We’ve reached the end of the 1940s, and we’re nearing the close of this series as well… at least for a while. But do not despair, as there are plenty of great 1949 cartoons to tide you over. This was absolutely a top-shelf year for animation, overflowing with classics from the likes of Warner Bros. and MGM. I had to work hard to get it down to ten.

This was the year that Disney released The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad, the last of the package features (the studio returned to full-length stories with Cinderella in 1950). Speaking of endings, Columbia released the last of the Charles Mintz/Screen Gems films this year (Coo-Coo Bird Dog, Grape Nutty, Cat-Tastrophy) and Walter Lantz released their last few films before a brief shutdown (the studio returned in 1951). And over at Warner Bros., Arthur Davis was retired as a director (after crafting some exceptional films like What Makes Daffy Duck and Bowery Bugs), leaving Chuck Jones, Friz Freleng and Robert McKimson as the staff directors throughout the 1950s.

But there were also some new beginnings. Chuck Jones dreamed up Wile E. Coyote and the Road Runner for his film Fast and Furry-ous, and UPA launched the nearsighted Mr. Magoo in Ragtime Bear. Over at MGM, the cartoon Wags to Riches introduced a bulldog named Spike, who would serve as an adversary to Tex Avery’s Droopy character. Confusingly, MGM had a different bulldog named Spike who had been appearing in Tom & Jerry cartoons since 1942’s Dog Trouble, but 1949’s Love That Pup was the first to introduce his son Tyke, who he would appear with regularly.

On this list, you’ll find quite a bit from Warner Bros. and MGM, along with a short from UPA and an abstract piece. Take a look:

BAD LUCK BLACKIE

Directed by Tex Avery; MGM

A black cat walks by and something falls on the bulldog’s head. It is with this simple setup that Tex Avery unleashes what could be argued as the funniest cartoon ever made, and certainly one of the highlights of Avery’s career, standing alongside classics such as King-Size Canary (1947) and Little Rural Riding Hood (1949). The film has everything you could ever want from a cartoon: extreme slapstick violence, funny characters, zany drawings, absurdly impossible ideas and an endless well of creativity. But Bad Luck Blackie isn’t just a random assortment of pleasures: as with many of his best films, Avery ties himself to a somewhat restrictive premise and then proceeds to push it as far as it can possibly go.

As with King-Size Canary, Avery is willing to go bigger and bigger, amping up a falling flowerpot to a steamship by the film’s end. But he isn’t content to simply drop things on the dog’s head and call it a day, and he sneaks a gag in at every opportunity: the cat finds a new and creative way to cross the dog’s path each time (floating by on a balloon, creeping from one tin can to another) and the damage to the dog’s body after something hits him on the noggin is typically just as funny as falling object (at one point a piano drops on the dog, and the kitten proceeds to play an off-key recital on his teeth). The inventiveness here is truly astounding. The opening scenes of the bulldog terrorizing the kitten could’ve been simple expositional setup, or even turned unpleasant and nasty, but Avery finds great humor in the sequence, cramming in gags with the ease of a true master. Even a straightforward action like the dog creeping up behind a bookshelf is made into a gag, as the dog impossibly flattens against the wall and slides over the ridges.

Avery’s comic timing is flawless, and Scott Bradley’s score is dynamite (I love the way it speeds up and goes out of tune as the black cat, newly painted white, repeatedly attempts to cross the bulldog’s path). Still, it’s the endless variations on a simple idea that make this film one of the standouts. Avery milks the concept for all it’s worth, offering numerous twists in the story to keep things interesting (the bulldog arming himself with a good luck horseshoe, the dog painting the black cat white). It’s a testament to how strongly Avery built the film’s framework that by the end of the cartoon, just the sound of a whistle causes something to fall on the dog’s head and we accept it. The black cat isn’t even crossing the dog’s path at this point, but it no longer matters, as the film’s comic rhythms have been so firmly established that the audience never questions it. The film is proudly and ridiculously impossible, and also a testament to the endless possibilities of the medium.

