|

| Photograph by Seth Kushner. Used with permission. Visit Graphic NYC |

The world of popular culture lost an icon today, with the passing of cartoonist/author/historian Jerry Robinson, who passed away at age 89.

FOG!’s Frankie Thirteen spoke extensively with Mr. Robinson in 2010 during the release of his biography, Jerry Robinson: Ambassador of Comics.

As a tribute, we’re running the entire interview after the jump.

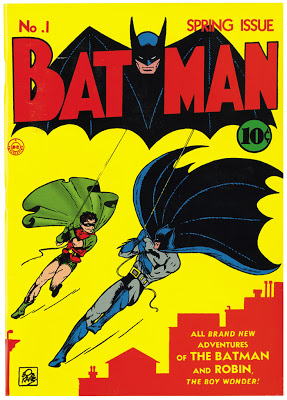

Writer/artist Jerry Robinson has been a significant presence in comics for more than seven decades, beginning with his work as an artist, then writer on Batman. During his time on the book, he would create two of the most enduring characters in popular culture, Robin the Boy Wonder, and the Joker. It would be easy to hang the rest of his career on that notable accomplishment, but Robinson could never be mistaken for complacent.

Over the course of his career, he has worked in every genre you can think of, from superheroes to war and westerns, to licensed properties such as the Green Hornet. He’s illustrated books and editorial cartoons, written manga, and become one of the foremost keepers of record in comics. To this day he’s kept busy: his autobiography, Jerry Robinson: Ambassador of Comics, was recently released by Abrams ComicArts; he expanded upon his seminal history, The Comics, which has been revised and is currently available from Dark Horse.

FOG: You’ve had such a career, but one of the things for which you’re best known is your work on Batman, from 1940-47.

JR: Well, I started in about ’39, until about ’47 or ’48.

FOG: At the start, you were enrolled at Syracuse. What were you planning to study?

JR: I was going to study journalism and creative writing, but I switched to Columbia when I met Bob Kane, just serendipitously in the country. He had just started Batman—the first issue was out—and he saw the drawings on the back of my jacket at the time, which I wore as a tennis jacket. I happened to be standing at the tennis court at this resort—we had both taken the week off. He had just finished the first issue of Batman, and I had just graduated high school. I was seventeen and I sold cream on a bicycle, hauling a truck around, a bicycle wagon. I had taken the week off to, as my mother put it, “fatten up,” so I could survive the first semester’s challenge. And so, when I met Bob, my application was still good at Columbia, so I switched from Syracuse to Columbia so I could come to New York, and started my classes and Batman almost at the same time.

FOG: So you were a full-time student with a pretty intensive job. How was it juggling that?

JR: Tough. (laughs) I was burning the candle at both ends, and I lasted about two and a half years before I had to end my classes and concentrate on Batman, which was so all-consuming. By that time, I saw that I liked the genre of narrative storytelling, and that I could write and draw together, so I didn’t feel I was giving up my writing career.

FOG: How was the comic book industry viewed by the general public at the time?

JR: Well, the general public were more or less indifferent. They didn’t know much about comic books. The kids related almost immediately, and that was the great impetus for the sale of comics. They grew out of the newspaper comic strip, which was an adult medium, as well as kids, but particularly for the kids. So the first comic books were really reprints of newspaper comic strips, starting in about 1934 and ’35. By ’38 and ’39, they had run out of suitable material in the comic strips, so they began to commission original work. And so, that’s what gave way to Superman in ’38 and Batman in ’39.

FOG: How was the dynamic between you, Bob Kane and Bill Finger at the time? I assume you worked pretty closely.

JR: Yes, very closely. Day and night. It was all-consuming.

We would draw Batman, eat Batman, sleep Batman, and think of ideas constantly. We would come up with new characters. It was a passion that we all shared. And it was exciting because it was a new medium, a new genre. There was no past, there was no precedent, so we should explore and experiment.

FOG: Around late 1939, 1940, there was some discussion about adding a boy sidekick character.

