There are some fantasy, science fiction, and horror films that not every fan has caught. Not every film ever made has been seen by the audience that lives for such fare. Some of these deserve another look, because sometimes not every film should remain obscure.

Sometimes, the best critique of a work is to suggest that the maker neither shows nor tells…

Rocket Attack U.S.A. (1960)

Distributed by: Joseph Brenner Associates

Directed by: Barry Mahon

On October 4th, 1957, panic filled the air as the sky above it was filled with little beeps…

Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite humanity successfully launched into orbit, was a triumph of science that all people could have taken pride in. Unfortunately, this orb made by the Soviet Union came out in the midst of the Cold War, and was at the time just one of the milestones of the “Space Race.”

The race between the United States and the Soviet Union to get to space had nothing to do with reaching out into the cosmos, for all that was said at the time. All of its technological wonders and major milestones, from Sputnik to the Apollo moon landing program, were undertaken and done on behalf of one goal, to have the ability to launch nuclear weapons. The winner of the race would achieve the capability to fire ICBMs at an enemy that could reach their targets quickly, and use the threat of millions of deaths in 30 minutes or less to threaten the enemy if they tried to stop the winner from getting what they wanted.

Thus, Sputnik ended up causing fear among many in the west, fear that unfortunately gave us this movie:

The film opens with newsreel footage, over which we hear stock music from RFT Music Publishing and narration from an actor who didn’t bother to leave a name (lucky him). We’re given a refresher about Sputnik, how its launch changed the face of modern warfare, and a warning that “[t]he story you’re about to see would be inevitable, should the wrong people gain control of that government.”

One set of credits buried under blaring needle drop later, followed by a scene of a shortwave radio operator getting Sputnik’s signal, we’re in Washington to listen in on a meeting overseen by General Watkins (Phillip St. George) as to the steps needed to build a functional ICBM. What’s said at the meeting hardly matters, as our annoying narrator set up the gist of what everyone else was going to say and saved us the trouble of having to pay attention to any of it.

The meeting gets mercifully interrupted with no explanation while the narrator sends us to West Berlin, where secret agent John Manston (John McKay) is given a briefing: He’s sent to infiltrate Moscow to make contact with an operative to get further information on their missile program.

He must be really good at his job, as he neither asks or is told how he’ll know is contact other than just being a woman. Of course, with the laborious overarching narration infusing itself into as much of the soundtrack as possible, who needs details…?

After a long wait where the director padded the film with we get introduced to some of the colorful acts from deep within the Iron Curtain, Manston meets his contact Tanya (Monica Davis). As luck would have it, she’s in a very good position to provide intel, as she is the Soviet Minister of Defense’s mistress(!). How the NKVD would allow someone like Tanya to get that much access to the Kremlin’s inner circle is never explained; the good money’s on her being able to benefit from having that damned narrator running interference for her…

Not that the narrator helps everyone, though; we watch General Watkins stress and strain (between extended b-roll of a missile assembly line) as he tries to get one of our own satellites up into orbit to give us some (undefined) edge against the Ruskies and their machinations. It’s the best he can do, as all his carping about domestic programs getting more funding during peace time than an effective anti-missile program isn’t getting him anywhere.

(Insert Star Wars joke here…)

We then cut back and forth between Washington, Leningrad (where the missile launch facility is located; no, I don’t know why it was there either, sorry…), and Moscow, where we watch the emboldened Soviet government plot how they’re going to strike the US. In this instance, the narrator actually does more good than not; all the scenes involving Russians talking amongst themselves are in Russian, so it’s up to that obnoxious voice to tell us what’s going on. We can count on a small mercy that we didn’t get that whole “Russians speaking English for the sake of the audience” hand wave, probably the only well thought out choice the movie makes.

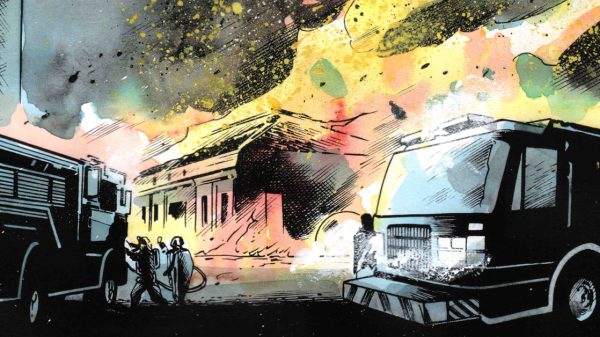

In quick succession, the narrator then fails everyone. We watch Manston and Tanya try and sabotage the missile before it launches, dying without accomplishing their objective. We watch Watkins get downhearted as the American satellite launch he pushed for ends up with the rocket blowing up after launch.

And once everyone we’ve seen so far is dead or disappointed, we get introduced to a bunch of new faces. We get a newsman catching his train into the city. We meet a businessman who was ferried by seaplane into Lower Manhattan to profiteer off Wall Street’s war jitters. We catch a truck driver (Art Metrano) teasing his wife (Jane Ross) about not wearing a tie.

Yes, a bunch of new faces getting perfunctory introductions before the end of the film, much like you see in a disaster movie; you can guess where this is going before it ends…

Calling this entire project a disaster would be kind. The main blame goes to Mahon, for things we know he did, like directing and producing the film, and things we assume were him unless another culprit can be named, such as the script and narration. As most of Mahon’s body of work consisted of cheap crime exploitation flicks and nudie films that ended up in peep show booths in the bad part of town, he was clearly the wrong person to do a geopolitical thriller with a message.

Said message was in and of itself problematic, as he espoused the dangers of the “Missile Gap” throughout the movie. The idea that the US was at a disadvantage when it came to ICBM capability was not only a gross misunderstanding of the facts on the ground, it was also dangerous. The year the film came out, John F. Kennedy ran for President on a platform that included closing the Missile Gap; two years later, this belief led to a standoff over Cuba.

If anything, one big mistake supersedes all the other miscues found in the film, over and above its horrible script, acting that wouldn’t get any of the cast into a high school play, and directorial oversight that makes this feel like an educational film that had gone terribly wrong. That mistake was timing; had the movie come out in 1958, it would have had more of an impact. Discussing the failures of the US response before the formation of NASA and the launch of both SCORE and the Explorer Program would not have subjected the film to as harsh a derisive dismissal as it received.

You could say the film’s biggest failing was its inability to conduct a first strike while there was still panic in the air…

You must be logged in to post a comment Login