BEGONE DULL CARE

Directed by Norman McLaren & Evelyn Lambart

There is no shortage of excellent abstract animated films, from early innovations like Walter Ruttmann’s Lichtspiel: Opus I (1921) to latter-day digital experiments like Theodore Ushev’s Tower Bawher (2005) and Drux Flux (2008). Len Lye was a major contributor to the art form, with shorts like A Colour Box (1935), Rainbow Dance (1936) and Free Radicals (1958), and films like Mary Ellen Bute’s Tarantella, Oskar Fischinger’s Motion Painting No. 1 (1947) and Walerian Borowczyk’s Les Jeux Des Anges (1964) are masterpieces. However, if I were to make a pick for the greatest abstract animated film of all time, I might personally go with Begone Dull Care.

This incredible film was scratched and painted directly on film stock, and it was intended to visually evoke the jazzy accompaniment by The Oscar Peterson Trio (the film’s odd title apparently comes from a Scottish expression that McLaren used to hear as a boy). The short is split into three segments, the first of which responds to the music in terms of proportion. Simple drum beats and piano keys are represented with minimalist visual punctuation, whereas more complicated chords result in greater busyness onscreen. The second segment is more restrained, using white dots and lines on a black background to illustrate the simple beauty of the jazz composition behind it. Then we’re launched into the final section, which responds to the energetic riffs with frenetic and wildly colorful shapes and lines being hurled at the screen so quickly and frenetically that the film at times starts to resemble TV static.

The short is a sumptuous visual feast, full of vibrating lines, paint splatters, scribbles, specks, blots, etc., and there’s so much variation that the viewer’s interest never flags for a second. Unlike Oskar Fischinger’s more rigid works, McLaren (assisted ably by the great Evelyn Lambart) injects his film with a sense of free-wheeling wit and fun. However, unlike the explosion of color seen in Len Lye’s A Colour Box, McLaren gives his film structure by perfectly synchronizing the movements to the amazing score. The combination of what must’ve been rigorous planning with the final impression of anything-goes visual excitement is what makes Begone Dull Care one of the greatest films of its kind and solidifies McLaren as one of the world’s foremost experimental filmmakers.

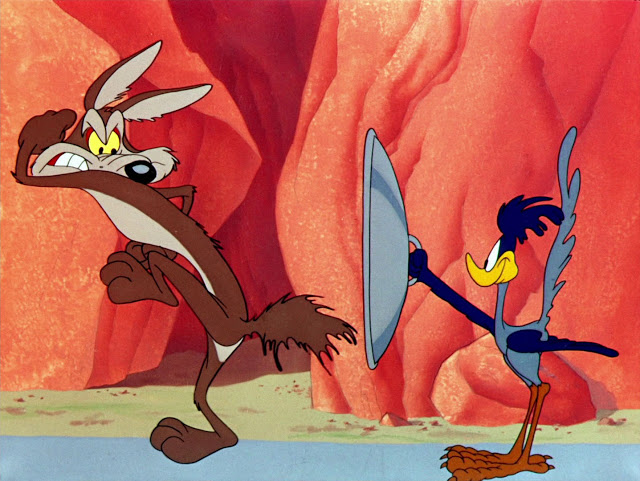

FAST AND FURRY-OUS

Directed by Chuck Jones; Warner Bros.

The conflict between the Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote is so ingrained in our heads as an endless battle that it comes as a bit of a surprise that the first entry, Fast and Furry-ous, was intended to be a one-shot. And yet, Chuck and Michael Maltese only considered making more Road Runner films when they heard that audiences had responded positively. And thus begins one of the funniest cartoon series ever made, and this first film is no exception. Gags involve rockets, TNT, superhero outfits, jet-propelled tennis shoes and even a snow machine that allows the Coyote to ski down a slope to grab onto the Road Runner, which is so gloriously ludicrous that it’s funny even before we get to the punchline.

The character designs are slightly different than they would be later (the feathers on the top of the Road Runner’s head are bushier, and the Coyote is scrawnier), and the film violates the sacred rule that the Road Runner must never harm the Coyote directly (here he holds a pot lid up for the Coyote to run into and he tosses a boomerang at his head). Still, the template is pretty much set and the elements are mostly in place: you’ve got the bogus Latin names (Accelleratii Incredibus and Carnivorous Vulgaris), a blue-print illustrated by stick figures and a product that comes from the infamous ACME, inspiring the most famous case of brand loyalty in cinema history.

