down a few notches. Daffy’s little trudge away from the mousehole, as he shrinks into his own body, is one of the most brilliant visual representations of fear ever put on film.

And Rod Scribner, the king of crazy, is truly on fire in this film. The extended sequence where Daffy reads the Dick Tracy comic book and goes through a wave of emotions is the ultimate testament to cartoon acting as an art form. Daffy isn’t doing anything impossible here, and yet his face brilliantly contorts to reveal his emotions with a vibrance that no real person could ever match. Every single frame in this sequence features a total unique and hilarious expression, and yet it all flows together beautifully to bring a remarkably distinctive character to life. Scribner has another jaw-dropping scene – more of a stunt this time, but one of the greatest ever – where a bunch of nogoodniks lunge at Daffy and all squash together into a ball as they get caught in the doorway. Already an amazing bit, but then Daffy’s body segments individually wriggle through the mess and reassemble back into Daffy when they’ve successfully braved the trip. There truly is hope for the human race when mankind can think up incredible ideas like this.

These are all wonderful standalone sequences, and Clampett does absolutely nothing to blend these distinctive artists’ styles together, to his great credit. But what makes The Great Piggy Bank Robbery such a smashing success is that these insane, ever-shifting animators perfectly bring Daffy’s inner turmoil to the screen. Has any film ever brought the leading character’s deranged mental state so vividly to life? And while some of Clampett’s detractors have dismissed his work as being zany but little else, I would ask anyone to watch this cartoon and tell me if there has ever been a stronger animated performance.

In fact, although Clampett emphasizes Daffy’s hyperactivity in a way that Chuck Jones never did, I don’t find their two versions of the character totally different in conception. As in Jones’ best works with the character, Clampett’s Daffy is cowardly (he runs screaming away from baddies like Mouse Man and Neon Noodle), selfish (he only cares about the piggy bank crime wave when he finds his own piggy bank is missing), gets caught up in the moment (he calls up Duck Twacy before realizing that he’s the same person) and has an over-inflated view of himself that seems to be a cover for neurotic self-doubt (Daffy’s Duck Twacy persona is little more than a precursor to his attempts to be a western hero in Drip-Along Daffy, a space explorer in Duck Dodgers in the 24th 1/2 Century, etc.) Daffy remains Daffy, and Clampett and Jones’ views of the character are both equally legitimate.

I should probably start wrapping up here, and yet I haven’t even begun to list all of this wonderful cartoon’s merits. What about those ingenious paintings of Dick Tracy-esque bad guys like Juke-Box Jaw and Pussycat Puss (probably the inspiration for similarly detailed still images seen in cartoons like Ren & Stimpy and Spongebob Squarepants), or Daffy’s legendary run-in with Sherlock Holmes? And have I gone through this whole thing without mentioning Rubberhead? Clearly, this is a cartoon that has a lot of great things going on in it. I’ve seen the film more times than I could ever count (hundreds of times, probably) and I’m still nowhere close to being tired of it. Even some of the best films lose a bit of their luster after the first several viewings, but if a film can give you new things to discover every single time you watch it, as well as bring a huge grin to your face, isn’t that the very definition of a classic? Any list of the greatest films ever made should find a place for this whopper of a cartoon.

HAIR-RAISING HARE

Directed by Chuck Jones; Warner Bros.

Chuck Jones started to come into his own in 1942 with the release of funny films like The Draft Horse and The Dover Boys, but by 1946 he was really becoming a master of his craft. His layout poses got stronger, the dialogue in his films got wittier and the comedy timing in his films got sharper. And nowhere is that clearer than in Hair-Raising Hare, where Bugs’ brash persona is plopped into a horror movie, with hilarious results.

The story concerns a Peter Lorre-esque mad scientist who uses the lure of a mechanical female rabbit to lead Bugs into his castle so that he can feed him to a hairy red monster. This monster was referred to as Rudolph in Jones’ 1952 follow-up Water Water Every Hare, but he’s better known by the name Gossamer, which Chuck Jones gave him in Duck Dodgers and the Return of the 24th 1/2 Century (1980). Whatever you want to call him, he’s a marvelously designed creature, so shaggy that his arms completely disappear when they’re at his sides. It’s hard to think of a more appealing and unusual design for a monster.