JR: Yeah, the following year. Bill Finger, the writer who created most of the characters and the whole mythos of Batman—there really should have been a co-creator credit, Kane and Finger—his idea was to add a kid to the strip.

He had been an avid reader, and there were all kinds of kids in children’s stories at the time, in hardcover books. He was extremely well-read in all sorts of literature, and I’m sure somewhere along the line he got the idea that you could extend the parameters of the story with the addition of a boy.

The next thing was to think up his name and costume, and after much discussion—names are very important in comics and all of literature, actually—we couldn’t hit on one, so I happened to think of Robin. I wanted a name that didn’t give the impression of being a superhero or having super powers, so Robin fit the bill.

I came to Robin because I was given a wonderful book of Robin Hood when I was about ten to twelve years old, which I still have in my library, The Tales of Robin Hood. They were illustrated by N.C. Wyeth, a very famous illustrator at the time, some in black and white, some in color. I pored over those drawings and read those stories so many times, so that’s how I came to think of Robin as a suitable name, and I designed his costume from my memory, which I knew so well. I didn’t have the book in New York, of N.C. Wyeth’s paintings of Robin Hood.

FOG: Aside of the name and look, how much more of Robin Hood did you try to work into Robin?

JR: Kind of the spirit of Robin Hood, of taking from the rich and feeding the poor and needy, and fit it in the whole concept of Batman as well as Robin. And Bill wrote the backstory of Robin being an orphan as was Batman, Bruce Wayne, whose parents were killed when he was young.

FOG: I don’t know how much you’ve kept up with the current Batman stories, but right now, Dick Grayson—Robin—is Batman. How do you feel about having a character who has endured and thrived to the point where he’s become the star?

JR: It’s an innovation I don’t know that I would have done myself, but you know, it’s lasted seven decades, so new writers and new artists take over and they have their own perception. But they kept the essential personas of the characters, and I think that’s what’s required. So I guess it’s somewhat of a tribute to the concepts that they have endured and can have as many interpretations as they’ve had over the years.

FOG: The Joker is the other really iconic character you created for the Batman mythos. I know you had a Joker card that inspired the basic look, but what else went into the characterization of the Joker?

JR: Batman was so popular in the first months of appearing in Detective, the publisher said, “It’s time to put out a new book, Batman #1, containing all Batman stories.” Overnight, we were confronted with doing five stories, one for Detective and four more for Batman #1.

So it was a big burden on Bill Finger as a writer, who was the best writer in the field at the time, but he wasn’t that prolific because he was such a fine craftsman.

So I volunteered to do one of the stories, as they all knew stories I’d already written for Columbia and other places. I’d written a lot of short stories, and most of them were satiric in nature and had humor. Of course, my offer was readily accepted by Bill and Bob because they were confronted with getting #1 out.

For my first story, I decided to have a supervillain, although we didn’t use that term in those days—a major villain to confront Batman and test him.

At the time, it was the thirties when the villains in real life were gangsters: Pretty Boy Floyd, Al Capone, John Dillinger. I wanted to do something more bizarre, more of its own quality than a work of fiction might have, to be on par with the Hunchback of Notre Dame. And I knew all great villains had some contradiction in their nature, like all great characters.

|

| From The Joker’s first appearance in Batman #1 |

I thought having a villain with a sense of humor would be different, and bizarre in a way. That was the impetus to do a story with a major villain I named the Joker, and once I thought of that, I thought of a Joker playing card for the visual. The Joker image has existed since the middle ages in one form or another as a clown or a jester, so it was a good image to pick up, to identify.

Once I did that, I knew it was going to be a great character, and it was immediately slated for the first story in Batman #1, so that was the beginning of it.

|

| The very first image EVER CREATED of the Joker! |

FOG: Superhero characters, especially Superman and Batman in those days, were darker, rougher and grittier. Over time, they lightened considerably, especially going into the ’50s. How did you feel about that transition?