Not to mention that many of the gags here seem like warm-ups to later Road Runner sequences: the Coyote dresses up as a schoolgirl, predating his hitchhiking lady disguise in Going! Going! Gosh! (1952). And the Road Runner’s sign indicating he can’t read was updated to “Road Runners can’t read and don’t drink” in Beep, Beep (1952). Speaking of Beep, Beep, the sequence in the mine feels like a revision of the Fast and Furry-ous bit with the jet-propelled tennis shoes, where the characters are boiled down to two dots chasing each other. Plus, the Coyote’s baggy “Super Outfit” anticipates the celebrated Bat-Man gag in Gee Whiz-z-z-z-z-z-z (1956). And the painted tunnel scene inspired numerous variations throughout the rest of the series, with no version of the gag quite like the last.

Jones and Maltese originally conceived the Road Runner as a parody of chase cartoons, apparently because of the obscurity of the animals used (as opposed to, say, a cat chasing a mouse) and the fact that the Coyote mostly defeats himself without much help from the Road Runner. Despite the initial hint of parody, however, the Road Runner series is probably the most iconic representation of the cartoon chase format. In fact, the films are a good demonstration of the axiom “less is more”; series like Tom & Jerry and Sylvester & Tweety could place the action in different settings, add new characters to the mix, involve dialogue, etc. But the Coyote and the Road Runner boil the conflict down to its essence, pitting two characters against each other in a barren landscape, with no talking, no added characters and no changes. Far from making the cartoons dull or unimaginative, these self-imposed limitations light up Jones’ creativity, setting an exciting artistic restriction out of which Jones pulls off masterful gag after masterful gag.

But great as the gags are – and I don’t think you could find better slapstick jokes anywhere, even in the works of Chaplin and Keaton – what truly makes the films ingenious (or, perhaps, “super genius”) and sets them on a level above most chase cartoons is our identification with Wile E. Coyote. Many cartoons demonize the predator and direct our sympathies to the victim, but the Road Runner is not really a character so much as a vague cipher. Instead, the audience commiserates with the Coyote because, after all, who hasn’t had their plans blow up in their face, or took a wrong step that sent them over a figurative cliff? In the Coyote we see our own failures and screw-ups, and this identification is largely thanks to the hilarious and poignant facial expressions Jones invents for the character. The coyote’s look of total dejection in Fast and Furry-ous when his snow machine sends him over the edge of a cliff is so funny and so true that we feel his frustration and disappointment even as we enjoy the gag. We might laugh at the Coyote, but we’re really laughing at ourselves, because in the end, life is a giant boulder hurtling onto our heads, and we think we can defend ourselves with a tiny umbrella.

FOR SCENT-IMENTAL REASONS

Directed by Chuck Jones; Warner Bros.

For Scent-imental Reasons is actually the third cartoon to star the amorous French skunk Pepe Le Pew. The first was Odor-able Kitty (1945), which featured Pepe romancing a male cat, and ended with a reveal that Pepe is married and puts on the French accent when he steps out on his wife. The character returned in Scent-imental Over You (1947), where he chases after a Mexican hairless Chihuahua, although at that point he was still referred to as “Stinky”. But For Scent-imental Reasons set the blueprint for the series, changing the location to France and giving him a permanent foil: the long-suffering cat, later referred to as Penelope in the 1954 film The Cat’s Bah. This cartoon was strong enough to win Chuck Jones his first Academy Award (despite producer Eddie Selzer’s insistence that nobody would think all that French stuff was funny), and it convinced Jones that Pepe was a character worth returning to regularly.

Indeed, Pepe is one of the funniest characters in the Warner Bros. lineup. He was intended to be a loose parody of Charles Boyer’s Pepe Le Moko character from the romantic drama Algiers (1938), but Jones later stated that Pepe’s unflappable belief that he is irresistible to women was patterned after Looney Tunes writer Tedd Pierce. Pepe’s refusal to accept reality, blissfully misinterpreting the cat’s escape attempts as flirtation, is rife with comic potential. It also offers an amusing alternative to the usual chase cartoon formula, where the “hunter” typically wants to eat the character they’re after. Pepe’s intentions are far less bloodthirsty, although the cat’s reactions indicate she would probably rather be eaten.

