Well, folks, we’re nearing the end of the 1940s, but there’s still much cartoon goodness in store. 1948 was a strong year for animation: Warner Bros. and MGM were putting out some of their best films, Disney released the package feature Melody Time and UPA – after making political/advertising films throughout the ‘40s – finally scored a deal with Columbia to enter the theatrical cartoon field, releasing their first film Robin Hoodlum.

As far as new characters go, Warner Bros. debuted Hippety Hopper (introduced in Hop, Look and Listen) as well as Marvin the Martian (introduced in Haredevil Hare). Over at Famous Studios, the Little Lulu series was retired to make way for the Little Audrey series. Audrey had appeared as an extra in the 1947 film Santa’s Surprise, but 1948’s Butterscotch and Soda launched her career as a starring character.

As far as Academy Awards go, the nominees for 1948 included the Tom & Jerry short The Little Orphan (MGM), the Mickey & Pluto vehicle Mickey and the Seal (Disney), the Hubie & Bertie classic Mouse Wreckers (Warner Bros.), the Fox & Crow short Robin Hoodlum (UPA) and the Donald Duck cartoon Tea for Two Hundred (Disney), with Tom and Jerry being the eventual winners. Definitely some good ones there, but I have – criminally – not included any of them on this list (my love for Mouse Wreckers knows no bounds, but I already had three other Chuck Jones cartoons that I couldn’t cut). Also worth noting – The Woody Woodpecker Song, which debuted in the 1948 Walter Lantz cartoon Wet Blanket Policy, became the first and only song from an animated short to be nominated for Best Original Song.

Anyway, on this list you get a whole lot of Looney Tunes, along with a smattering of MGM and even a Terrytoon tossed in for good measure. Take a gander:

BACK ALLEY OPROAR

Directed by Friz Freleng; Warner Bros.

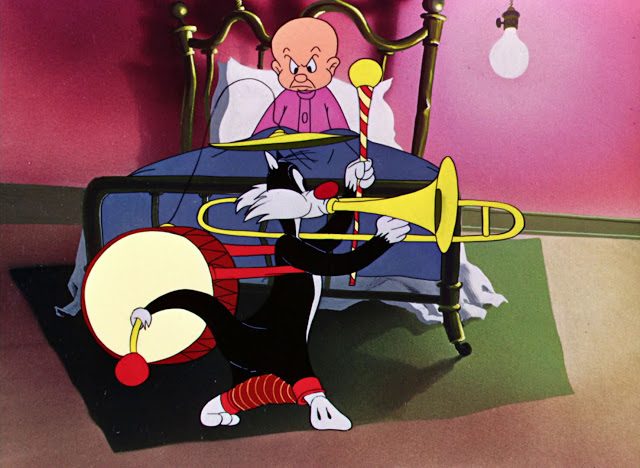

While Chuck Jones and Bob Clampett directed some of Warner’s finest music-related cartoons, Friz Freleng was really the music guy. He timed his cartoons out on musical bar sheets rather than the typical exposure sheets, and he directed more music-centered cartoons than anybody (Rhapsody in Rivets, Pigs in a Polka, Rhapsody Rabbit, The Three Little Bops, to name but a few). Back Alley Oproar is one of his all-time best, a cartoon bursting at the seams with joy and easily Sylvester’s finest performance (one of Mel Blanc’s, too; he’s gotta be the master at singing “funny”).

The film is actually a remake of Freleng’s 1941 cartoon Notes to You, which featured Porky Pig trying to get some sleep while a nameless cat kept him awake all night with his yowling. Back Alley Oproar vastly improved the concept, substituting Porky for Elmer Fudd and the anonymous cat for Sylvester. But Freleng was also a much better director by 1948, and the short is faster, funnier and better animated. Sylvester is a true performer here, belting out tunes like Some Sunday Morning, Moonlight Bay, You Never Know Where You’re Goin’ Till You Get There, etc., partially to get on Elmer’s nerves (why else would he stomp up and down Elmer’s stairway in giant boots while covering the Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2?) but mostly for the sheer joy of music. My personal favorite cover here is Sylvester’s Spike Jones-inspired Angel in Disguise, where he lights dynamite and tosses bricks on his head just for the sake of nailing the performance. What a trooper!