JR: Well, I had left Batman in ’47 and I immediately plunged into other things, so I really didn’t follow it closely in those days. I worked with Stan Lee for ten years. I did all sorts of other stories ranging from crime, science fiction, adventure, war, and I wanted to something to break out of that one box on Batman. I thought I contributed enough over seven years to it. So I didn’t follow it.

|

| Robinson during his Bat days |

Then I got into book illustration. I illustrated some thirty books for major publishers of biographies, science, history, and then I did a newspaper strip, then became an editorial cartoonist. For thirty-two years, I did an editorial—political, social satire—one every day for six days of the week for thirty-two years. So I was heading towards other things while Batman went through many other artists and writers.

FOG: Your Cartoonists and Writers Syndicate represents a lot of political cartoonists. What drew your interest to political cartooning?

JR: When I was free to do whatever I wanted after leaving the comics, that was one of my goals, to be a political cartoonist. I’ve always been politically-minded. I always kept up with politics. I figure it ran in the family. My mother was a Democratic committeewoman when she was young, locally, in Trenton. I grew up with Frederick Roosevelt. He was very inspiring. So I got involved with politics. Even when I was doing Batman, I followed politics religiously.

In fact, one of my first characters on my own that I created and wrote was called London. I created that during the early days of World War II before we even got into the war. London was fighting the blitz, standing up against Hitler. His other identity was a radio announcer, so he was modeled after [Edward R.] Murrow, who was the great war correspondent of the time.

So politics was always part of my being, and I decided I wanted to devote all my time to it—well, I did other things while I was doing a political cartoon, but I did one every day for thirty-two years, so it was pretty all-absorbing. I became president of the American Editorial Cartoonists Association, and devoted a lot of my time to that. Then I founded the Cartoonists and Writers Syndicate in 1979 and gathered together the greatest political cartoonists and other graphic artists from around the world for my syndicate.

FOG: Your syndicate continues to operate and thrive today.

JR: You should see all the cartoons from around the world on the New York Times Syndicate website. The Times represents cartoon syndicates around the world, so we put up new cartoons from around the world every day. So your readers might like to see the best of foreign political opinion as well as—we put up American political cartoonists. We have the four of the top American cartoonists, Pulitzer Prize winners. And we also have caricatures, we have humor cartoons and other things as well.

FOG: That’s a lot of prestige under one banner.

JR: Yes it is. We have the equivalent of our top cartoonists here from countries abroad, every place from in Russia to South America.

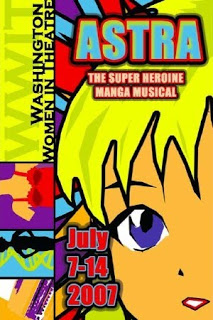

FOG: You also branched out into musical theater in a roundabout way. You created a character named Astra that was done as a Japanese manga. How was working in that style with your artist on that?

JR: Well, it was a co-creation. I co-created it with Sidra Cohn, who is a very fine writer and actress. It was first written as a musical, called Astra: A Comic Book Opera. It was in three acts and we wrote lyrics for some thirty songs. It was while we were in production that we had a show in Japan and we showed some of the original sketches for Astra to my Japanese publisher and they flew me over to work with a Japanese manga artist [Shojin Tanaka]. And so it was published in Japan, using the characters but not our story. Just kind of a general idea of the story, but not the actual thing. That was produced as a manga, mostly in a magazine then collected into a large manga. Later, it was translated by an American company into English, but with the Japanese story. So the American play was translated into manga and back into English. And finally it was produced in Washington, D.C. about two years ago, extracted from the opera.

FOG: With the Spider-Man musical headed to the stage, have you ever thought of bringing Astra back?

JR: Well, I’m involved in so many other things at the moment. I thought of it, but I haven’t had time to devote to it recently. Maybe I’ll get to it. I think it would make a very good film too. It’s a combination of science fiction, adventure and romance. A little bit of everything is in there, and political satire also.

FOG: Of course. Speaking of politics, you’ve demonstrated a sense of justice and respect for history, key qualities that led you to the creators’ rights arena back in the ’70s. You and [Batman and X-Men artist] Neal Adams had championed [Superman creators] Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster.