Pepe Le Pew was featured in a great many enjoyable cartoons, but For Scent-imental Reasons is the freshest and most inspired. The mangled French dialogue Jones and Maltese come up with is wonderfully entertaining, and Pepe’s flirtations are exceptionally written (“come, my little peanut of brittle”). The backdrops are beautifully evocative, the animation is excellent and the cartoon concludes with an amusing role-reversal that shows Jones already willing to mess with the formula he was setting up. Still, the film’s finest moment is the glass case scene, which is told through pantomime. The acting is phenomenal here, with both characters coming across vividly through their movements and expressions. The sequence involves some dark humor, as well as a rare coming-to-grips-with-reality moment for Pepe. The way he instantly brushes it off when Penelope leaves the glass case is both hilarious and revealing of his character, suggesting he can’t function except under a powerful form of denial. Great character, great cartoon.

HEAVENLY PUSS

Directed by William Hanna & Joseph Barbera; MGM

After all of the abuse Tom has taken throughout the years, who could believe that a piano crashing on his head would be his final undoing? And yet, that’s the situation presented to us in Heavenly Puss, one of the darkest and most memorable of the Tom & Jerry cartoons. In the film, one slapstick pratfall too many sends Tom on an escalator up to the pearly gates, where he attempts to get into Cat Heaven. However, feline St. Peter discovers that Tom has spent his life tormenting a little mouse, and he sends Tom back to earth to get Jerry to sign an apology so he can board the Heavenly Express before it departs. Otherwise, Tom will spend his afterlife being tortured in Hell by a canine Satan (ferociously voiced by the great Billy Bletcher).

Despite the savage violence this series is known for, there’s something comforting about the consistency of Tom & Jerry’s world (it’s hard not to grin at the opening of this film, with Tom charging after Jerry in their typical suburban residence). Seeing that consistency threatened, as it is here, is pretty unnerving and provides a clue into why many people find this short so disturbing. It’s far from the creepiest cartoon ever made, lacking the horror-fueled imagination of Swing You Sinners! (1930) and Pluto’s Judgment Day (1935), but given the amount of goodwill Tom & Jerry have built up over the years, seeing one of the characters threatened to eternal damnation is going to raise some hairs.

Probably the darkest aspect of the cartoon is some of the gallows humor in the pearly gates sequence, when Hanna & Barbera score laughs off of the grisly death of several cats (including Butch and Fluff, Muff & Puff, characters who had been featured in previous Tom & Jerry cartoons!). Still, the biggest emotional resonance lies in the scenes where Tom is begging Jerry to sign his document. This is some of the best pantomime acting in this entire mostly dialogue-free series, and Tom’s expressions of desperation are excellent. The characters’ relationship is quite strong here, and the bit where the Heavenly Express starts driving away is one of the most suspenseful scenes in cartoon history. This one cuts pretty deep for a Tom & Jerry cartoon, but at least Hanna & Barbera let us off with a reassuring ending. Later films like Puppy Tale (1954) and The Egg and Jerry (1956) veer into sentimental overkill, taking the edge off of this once brutal series, but here’s one instance where the sentimentality is justified.

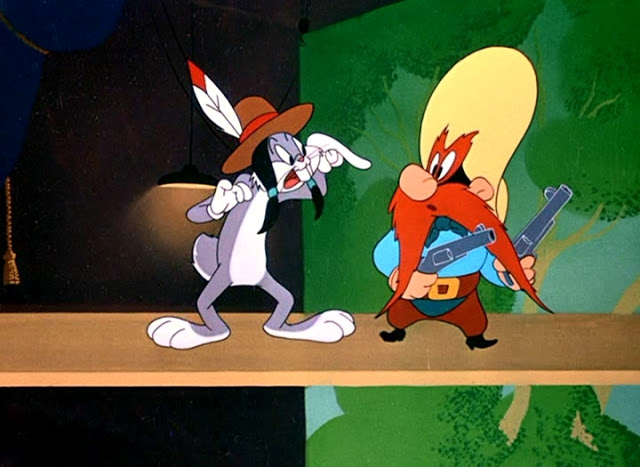

HIGH DIVING HARE

Directed by Friz Freleng; Warner Bros.