There’s too much good stuff to list here, but I’ve got to mention Elmer repeatedly slipping over greased stairs and walking on tacks (the timing and wacky animation couldn’t be better) and the bit with the unexpectedly operatic cat (even his stumbling off the roof is matched perfectly to the music). Those are big sequences, but the cartoon is also brilliant in all the little ways that separate a good director from a great one. Elmer opening a door that used to be a closet, only to run into a second door that says “surprise” is already a funny gag, but look at how well it’s pulled off: the timing is razor sharp, of course, and the wild drawings of Elmer’s body fluctuating from the impact of the blow are worth freeze-framing (you can’t see all of the great drawings, but you feel the impact). And to make it even more hilariously obnoxious, the second door is bright green and the word is misspelled as “surprize”. It’s little, but it makes the gag that much funnier. Similarly, Sylvester singing Elmer to sleep with a lullaby and then waking him up with a one-man-band is hilarious, but it’s Sylvester little kiss goodnight that makes it great. I also want to point out the way Sylvester tosses an anchor out of the boat prop he was using to perform Moonlight Bay, but if I keep this up I’ll be here all day.

Suffice to say, Back Alley Oproar is a really fun cartoon. It’s fun to watch and fun to listen to, and there’s a lot to enjoy even after seeing it dozens of times. Elmer might not be happy to find his afterlife filled with dozens of off-key Sylvesters singing Sextet from Lucia di Lammermoor, but this cartoon is some kind of comedy heaven.

BUCCANEER BUNNY

Directed by Friz Freleng; Warner Bros.

In this Friz Freleng classic, Yosemite Sam is a pirate captain who attempts to do away with Bugs Bunny because he knows where his treasure is buried. As with many of Freleng’s best cartoons of this period, the short is so full of classic sequences that any one of them would be the highlight of an average entry. Here you’ve got the treacherous parrot (“Awk! He’s in there! He’s in there!”), Sam trying to get Bugs off of the crow’s nest, Sam lifting up flaps on the ship to find cannons behind them, Bugs running through various doors, Bugs tossing matches into a basement full of gun powder, etc. And let’s not forget that wonderful gag where Sam swims all the way over to the ship to grab some oars so he can swim back and row his way over to the ship. I think we’ve all done something like that in our lives.

Yosemite Sam is a fully-defined character here, so it’s a little surprising to note that this is actually his second appearance, following 1945’s Hare Trigger (unless you count 1947’s Along Came Daffy, where two brothers that resemble Sam attempt to eat the titular duck). Sam is actually referred to in this film as “Sea-Goin’ Sam”, beginning a long-held tradition of giving the character humorous variations on his name as befits the setting, with examples like Shanghai Sam (Mutiny on the Bounty), Sam von Schamm (Bunker Hill Bunny), Chilkoot Sam (14 Carrot Rabbit), Riff Raff Sam (Sahara Hare), Sam, Duke of Yosemite (From Hare to Heir), etc. You have to love any character that gets so angry that he shatters his teeth from clenching them too tightly.

But, as usual, it’s Bugs Bunny who steals the show. The gags are strong enough that this film would be great even with a generic hero, but Bugs’ obvious glee in outsmarting Sam is a large part of the fun. For instance, the sequence with the flaps is already a masterful bit of impossible humor, but the way Bugs taunts Sam into lifting a flap again and again is what really sells it (“Yoo-hoo! Mr. Pi-rate!”). Still, my favorite sequence in the short, and one of the greatest demonstrations of what Bugs Bunny is all about, is the bit where Bugs repeatedly tosses matches into the powder room and Sam dashes off after them. The rabbit’s unflappable coolness as he puts both himself and Sam in mortal danger is classic Bugs: he knows Sam is going to rush after it, so why worry? Few things in this world are funnier to me than Sam attempting to feign levelheadedness as he plays chicken with Bugs (tossing a yo-yo, playing jacks, etc.) Even when it does blow up, it’s Sam’s panic that puts him in direct line of fire to the explosion, and Bugs’ smart-alecky response to the explosion couldn’t be more perfect. He has not even begun to fight, folks!