JR: They were close friends of mine in the old days, Siegel and Shuster. It was something very satisfying for me to be able to help them.

|

| Shuster, Neal Adams, Siegel and Robinson |

FOG: Did your personal experiences on Batman with the characters you created, as well as what happened to Bill Finger, fuel your efforts as well?

|

| Bill Finger by Jerry Robinson |

JR: Yes, since I felt the same things about Bill—he was very badly treated. He didn’t get co-authorship or money. In fact, he died broke. I knew Bill and his wife very well, and he had a young son. So that was almost as tragic as Siegel and Shuster. In fact, it was more so, because he never got his due. He was never acknowledged by Bob or the rest of the field until after his death. That was tragic.

I had the opportunity to do something, at least what I could do, after he was gone. You probably know it. I established the Bill Finger Award in his memory at the San Diego Comic-Con.

FOG: It’s moving, especially as a writer, because you never want to go through that where you spend all this time and effort, and it goes without acknowledgement.

JR: Oh yeah, it’s just tragic, you know, with his family and food at the table. It got down to that, as it did with Siegel and Shuster. They were the co-creators of some of the biggest properties of the 20th century, that made millions—billions, I should say, over the decades. And here they were, destitute. It was a tragedy of epic proportions.

FOG: But you were able, with Siegel and Shuster, to rectify that?

JR: As much as we could. Not entirely. But we preserved their dignity, got a livelihood to serve them the rest of their lives, and they were very proud of it. And most important, which was a personal thing to do, was to restore their name to the property. They had actually dropped their creator credits on everything, so we got it back onto all print and film [of Superman]. They were very grateful for that.

FOG: Do you feel today’s creators in the comics “mainstream” are getting that fair shake you were looking for?

JR: Well, it’s certainly much better. I can’t say it’s everything, but it’s all on an individual basis. But they do share, the newer ones. I don’t know what all their contracts are, but I do know their rights are better protected than they were before. There’s still a long way to go to achieve full creator rights that do exist in films and book publishing. That’s the most I can say about it.

FOG: You’ve been working a lot as well as an ambassador of comics—which is the title of your new book—and as a historian. As far as chronicling the history of comics, what is your favorite period in comics history?

JR: Well, I don’t know if it’s generally known, but I did this big history book back in the ’70s called The Comics: An Illustrated History of Comic Strip Art. It was a big coffee table book, and Dark Horse is republishing that in the spring. For that I wrote 20,000 new words, brought it up to date, changed a lot of information from before. The whole original book is being republished, but with all new color art, and I must say, Dark Horse is doing a magnificent job of reproduction. It’s going to be, I think, one of the most beautiful books on the history of comics every published. I’m very excited that project.

So that fits into your question about the history. I know the initial launching of comics—which I expanded on in this book with the Yellow Kid and his author, [artist/writer Richard] Outcault—was a fascinating period, and that launched the comics. And I show how it developed, as well as the European antecedents of the comics, the precursors. The ’30s and ’40s were a great period of creativity with a lot of writers and artists. Roy Crane was very influential; Milton Caniff, with Terry and the Pirates; [Alex] Raymond had beautiful art on Flash Gordon; and one of the supreme storytellers, Hal Foster with Prince Valiant.

Then came another whole genre of humor in sophisticated kids’ strips such as Peanuts, which was really groundbreaking. There was a strip before Peanuts called Skippy, which was very popular in the ’20s and ’30s. I did write a biography of that creator, Percy Crosby. That influenced a lot of the later kids’ strips, including Peanuts.

I love writing about the comics. I never tire of it. There’s always new facts about the characters. The creators are all geniuses in their particular genres.

FOG: One other question: whatever happened to that jacket?

JR: (Laughs) I wish I had it! I could retire on that alone, I think. Actually, I gave that to my—I had three nephews, sons of my eldest brother, who I was very close to, and I gave it to the oldest one at the time, who was probably about eight years old. As he outgrew it, he handed it to the next one who was two years younger, and then he handed it to next one. I think by that time, it must have been threadbare. Nobody knows what happened to it, finally. The family got a lot of use out of it.

The Comics: An Illustrated History of Comic Strip Art by Jerry Robinson

are available wherever books are sold.