Yosemite Sam buys a ticket to a vaudeville show to see Fearless Freep do his high diving act, but Freep is delayed by a storm and has to cancel. Sam then forces host Bugs Bunny to perform the high diving act himself, but Bugs manages to turn the tables time and time again. This masterful film is perhaps Warner’s best use of Yosemite Sam, and a strong contender for director Friz Freleng’s finest hour.

The film effectively portrays the dizzying heights of the ladder to the diving board, which is key to the cartoon’s humor, not only adding tension to the scenes where Bugs is almost forced over the edge but adding punch to the gags where Sam falls off the board. The backgrounds are beautifully painted by the great Paul Julian, and he nicely evokes a scene for the various slapstick gags to play in front of. And not only that – the animation is charming, Carl Stalling’s score is typically wonderful, and Freleng’s timing is at its snappiest. The stage is set for a comedy classic, and the cartoon really delivers.

The film’s brilliance resides in the fact that it is a seven-minute variation on a single joke: Bugs Bunny tricking Yosemite Sam into walking off a diving board. The same thing happens every time, and that’s what makes the cartoon so uproariously funny. The constant repetition, combined with the ever-growing absurdity of Sam falling for Bugs’ tricks, makes Sam’s descent into a tank of water one of the most rewarding punchlines in animation history. Bugs Bunny’s methods for getting Sam over the edge are clever and funny, but the film scores its biggest laugh without even showing them. Towards the end of the film, Sam simply climbs up the ladder and then careens into the tank below. The premise has been so well-established that we don’t even need to see how Bugs tricked him at this point.

Note: In one segment, Yosemite Sam demands that Bugs open a door, adding to the audience, “you’ll notice I didn’t say Richard”. This line was a reference to a popular song “Open the Door, Richard”, which hit #1 on the Billboard charts in 1947.

LITTLE RURAL RIDING HOOD

Directed by Tex Avery; MGM

Little Rural Riding Hood is hardly the most original entry in Tex Avery’s filmography. It takes the Wolf & Red template from previous cartoons, returning to the Red Riding Hood story that launched the series in the first place with the classic Red Hot Riding Hood (1943). The animation of Red performing “Oh, Wolfy”, animated by the great Preston Blair, is lifted from Swing-Shift Cinderella (1945) and the multiple doorways gag is borrowed from another Avery cartoon, The Screwy Truant (1943). Even the idea of using a deadpan character to offset the more hyperactive, lust-fueled wolf was flexed earlier in the Droopy cartoon The Shooting of Dan McGoo (1945).

But hey, if all sequels / remakes were as amazing as this one, you wouldn’t hear me complaining. Little Rural Riding Hood takes all of these earlier elements and forms a comedy classic around them, ending up with the crown jewel of the Wolf & Red films and one of the all-time greatest cartoons ever made. In addition to Little Red Riding Hood, the film is a take-off of the tale of the Country Mouse and the Town Mouse, with a dopey hillbilly wolf coming to visit his distinguished and restrained cousin from the city, who takes him to a nightclub to ogle at the sexy Red Riding Hood performing.

The cartoon is a gag-filled work of furious brilliance from start to finish, opening up with a madcap chase between the hillbilly wolf and a homely countrified Red Riding Hood that contains more laughs than most feature-length comedies have in their entire runtimes. The hilarity of the film is in no small part due to the animation, which is in peak form. Avery had finally gotten his films to match his zany, flat and somewhat angular drawing style, and as a result, he could shatter, warp or disassemble his characters’ bodies with gleeful abandon. The scene of the wildly grinning country wolf tearing off his shirt and charging after Red in the nightclub is just about the funniest image imaginable.

The lust gags in these films are always tremendous, but the reactions seen here are so crazy that they make the jokes in Red Hot Riding Hood look like kid stuff. The two wolves (voiced by Pinto Colvig and Daws Butler) form a hilarious comedy team, and the short’s role-reversal ending is priceless. This is a rare film that makes you laugh no matter how many times you’ve seen it. Certainly few things are funnier than the simplicity of the phrase, “kissed a cow”.

LONG-HAIRED HARE

Directed by Chuck Jones; Warner Bros.