THE CAT THAT HATED PEOPLE

Directed by Tex Avery; MGM

In this excellent and memorable film, a cat with a voice like Jimmy Durante jumps on a rocket to the moon in order to get away from people. It’s a great premise, and Avery rises to the challenge, crafting a masterwork of great gags and hilarious drawings. The wacky scene on the moon is particularly fun, showing Tex Avery going full-tilt bonkers with absolutely nothing to hold him back. It’s Avery’s take on Bob Clampett’s immortal Porky in Wackyland (1938), and it’s an exhilarating burst of cartoon imagination. But Avery’s mastery of funny visuals even extends to the “normal” scenes – right off the bat, the cat’s grousing about humans is turned comic by the way the cat speaks out of the side of his mouth.

The short has a bit more of a plot than many Avery films; his more typical inclination was to set up a situation and riff gags off of it (examples: bird chases worm, rabbit keeps a dog awake all night, dog tries to stop a rooster from crowing, etc.). The Cat That Hated People is hardly a complicated narrative, but it has a bit of the hallowed beginning-middle-end structure that screenwriting classes today demand. That sort of thing isn’t necessary in cartoons, and it can sometimes actually hurt them; two of Avery’s other 1948 cartoons, What Price Fleadom and Little ‘Tinker, suffer in their attempts to mesh a Disney-style storyline with the typical Avery sight gags. But here Avery found a story that jived beautifully with his style, and the way he breezes through the tale while still cramming in the requisite wacky jokes is a really incredible achievement.

Although Tex Avery would’ve sneered at creating a preachy moralistic cartoon, this short actually has a mild point to it amidst all the jokes. While our lead character’s grievances with humans are generally cat-related, I think we can all relate to his being fed up with humanity and wishing we could blast off to another planet to be away from everybody. But, as the cartoon also reminds us, things could be a whole lot worse and we sometimes don’t appreciate how good we have it. That being said, the weirdsmobile creatures the cat encounters are so fun and creative that the moon actually looks like a fun place to be. I have a feeling that if a place like this really existed, Tex Avery would’ve been a frequent visitor.

DAFFY DILLY

Directed by Chuck Jones; Warner Bros.

Daffy Dilly marks one of Daffy Duck’s finest performances, and also one of his most underrated. In the film, Daffy is a struggling gag gift salesman who overhears that J.P. Cubish, the buzzsaw baron, is offering a million dollars to whoever can make him laugh before he kicks the bucket. Daffy attempts to get into his mansion to win the money, but a stuffy butler refuses to let him in. Writer Michael Maltese had already collaborated with Tedd Pierce on several assignments for director Chuck Jones (Little Orphan Airedale, Rabbit Punch, etc.), but this was one of his earliest as Jones’ sole writer, beginning a long, fruitful partnership. The cartoon shows signs of several future Jones classics (there’s a series of blackout gags that resemble the Road Runner series, which would begin the following year), but perhaps most importantly, the film really brings Daffy into focus, and displays the direction that Jones and Maltese would take the character in the future.

Jones directed some fine Daffy cartoons throughout the early part of his career, but he was clearly experimenting with what approach to take to the character. He never seemed to connect with the unmotivated lunatic Daffy (although he gave it a try in 1939’s Daffy Duck and the Dinosaur and 1942’s Conrad the Sailor), and had significantly more success by showing a mean-spirited side to Daffy’s heckling in My Favorite Duck (1942), To Duck or Not to Duck (1943) and Tom Turk and Daffy (1944). He then took a three-year break from Daffy, returning with 1947’s A Pest in the House, which portrayed the duck as an abrasive motor-mouth who doesn’t realize how obnoxious he is (it’s one of Jones’ few films where Daffy emerges unscathed). But it was in 1948, with the release of both Daffy Dilly and You Were Never Duckier, that Jones figured out a workable approach to the character: he’s still “daffy”, and still obnoxious, but greed and ego are added into the mix. In both films, Daffy is a conniving self-preservationist, eager to prove himself and doomed to failure.