And Bugs Bunny is drawn beautifully here, too; he’s a bit shorter and stubbier than he would be in later Jones cartoons, but this version of the character is arguably even more appealing. The character’s expressions are wonderfully specific, from the series of wild takes he goes into when he discovers the monster behind him (Jones would later give Bugs even funnier spasms in his 1948 cartoon Haredevil Hare) to his cock-eyed expression when he first notices the mechanical bunny (gotta be one of the greatest drawings ever in an animated cartoon). And it isn’t all just static poses – Bugs’ movements are equally amusing; check out his Groucho Marx walk, or his violent hand-shaking when he announces, “well… goodbye!”

But beyond just the look of the picture, Bugs is at his most vibrant and entertaining, and the gags are consistently hilarious. Highlights are too numerous to count, although I have to mention the wonderfully timed sequence where the monster follows Bugs from behind a wall, and the fourth-wall-breaking “doctor in the house” gag that always gets the most uproarious laugh if you see the film with an audience. But perhaps the highlight of the film is the deservedly famous sequence when Bugs gives the monster a manicure, hilariously providing some idle chatter as he does his work (“I was telling my girlfriend just the other day, gee, I’ll bet monsters are in-teresting, I said…”) And then there’s that classic closing line, which gives even the much-lauded finale of Some Like it Hot a run for its money. This is masterful stuff from start to finish.

KITTY KORNERED

Directed by Bob Clampett; Warner Bros.

Alright, I’ve already unleashed all of my best adjectives extolling the virtues of Clampett cartoons like Baby Bottleneck, The Big Snooze, Book Revue and The Great Piggy Bank Robbery, so what is there left to say about Kitty Kornered?

Only that it’s one of the flat-out funniest Looney Tunes ever released. There are hundreds of Warner Bros. cartoons I love for various reasons, but the total silliness and unpredictability of Kitty Kornered makes me laugh harder than almost any other. In the film, Porky attempts to put out his four cats, but they refuse to leave. He finally scares them out by doing a shadow puppet of a dog, but the cats get their revenge by staging an alien invasion in an Orson Welles-style radio broadcast.

This was Clampett’s only crack at a Sylvester cartoon (although it was apparently his idea to pair Sylvester and Tweety together before he left Warners), and he’s obviously having a lot more fun with Sylvester’s lisp than Freleng ever did; Manny Gould lovingly draws every drop of saliva spraying off of Sylvester’s tongue every time the lisp strikes. And the other cats are equally funny, from the big dumb cat with the droopy jowls to the little guy who squeaks “I like cheese” when Sylvester asks if they are men or mice.

Part of the cartoon’s appeal is the way it seems a bit haphazard, as if Clampett is tossing anything he can into the mix to see what works, but describing his process that way doesn’t do justice to the incredible skill that Clampett and his animators bring to the table. Look at the amazing warped perspective when Porky levels a gun at the cats down a flight of stairs, or the way the background is subtly tilted to the right when the dumb cat backs up to charge at the door. There are countless little touches in the film that serve to make the big gags register, and that attention to detail made Clampett a genius.

Porky could’ve been the boring straight man here, but in many ways he’s the funniest part of the cartoon. His reaction when he suddenly realizes there are men from Mars in his bed (also animated by Manny Gould) is one of the defining moments of Clampett’s directorial career; one eye suddenly shoots open before his whole head begins to fluctuate in shock. He then starts pointing at the martians, zipping from two different windows on either side of the bed, as he desperately attempts to voice his discovery. It’s wacky and over-the-top, but also completely human. Mel Blanc does some of his best work as Porky here, too: he has a great little nervous laugh when a cat tosses him out into the snow, and I love the way he mutters “worry, worry… ooh… agony, agony” as the cats chase him through his house (listen hard, it’s easy to miss). And then there’s that amazing moment where Porky takes too long getting to the point and Clampett simply fades him out and moves on to the next scene.

But the best part of the cartoon, by a mile, is Mel Blanc’s little drunken laugh as all of the cats lean on each other and ignore Porky’s warnings. Words can’t describe why it’s so funny, just watch it and laugh your head off.

NORTHWEST HOUNDED POLICE

Directed by Tex Avery; MGM

Tex Avery showed his incredible skill at exaggerated reactions in lust-fueled classics like Red Hot Riding Hood (1943) and Swing-Shift Cinderella (1945), but Northwest Hounded Police really cemented Avery’s reputation as the King of the Wild Take. Generations of cartoonists have been inspired by this film, which captures the very essence of what makes animation such an exciting art form; actors can find all sorts of ways to convey shock and fear, but no human could ever achieve the absurd heights Avery reaches in this short.