What’s Opera, Doc? (1957) is usually considered the greatest Bugs Bunny cartoon ever made, and you’ll hear no arguments from me, but what makes it so special is that it’s a twist on the series. It takes a typical Bugs and Elmer chase and plays it like a tragic opera, and our familiarity with the Looney Tunes is key to the humor. However, if you’re looking for the ultimate Bugs Bunny cartoon – that is, the one that shows the usual Bugs Bunny formula at its absolute peak – I would instantly direct you to another opera-themed cartoon, Long-Haired Hare, which remains one of Chuck Jones’ finest works.

In the film, opera singer Giovanni Jones attacks Bugs Bunny so he won’t be distracted while practicing his music, and Bugs retaliates by wrecking Giovanni’s performance at the Hollywood Bowl. Whereas Bugs seems eager to heckle someone in earlier films, this cartoon shows a more patient side to the rabbit. He is playing music, minding his own business, and he passively lets Giovanni’s first two attacks slide. He finally declares war after the third insult, and the build-up makes the smug opera singer’s comeuppance that much more delightful.

And believe me, this is some of the most brilliant revenge Bugs Bunny ever dished out. Bugs causes the entire Hollywood Bowl to vibrate by banging a mallet on the roof, squirts liquid alum in Giovanni’s mouth (making his head shrink, naturally) and blows Giovanni up with dynamite, all of which is hilarious not just because of the gags, but because we want to see Giovanni Jones’ ego taken down a few pegs (his judgmental glance at the audience as he walks out onstage is masterfully executed). Bugs is clearly enjoying this as well, although if our hero was presented as too angry or vengeful, the short would lose its good humor. Jones and Maltese wisely keep his revenge tactics good-natured and whimsical, allowing Bugs to dress up in drag as a tittering fangirl (“Frankie and Perry just aren’t in it! You’re my swooner, dreamboat, loverboy!”) and finally as Leopold Stokowski, easily the most well-known and respected conductor of the era (he is best known in animation circles for his involvement in Disney’s Fantasia).

And the Leopold disguise leads into perhaps the most brilliant climax in cartoon history. It’s funny enough that the entire orchestra starts chanting “Leopold” in hushed awe, simply because the rabbit showed up in a white wig and suit, but the sequence is just getting started. Bugs is clearly relishing playing the part of a lauded conductor, and Jones’ skills as a director are at their absolute greatest: the comedy timing is spot-on (the lack of music here is a nice touch), and the poses are ingenious. Bugs, after toying with Giovanni a bit, finally has him hold one powerful note for ages, causing the opera singer’s face to turn red and his collar to snap (Nicolai G. Shutorev provides the singing for the character, and he does an incredible job). Giovanni’s torment is deliciously presented, and the cartoonish impossibilities of the scene (Bugs’ glove remaining in the sky while he’s gone, Bugs receiving a package in the mail before his letter is even sent) make it all the funnier. At the end, when Bugs has destroyed Giovanni completely (along with the entire Hollywood Bowl), Jones gives the film a perfect ending. He doesn’t even need a clever final line, Bugs returning to his banjo is enough. This is subversive, anti-elitist entertainment at its best, and it’s all the proof anyone needs that Bugs Bunny is one of the strongest and most likable characters ever captured on film.

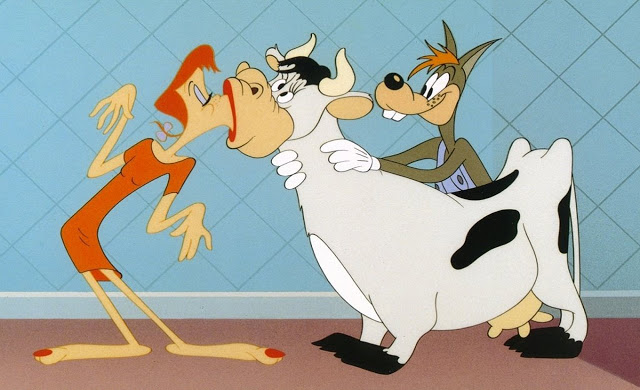

THE MAGIC FLUKE

Directed by John Hubley; UPA

In the 1930s, Disney set the standard for what animation could look like, and all of the other studios followed its lead. Of course, directors like Tex Avery and Bob Clampett provided a zany, exaggerated alternative to the Disney norm, but their characters were still fully-rounded and the movements were smooth. There were hints of a more stylized approach to animation in cartoons like The Dover Boys (1942) and the Baby Weems segment of the feature The Reluctant Dragon (1941), but it was really UPA that dramatically broke free of the Disney style, producing flat, graphic creations like Gerald McBoing-Boing (1950) and Rooty Toot Toot (1951) that showed a new approach to animation that had more in common with Picasso than Pinocchio.