It’s a winning combination, allowing us to both identify with Daffy’s debacles and laugh at them. In the opening scene, wonderfully animated by Lloyd Vaughn, Daffy desperately attempts to sell some gag gifts on the street, even going so far as to shock himself with a joy buzzer in order to make his point. But despite his failure to sell anything, Daffy is confident he can tickle the funny bone of a billionaire who hasn’t laughed in years. Daffy is in some serious denial here, a common trait among Jones characters; whether it’s Pepe Le Pew believing he is a lady killer, Charlie Dog’s insistence that he would be a lovable pet or Wile E. Coyote’s belief that he has a chance at catching the Road Runner, his characters often keep themselves going with a powerful dose of self-delusion. And Jones’ Daffy is perhaps the most extreme example of this, having convinced himself he’s a space explorer in Duck Dodgers in the 24th 1/2 Century, a western hero in Dripalong Daffy and a swashbuckling rogue in The Scarlet Pumpernickel, using bluster to disguise what seems to be a dim awareness that he doesn’t fit the part.

Here he believes he is a comedy genius, despite having no evidence to back that up. The irony is that even though he is portrayed as a flop comic, he comes across as one of the funniest characters to ever grace the animated screen. In one bit, Daffy is tricked into falling into the fountain, but instead of ending the gag with the splash, Daffy yells up at the butler to watch that first step (“it’s a dilly”). He then swims around humming Singin’ in the Bathtub, and remarks to us, “I was a bit dusty…” Daffy here demonstrates that he truly is a master comedian, making a funny situation funnier by finding multiple ways of riffing on it. The ending is also ingenious, nicely capping the film and commenting on the indignities we’re willing to face for a paycheck. And it’s here that Jones’ talent for expressions really shines: Daffy’s face as he is repeatedly smacked with pies couldn’t be more perfect in capturing his attempt to maintain a little dignity while enduring a humiliating situation. And best of all is a truly brilliant monologue where Daffy begins making wild accusations against the butler. The writing is outstanding, and the whole thing is masterfully brought to life by top animator Ken Harris. As Daffy himself points out, what’s Humphrey Bogart got that this guy hasn’t got?

THE FOGHORN LEGHORN

Directed by Robert McKimson; Warner Bros.

The Foghorn Leghorn was the third cartoon to star the southern rooster, following Walky Talky Hawky (1946) and Crowing Pains (1947), but it was the one that set the benchmark for future entries. In the short, Henery Hawk attempts to catch a chicken without knowing what one looks like. Foghorn attempts to prove that he is a chicken, but Henery is under the mistaken impression that the barnyard dog is the object of his desires.

Although many Looney Tunes characters were loosely inspired by radio / film personalities (Tweety was patterned after Red Skelton’s Mean Widdle Kid, Pepe Le Pew was a burlesque on Charles Boyer), Foghorn Leghorn is probably the closest thing to a direct imitation of a popular performer, similar to what Hanna & Barbera would later do with TV cartoons like Yogi Bear (inspired by Art Carney), Snagglepuss (inspired by Bert Lahr), Top Cat (inspired by Phil Silvers), etc. However, Foghorn Leghorn was actually a combination of two different radio personalities: a deaf Sheriff character (played by Jack Clifford) from the West Coast-only program Blue Monday Jamboree and Senator Claghorn (played by Kenny Delmar) from The Fred Allen Show. Foghorn has long been thought to be a straight impersonation of Claghorn, but recording of the first Foghorn cartoon, Walky Talky Hawky, predates Claghorn’s radio debut. In The Foghorn Leghorn, the Warner Bros. crew combined elements of the Sheriff’s personality (“I say…”) with some Claghorn-isms (“that’s a joke, son”, “…that is”). The result is a character that is probably funnier than either of his inspirations, and has certainly had a longer shelf life.

One reason Foghorn is such a great character is that he fits so well with McKimson’s directorial style. Not everyone likes seeing McKimson’s trademark huge mouths and wildly gesticulating arms on characters like Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck, but it works beautifully for a bombastic character like Foghorn. When the big rooster goes on one of his brilliant Warren Foster penned rants (“You’re built too low! The fast ones go over your head! You got a hole in your glove! I keep pitchin’ ‘em and you keep missin’ ‘em!”), it’s a perfect marriage of gut-busting dialogue and masterful animation. And all of his actions match his personality, from the way continually bops Henery’s dad with his stomach to the way he absently slaps the dog as he rants. This is fantastic acting.