The premise is a simple one: a wolf escapes from Alka-Fizz Prison and Droopy (referred to here as Sgt. McPoodle) follows after him to bring him to justice. Everywhere the wolf goes, Droopy shows up, and as his appearances become increasingly implausible, the wolf becomes more exasperated. It’s an idea Avery had been toying with since 1936’s The Blow-Out, one of his earliest directorial efforts, but the closest precedent is Dumb-Hounded (1943), Droopy’s first cartoon. That film features the same characters (Droopy and the wolf) going through the same premise, but Dumb-Hounded moves like molasses when compared to the fast-paced extremes of this cartoon. Northwest wastes no time getting started, and zips through each gag to avoid predictability. It begins at the most extreme point of Dumb-Hounded and then ups it in every way.

Droopy himself made a perfect starring player for Avery, even more so than characters obviously intended to helm a series like Screwy Squirrel and George & Junior. Droopy’s deadpan attitude matched with Bill Thompson’s voice made him amusing and distinctive (although Avery himself actually provided Droopy’s voice in this particular film), but he had no real identity or depth to his character, which fit well with Avery’s relentless pursuit of laughs and laughs alone. In many ways, Droopy could be considered a parody or meta-comment on protagonists in general; in Wild and Woolfy (1945), he appears to be an intruder with no real purpose to the narrative until he announces at the film’s conclusion that he’s the designated “hero” and he immediately bests the villain with a mallet.

This cartoon takes Droopy’s role as the hero to its most ridiculous extremes. He is not only unstoppable, he is completely omnipresent, able to appear anywhere at any time no matter what the wolf tries to do to get away from him. Many cartoons trade on impossibilities, but Avery was the master of taking a single crazy idea and pushing it to its breaking point. This same sensibility informed many of his other masterpieces, such as King-Size Canary (where the characters keep getting bigger), Bad Luck Blackie (where objects fall on a dog’s head every time a black cat passes him) and Magical Maestro (where a maestro conducts an opera singer with a magic wand).

Certainly Avery isn’t afraid to toss in lots of extraneous amusements along the edges (the wolf escaping out of a door he drew with a pencil, the wolf skidding outside of the film strip when he makes a sharp turn, etc.), but the cartoon’s intense focus on milking all possible laughs out of a nutty idea puts it on the top tier of Avery’s efforts. And all of Droopy’s surprise entrances are punctuated by an outrageous reaction from the wolf, each more extreme than the last. His jaw drops, his eyes bulge, his body segments fly apart and he makes every sound from a car horn to a horse’s whinny. Even the stripes on his prison outfit respond to his panic attacks. My personal favorite wild take from this short – and therefore my favorite wild take of all time, since most of the best ones are here – is in the scene where the wolf goes to the theater and discovers they are playing a Droopy cartoon. His open-mouthed, bug-eyed reaction is so big that it practically fills the whole screen for several glorious seconds. As far as the art form of funny drawings is concerned, Avery is Leonardo Da Vinci and Northwest Hounded Police is his Mona Lisa.

RHAPSODY RABBIT

Directed by Friz Freleng; Warner Bros.

This wonderful musical short could perhaps be considered Freleng’s follow-up to his 1941 film Rhapsody in Rivets, which also set cartoon slapstick against Franz Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2, but it is more frequently associated with the Tom & Jerry cartoon The Cat Concerto. Both films were in production around the same time (although work on Rhapsody Rabbit started earlier), presented their characters as concert pianists, centered around the same classical piece and showcased a feud between a pianist and a little mouse living in the piano. This was apparently a coincidence, although MGM was aware of the similarities and rushed to complete their film so it could be screened ahead of Rhapsody Rabbit for the Academy; this plan worked, and The Cat Concerto won the 1946 Oscar while the Freleng film wasn’t even nominated (Cat Concerto wouldn’t be released to theaters until 1947).

Whichever idea came first, both cartoons are among the finest examples of great animation coupled with classical music and each one is a masterpiece in its own right. Rhapsody Rabbit is an excellent showcase of Freleng’s mastery of synchronizing comic action to music, and it’s a testament to his genius that the cartoon can provoke so many belly laughs out of a fairly restrictive setup with only a limited amount of dialogue.