This didn’t happen overnight, however, and when Columbia commissioned UPA to make some shorts with their starring characters the Fox and the Crow, the films only showed hints of the stylization that would hallmark their best-known work. Their first cartoon, John Hubley’s Robin Hoodlum (1948), has some strikingly flat layouts, but uses three-dimensional characters in the foreground that move with typical 1940s fluidity. The film shows a heavy Chuck Jones influence, likely due to involvement from Jones animators like Bob Cannon and Rudy Larriva (reportedly, animators from the Warner Bros. staff were even called in to pitch gags for the film). Still, it was unique enough to garner some attention, as well as an Academy Award nomination.

The Magic Fluke features a similar blend of old-school animation principles and barrier-breaking layouts, but it is a stronger cartoon and gives a greater sense of the direction UPA was heading towards. The story is more unique and interesting, the humor is sharper, the animation is even more bouncy and expressive and the stylized elements are more eye-catching. In the film, the Fox attempts to conduct an orchestra, but the Crow accidentally gives him a magic wand as a baton. This was an idea used to great effect in Tex Avery’s 1952 masterpiece Magical Maestro, but it originated here and Hubley makes great use of it. Hubley also puts a new spin on the Fox and the Crow’s personalities, which were typically that of a naive klutz and a street-wise swindler; although the depiction in this film has little in common with earlier appearances, it still works well.

Whereas the layouts in Robin Hoodlum were intriguing but easy to ignore, the stylization is an unquestionable element of The Magic Fluke’s success. The gorgeous backgrounds are insistently flat and sketchy, with some gleefully impossible uses of perspective. There’s one groundbreaking moment that features a shot of the audience applauding, and many of the faces are represented by circles or dabs of paint. Even the characters with distinguishing features are loosely drawn (color is applied sparingly, and much of it extends outside of the line-work), and the poses are static, making the clapping hands the only movement in the shot. There are also several sequences that involve jerky movements (the crowd in the jazz club towards the beginning, the Fox trying to keep the piccolo player from floating away), flat character designs (the men backstage who can’t find a baton for the Fox) and creative simplification (a splash of water represented by scribbles). This kind of stylization isn’t uncommon today, but it was unprecedented back in 1949.

The animation of the starring characters is less innovative, but still beautiful and highly entertaining. Hubley’s poses are strong, and the movements recall the appealing and squishy, loose-limbed animation Bob Cannon contributed to various cartoons by Chuck Jones (Odor-Able Kitty, Hare Tonic) and Tex Avery (Wags to Riches, Out-Foxed). Scenes like the Crow jamming out to a jazz rendition of Pennies From Heaven, or that painful moment where the Fox steps on the Crow’s head, couldn’t be more perfect. As much as I love the stylized animation in films like Gerald McBoing-Boing, one almost wishes it had taken UPA a little longer to find its niche so we could have more great-looking films like this one.

Another wish of mine is that UPA continued to pay as much attention to story and character as they do here. This is a fairly artsy and experimental short, but Hubley keeps the gags coming and the short has whimsical imagination to spare, setting up a simple concept (baton as magic wand) and wringing laughs out of that idea. Later UPA cartoons like Ballet Oop (1954) and Man on the Flying Trapeze (1954) are interesting to look at it, but are generally unfunny and hopelessly convoluted. John Hubley, on the other hand, understood how to deliver an entertaining and funny film with a well-told story while still showing off the stylized visuals, and that talent would eventually lead to classics like Rooty Toot Toot (1951), The Tender Game (1958) and Moonbird (1959). This cartoon isn’t too highbrow to get a laugh from singing rabbits with weird voices or a flag for PU popping out of the fox’s wand, and it’s all the better for it.