Interestingly, Henery Hawk was intended to be the starring character in Foghorn’s initial appearances, and you’ll note that the titles on this short proudly proclaim “with Henery Hawk”. However, it was pretty clearly the loudmouthed schnook that made the biggest impact.

HAREDEVIL HARE

Directed by Chuck Jones; Warner Bros.

Bugs Bunny sure has gotten ripped off, hasn’t he? He discovered electricity (Yankee Doodle Bugs), won the Revolutionary War (Bunker Hill Bunny) and discovered America (Hare We Go), and yet he never receives any credit. In Haredevil Hare, you’ll find that Bugs Bunny was actually the first living creature to land on the moon, predating Neil Armstrong by over twenty years, and yet somehow history has forgotten.

Haredevil Hare marks one of Chuck Jones’ finest Bugs Bunny cartoons, and also a notable one considering it launched the beloved Looney Tunes star Marvin the Martian. Marvin, with his distinctive Roman helmet with a push-broom on top and ridiculous green skirt, was never actually given a name in the five original Warner Bros. cartoons he appeared in (he is referred to as Commander of Flying Saucer X-2 in The Hasty Hare), but was later assigned a name for merchandising purposes.

In this original film, Mel Blanc’s voice for the character is more nasally than it would be (it later evolved into an approximation of his voice for Claude Cat), but Marvin’s mild personality is fully intact. His intention is to blow up the earth (with the fabled Uranium PU-36 Explosive Space Modulator), but he goes about it as if it is the most casual thing in the world (er… universe). He’s a simple character, but an amusing one, and given the lack of facial expressions possible with his bowling ball head, Jones and his animators have to be very intelligent about acting choices to make it clear when Marvin is speaking. The animators also give him an appropriately offbeat little shuffle, which is nicely accompanied by robotic music provided by Carl Stalling.

Marvin is accompanied here by his green dog K-9, who reappeared only once in 1952’s The Hasty Hare. K-9 is as joyously absurd as his master, speaking in a stereotypical dumb guy voice and marching with his feet on backwards. Bugs uses the old switcheroo on K-9 here that he would later test out on Daffy, and this is one of the funniest uses of the device (I love Mel Blanc’s vocal delivery on Bugs’ mock-defeated comeback, “but I’m gonna tell my big brother… and he’ll fix you up, boy… yeah, yeah…”).

This film is as funny a slapstick comedy as any of the best Warner Bros. cartoons, but – as the strange designs of both Marvin and K-9 prove – it’s full of marvelously offbeat imagination. The layouts (by Robert Gribbroek) and backgrounds (by Pete Alvarado) are spectacular, giving a tangible reality to the settings, and Jones proves himself a master of staging during the incredible rocket launch sequence. The scene is exciting and dramatic, which makes Bugs flipping his lid all the funnier (poor Bugs doesn’t seem to have much luck with flying, having faced similar problems in 1943’s Falling Hare). And for that matter, Jones’ character poses are fantastic, most obviously in the scene (animated by Ben Washam) where Bugs starts twitching. Each expression is hilarious and unique, and you barely get time to register them (Jones masterfully snaps Bugs from one pose to the next in varying amounts of time so his jerks feel random rather than mechanical). These are some of the funniest expressions ever drawn, and each should be hanging in a museum.

But perhaps most importantly, Jones and Maltese show an in-depth understanding of Bugs Bunny’s character. Less confident cartoonists might have Bugs stick to being nonchalant for fear of losing his personality, but this short has the rabbit show panic and cowardice while still remaining 100% in-character. Particularly amusing is the way Bugs reacts to the news that Marvin intends to blow up the earth. He takes it pretty casually, tries to justify it to himself and even rather passively asks about it a second time before making a big reaction. And even then, Bugs is driven less by a Superman-style desire for justice and more by the fact that all the people he knows are on the earth. This is the work of people who understand a great character inside and out.