Freleng crams the film with funny visuals gags, such as Bugs pulling off various gloves as he prepares to perform and Bugs’ fingers getting tied up as he plays a complicated bit. Freleng finds endlessly creative uses for the piano as a prop (the keys move across the piano like a page on a typewriter, Bugs scoops up the keys and plops them down in time to the music), and Bugs even tops Chico Marx in finding entertaining ways of playing his instrument (he hops across the keys on his fingers and toes, he hits the high notes with his ear). There’s also a bit of adult humor tossed in, such as the pinup girl hidden away in Bugs’ sheet music and the brilliantly dark gag where he shoots a guy for coughing during his performance.

Complain if you will that Bugs is cast somewhat out of character, attempting to maintain control against a troublesome mouse, but his personality shines through as he confidently glides across the piano, breaking every so often to chomp on a carrot. And even when thoroughly upstaged by the mouse, as he is during the film’s climax, Bugs still has to have the last word.

SOLID SERENADE

Directed by William Hanna & Joseph Barbera; MGM

Despite ostensibly being pantomime characters, there are a great number of cartoons where Tom and Jerry speak. In The Lonesome Mouse (1943), Jerry talks like a shady New Yorker and Tom responds in a dumb-guy voice. In The Zoot Cat (1944), Tom and Jerry both indulge in hep jive-talkin’, and Tom uses some Charles Boyer-inspired romancing on a sexy girl cat. There’s also the memorable custard pie exchange in 1945’s Quiet Please! (“well, let me have it!”) and Tom’s final thought in 1944’s The Million Dollar Cat (“gee, I’m throwin’ away a million dollars… BUT I’M HAPPY!”).

There’s also Tom’s cackle of “in me power” in The Bodyguard (1944), Jerry’s Zulu gibberish in His Mouse Friday (1951) and two separate instances of Tom announcing in an echoey voice “DON’T YOU BELIEVE IT” (1944’s Mouse Trouble and 1951’s The Missing Mouse). And let’s not even get into the horrors of 1992’s Tom and Jerry: The Movie.

But perhaps the most memorable use of a voice in a Tom & Jerry cartoon is in Solid Serenade, where Tom croons the 1944 Louis Jordan tune “Is You Is or Is You Ain’t My Baby” to his girlfriend while Jerry is attempting to sleep. His performance, sung by Ira “Buck” Woods and accompanied by a cello, is a delightful rendition of the song that perfectly matches the jazzy flavor of the cartoon. It says something about the film’s success that although the song has been covered by Bing Crosby, the Andrews Sisters, Nat King Cole, B.B. King and countless others, it is most often associated with this short.

But that’s just a brief segment of this charming and hilarious cartoon, surely one of the top three or four Tom and Jerrys and a great example of 1940s animation at its finest. This was a strong period for the series, before Hanna and Barbera settled into formula in the 1950s, but Solid Serenade has an extra jolt of energy that makes it stand out even against top-notch efforts like Springtime for Thomas (1946) and Trap Happy (1946). The animation is particularly snappy and energetic, and the cool color scheme in the background nicely evokes the nighttime setting (sometimes the Tom & Jerry backgrounds get criticized for being old-fashioned next to what the guys at Warner Bros. were doing, but true as that may be, it’s hard to complain when they’re painted as nicely as these are).

The plethora of gags consist of classic slapstick (Tom gets a pie to the face) mixed with the expected Tom & Jerry sadism (there’s an iron hidden in the pie). That bit where the window slams shut on Tom’s neck and his tongue shoots out like a noisemaker rivals the famous bees-in-the-mouth scene in Tee for Two for sheer, over-the-top hilarity. Bill Hanna’s comedy timing is especially strong in this film as well, as emphasized by the brilliant bit where Tom realizes he is romancing the dog rather than his girlfriend and he slowly attempts to place his head on the ground (the scene is prefaced by a reprise of Tom’s Charles Boyer act from The Zoot Cat, and it’s just as funny the second time). The characters are also very strong here, particularly Tom, who is enjoyably arrogant as he schmoozes the girl cat and taunts the bulldog that he has tied up. With all of the elements working together so nicely, Hanna and Barbera turned out a very funny cartoon that can hold its own against the best of any other studio in the golden age and that’s quite an achievement.

Any comments or suggestions for this post? What are your favorite cartoons of 1946? Let me know in the comments below.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login