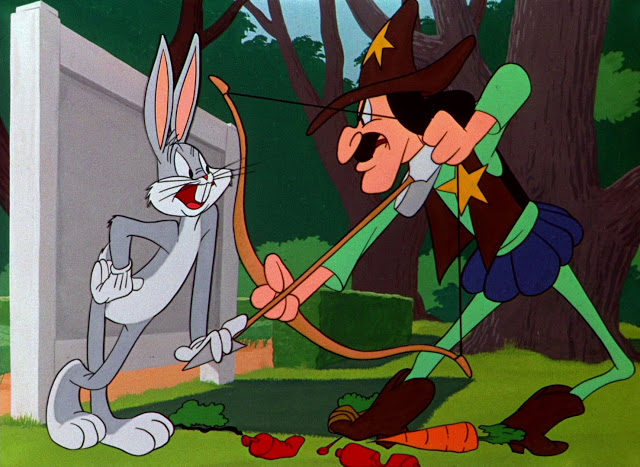

RABBIT HOOD

Directed by Chuck Jones; Warner Bros.

The legend of Robin Hood has proven to be a fertile source of ideas for animators. Of course there’s the Disney feature Robin Hood (1943), as well as Terrytoons’ Robin Hood (1933), Ub Iwerks’ Robin Hood Jr. (1934), Van Beuren’s Goode Knight (1934), Famous Studio’s Robin Hoodwinked (1948), UPA’s Robin Hoodlum (1948), MGM’s Robin Hoodwinked (1958) and Walter Lantz’s Robin Hoody Woody (1962), to name but a few. Director Chuck Jones took on the Robin Hood legend several times, first in one of his earliest films, Robin Hood Makes Good (1939), then again in the amusing Sniffles the Mouse cartoon The Unbearable Bear (1942) and later on in the screamingly hilarious Robin Hood Daffy (1958), one of his last truly great Warner Bros. cartoons.

But Rabbit Hood might be the greatest animated riff on the Robin Hood legend. In the film, Bugs Bunny attempts to steal a carrot from the king’s garden, but the Sheriff of Nottingham is on hand to stop the rabbit dead in his tracks. Jones and Maltese have a lot of fun with the setting here, from the regal-looking font in the opening credits to the Sheriff’s exaggerated Olde English (“Ods fish! The very air abounds in kings!”). As for Bugs, he is clearly an intruder on this period and setting, and initially he doesn’t even seem to be aware of where he is (“Rack? King’s carrots?”). One of the great pleasures of cartoons is that characters can not only appear in whatever situation or time period the film demands, but they don’t even have to fit in; this isn’t some zany middle ages twist on Bugs Bunny, it’s just regular old 20th Century American Bugs Bunny who somehow wandered into late-medieval period England.

Once again, Jones and Maltese show a fantastic grasp on Bugs’ character; it would be easy to make Bugs so impenetrably cool that he appears to have the whole cartoon figured out before it even starts, but here he’s clearly riffing and making things up as he goes along. That does nothing to diminish his coolness, however, and in fact strengthens it, adding a believability that makes his ability to always come out on top that much funnier and more impressive. And this film has some of Bugs’ best mischief ever: the sequence where Bugs repeatedly introduces the Sheriff to Little John is worthy of Abbott and Costello, and the bit where Bugs bakes a cake is one of the finest slapstick gags in film history. Also, I don’t think anyone has been swindled more completely by Bugs than the Sheriff here, who is somehow convinced to spend months building a house in the King’s Garden before figuring out that he was tricked (the moment of realization, as he looks around at what he’s been doing, is priceless). And then, of course, there’s the famous knighting sequence, which features such titles as Sir Loin of Beef, Essence of Myrrh and Milk of Magnesia. It’s a perfect demonstration of blending witty dialogue and cartoon violence.

In other words, everything about this cartoon is wonderful. The animation simply couldn’t be better, and every action and expression Bugs makes is both appealing and specific to his personality. While watching this cartoon again, I noticed one brilliant far-away shot where the Sheriff chases Bugs from beyond a lake. It’s quick, and Jones doesn’t draw attention to it, but it’s really beautiful. That, to me, is a great demonstration of the incredible work ethic these guys had in the Golden Age of Animation; Rabbit Hood was sold as disposable entertainment to be shown in front of a live-action feature, and yet the artists and animators worked tirelessly to make every aspect of the film as good as it could possibly be. The only explanation is that they were driven by their love of the art form, and it is for that reason that Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Porky Pig, etc. remain timeless.

Any comments or suggestions for this post? What are your favorite cartoons of 1949? Let me know in the comments below.

1 Comment