LUCKY DUCKY

Directed by Tex Avery; MGM

After giving birth to a new era of cartoon comedy in the 1937 cartoon Porky’s Duck Hunt, here we find Avery returning to the duck hunt, armed with everything he had learned about sight gags, comic timing and convention-breaking insanity in a little over a decade. The result is one of the flat-out funniest cartoons ever made; a laugh-a-second gagfest that serves as an anarchic assault on the senses.

In the film, two dog hunters (pantomime, canine variations on the big guy-little guy dynamic of Avery’s early George & Junior series) attempt to catch a wiseguy duckling. There isn’t much of a story, and the characters have nothing to them, but this is a Tex Avery cartoon we’re talking about and those things don’t come close to mattering. It’s all about the jokes, and there are some beauties here, from the duck conga line at the beginning to a bottle of Quick Gro (a subsidiary of Jumbo Gro, perhaps?) being used to create a tree for the hunter to run into. Particularly amusing is the way we see the duckling hatch from his egg, and then he immediately begins to heckle the hunters by doing an egg-shell striptease and drilling a hole in the boat. Avery characters are born with the innate desire to create slapstick mayhem, and they even have props right out of the womb.

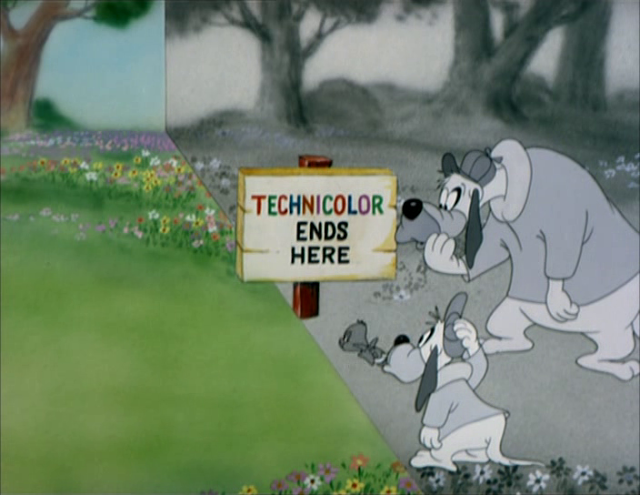

Everything in a Tex Avery cartoon exists just so it can be messed with, even the characters’ bodies: the two hunters are flattened like pancakes when they slam into a rock, the duckling opens up one of the dogs’ noses to pour pepper in it, the dumb dog reaches so far into his own mouth that the outline of his hand stretches out the back of his head, etc. There’s also a moment where the two dogs rush after the duckling, which didn’t even require a gag, but Avery creatively has each of the dogs’ individual body segments rush off at different speeds. Avery has no shame, and no limits: he might throw in an ingeniously impossible gag (such as that great one where the dog plugs up a hole and water comes shooting out of his ears) or he might indulge in a corny visual pun (like the school crossing joke). He’ll do anything for a laugh, and that’s what makes his films so spectacular.

The most celebrated sequence in the film is the “Technicolor Ends Here” bit, which perfectly summarizes Avery’s modus operandi to shatter any and all conventions of the form in which he was working. Brilliant and hilarious.

MOUSE CLEANING

Directed by William Hanna & Joseph Barbera; MGM

In this classic short, Mammy Two-Shoes gives Tom an ultimatum that if she comes back home to a mess, Tom is getting thrown out of the house. And – as you might imagine – Jerry takes full advantage of this precarious situation. It’s a premise that bares a strong resemblance to Tom and Jerry’s maiden voyage Puss Gets the Boot (1940), and charming as that earlier film is, Mouse Cleaning is a clear demonstration of how far Hanna and Barbera had come in the art of selling a gag.

This is slapstick comedy at its finest, with Tom’s increasing desperation providing fuel to the comic sparks. Look at the great acting the animators pull off in this one: when Tom sees a tomato stain on the wall, his upper body stretches back as he soaks in the gravity of what has just happened. Tom also has a perfect worried frown as he makes sure Jerry doesn’t drop any of the eggs he’s juggling. Jerry doesn’t get as much to do, acting-wise, but his delighted grin as he creates pandemonium tells you all you need to know.

Puss Gets the Boot had great performances, too, but Mouse Cleaning is that film on overdrive. The gags are bigger, bolder and more violent, and the timing is snappier. Hanna & Barbera are able to milk character comedy out of the situation just as they did in the 1940 cartoon, but they now have the added element of belly-laugh jokes and high-speed momentum that the series lacked in its early days. The drawings are also funnier than before, with the best example being that Tex Avery-inspired wild take when Tom sees paint on the wall: multiple sets of eyes bug out of Tom’s face while his jaw drops to the ground. Only perhaps the bees-in-the-mouth joke from Tee for Two (1945) can rival this bit as the funniest single image in a Tom & Jerry cartoon.

Note: This film, along with Casanova Cat (1951), have been left out of recent DVD/Blu-Ray releases of the Tom & Jerry cartoons. A pretty baffling decision, since the blackface gags seen in the films are actually less extreme than in many of the other Tom & Jerry cartoons (particularly His Mouse Friday, which is almost certainly Hanna & Barbera’s closest equivalent to a Censored 11 contender). For the record, the offending scene occurs towards the end, when Tom emerges from a pile of coal imitating actor Stepin Fetchit. One other racially-tinged joke occurs when Mammy Two-Shoes is returning home, and Scott Bradley intones an ominous rendition of her theme song Shortenin’ Bread, which I must admit makes me laugh.

THE POWER OF THOUGHT

Directed by Eddie Donnelly; Terrytoons

The Terrytoons Studio has a reputation as the most formulaic and workmanlike studio of the Golden Age of Animation, but it’s still a little surprising how few standouts there are in the studio’s history (at least until Gene Deitch took over in 1956). Some are better than others, certainly – the Heckle & Jeckle cartoons tend to be funnier than other series, and the operatic Mighty Mouse cartoons (Love’s Labor Won, Beauty on the Beach) are more entertaining than the straightforward entries (Port of Missing Mice, Deadend Cats) – but few Terrytoons dramatically rise above the others.

There are a handful of high-concept Gandy Goose cartoons – The Magic Pencil (1940), Post-War Inventions (1945) and Dingbat Land (1949) – that probably have the strongest claim as standouts. The Banker’s Daughter (1933) is notable as Terry’s first attempt at an opera parody, and is also one of the studio’s finest shorts. Catnip Capers (1940) is intriguingly surreal and dreamlike. Cat Happy (1950) and How to Relax (1953) are mini-masterpieces due to the amount of wacky Jim Tyer animation, and you can find shorts with bravura sequences from great animators like Bill Tytla (1932’s Bluebeard’s Brother, 1944‘s Mighty Mouse Meets Jekyll and Hyde Cat) and Carlo Vinci (1945‘s Krakatoa, 1945’s Gypsy Life), even if the films themselves are nothing special. I’ll also take this opportunity to admit my fondness for the obscure Golf Nuts (1930), which somehow transitions from generic golfing gags to a story of a mouse receiving eternal damnation.

Still, probably the closest thing to a Terrytoons classic is the 1948 Heckle & Jeckle cartoon The Power of Thought, which ventures into more cerebral territory than usual. In the film, Heckle and Jeckle come to the conclusion that they haven’t been taking advantage of the fact that they are cartoon characters, and so they begin to transform and distort the world around them while a dumb cop attempts to arrest them. It’s a great concept, and like all Terrytoons with great concepts (The Magic Pencil, Comic Book Land), the premise is more exciting than the execution (imagine what Tex Avery might’ve done with this). That being said, the short has a lot of creative ideas and the cartoonish zaniness of Heckle and Jeckle as characters make for a highly enjoyable short.

And then there’s the Jim Tyer animation, which is incredible. Tyer is almost certainly the wildest and most distinctive animator who ever lived. He paid no attention to keeping the characters on model, making sure drawings flowed smoothly into each other or even basic-level consistency (check out the way some of the broken dishes in this short blink on and off). But his off-the-wall lunacy and unstoppably creative animation is always a joy to behold, even when (as was usually the case) it was the sole redeeming quality of an otherwise routine cartoon. It’s a little hard to discern his style in the link below, due to poor quality, but he does the bulk of the work from the scene of the cop holding a bunch of dishes to the cop lighting his finger on fire.

It says a lot about the quality of animation in the Golden Age that even the laziest, most uninspired studio in the business was capable of producing an offbeat deconstruction of the animation medium like this one, and regularly featured the work of a totally original and brilliant talent like Tyer. Would that our current crop of bad cartoons were this good.

SCAREDY CAT

Directed by Chuck Jones; Warner Bros.

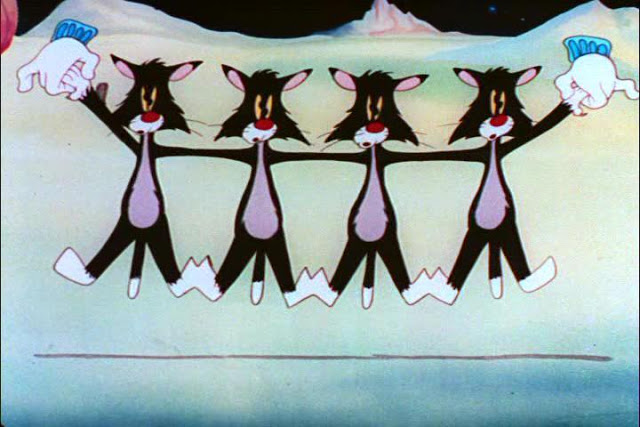

Sylvester might be the most versatile character in the Looney Tunes lineup. He is most often associated with creator Friz Freleng, who frequently had him chase characters like Tweety and Speedy Gonzales, and would also feature him in occasional one-shots like Mouse Mazurka (1949), Canned Feud (1951), A Mouse Divided (1953), etc. But other directors took a crack at the character as well, and no one played him quite the same way. Bob Clampett used him once as a gang leader to a bunch of cats in Kitty Kornered (1946), and Arthur Davis made him a dumb guy with a goofy voice in films like Doggone Cats (1947) and Catch as Cats Can (1947). Robert McKimson started a new series with the character where he mistook a kangaroo for a giant mouse, occasionally teaming him up with his easily-embarrassed son Sylvester Jr.

As for Chuck Jones, he turned Sylvester into a pantomime character and teamed him up with Porky Pig in a three-film series: Scaredy Cat (1948), Claws for Alarm (1954) and Jumpin’ Jupiter (1955). In each of the films, Sylvester plays the tightly-strung pet who notices something amiss, while Porky attempts to relax and is annoyed by Sylvester’s constant paranoia. This setup was milked to great effect in all three films, but Scaredy Cat makes the best use of the idea: in the film, Porky and Sylvester arrive at their new home, but an eerie group of mice attempt to murder Porky and Sylvester has to save him.

One of the film’s strengths is the range of emotions it evokes: the short is creepy, frustrating and hilarious all at once. The mice are so ominous, and Porky so bull-headed, that you can’t help but sympathize with Sylvester as he tries to alert Porky to the mansion’s dangers. And a big part of this audience identification comes from the amazing acting that Jones and his animators pull out of Sylvester: check out his look of self-pity as he attempts suicide, and his spot-on expression of guilt when his guardian angel calls him a coward. Sylvester’s pale white look of numb horror is genius, and that shot of Sylvester’s heart beating in his throat is one of the best expressions of fear ever in an animated cartoon.

Part of the film’s eeriness is how unusual the threat is. We’re used to the cartoon haunted house cliches (skeletons, bats, ghosts), but this short gives us something a little different and doesn’t do much to explain it. This is some weird cult of masked mice who execute cats and attempt to kill Porky for no apparent reason. The lack of answers about what exactly they are supposed to be, coupled with Porky’s ignorance to their existence, gives the short an uneasy feeling alongside all the laughs. And there are plenty, from the great slapstick gags involving falling anvils and bowling balls to Porky’s doomed attempts to form a coherent sentence (“I should’ve brought a cocker-span… a cocker-spani… a cocker-span… a dog”). The ending, which features an impersonation of Lou Lehr, comes a bit out of left-field, but otherwise this is a masterpiece from start to finish.

Any comments or suggestions for this post? What are your favorite cartoons of 1948? Let me know in the comments below.

1 Comment