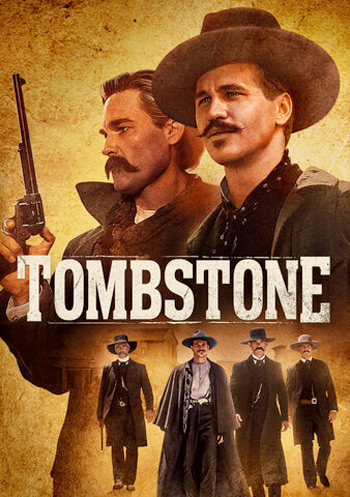

Disney / Buena Vista

Of the Western revival in American cinema in the 1990’s, two films primarily remain in the public consciousness: Clint Eastwood’s 1992 elegy, Unforgiven and the subject of this review: 1993’s Tombstone.

The two could not be more different in tone: Unforgiven is a somber, meditative, slow burn on the existential implications of Western legends and how it celebrates violence.

Tombstone unabashedly revels in Western archetypes and presents a clear cut showdown between good and evil.

Unforgiven feels like the final word on Westerns, and one comes away from Tombstone wondering why they ever stopped being made.

Tombstone began life as one of those “perfect scripts” that get a story in Variety when they’re snatched up for millions.

In Tombstone’s case, Disney was so impressed by veteran screenwriter Kevin Jarre’s script, that they amassed a dream team cast of tough guy actors to fill out the large ensemble (including cameos from legends like Robert Mitchum and Charlton Heston), and offered the director’s chair to Kevin Jarre.

Jarre directed for about a week, ran way over time and budget and was replaced by veteran director George P. Cosmatos (Rambo: First Blood Part II) with the film at least partially “ghost directed” by star Kurt Russell.

Kurt Russell plays legendary former Dodge City marshal Wyatt Earp who arrives in the titular Arizona silver town in 1880 with his brothers Virgil and Morgan (Sam Elliott and Bill Paxton) and their wives to win their fortune in the thriving boom town.

What they don’t expect is to find the town controlled by the boss of the bloodthirsty “Cowboy” gang “Curly Bill” Brocius (Powers Boothe) and his second in command Johnny Ringo (Michael Biehn). Soon, the Earps and Wyatt’s best friend Doc Holliday (Val Kilmer in what is probably his all time greatest role) are drawn into a feud with the Cowboy gang at the O.K. Corral that escalates until Wyatt once more dons his Marshal’s badge and rides out to smash the gang once and for all.

Tombstone condenses an enormous amount of history into 130 minutes by drawing caricatures based on mythic Western archetypes and leaving the real texture and dimension to Wyatt Earp, Doc Holliday, and Johnny Ringo. It is therefore able to marshal (pun intended) an enormous ensemble cast and give a startling number of them their moment to shine because the film trusts the audience to see the character and read their expectations into them.

Billy Zane, Jason Priestly, Billy Bob Thorton, Dana Wheeler-Nicholson, and Jon Tenney all come to mind as very talented character actors who get a moment in Tombstone that is indelible in the film and then fade out quickly. It’s truly remarkable how the script juggles so many supporting players.

Michael Biehn, Stephen Lang and Powers Boothe deserve to be singled out in particular for their villainous performances. Boothe is actively terrifying as the sadistic “Curly Bill” who is presented here as an opium addicted psychopath who is dangerous at any moment. Stephen Lang is great as Ike Clanton who alternates between insane bravado and then almost pitiable cowardice as soon as he’s threatened. Best of all is Michael Biehn as Johnny Ringo, the mirror to Doc Holliday whose ruthlessness is made all the more chilling by his obvious self-awareness of what a soulless monster he’s become.

That said, this film belongs to Kurt Russell and Val Kilmer.

The emotional throughline of the film is the friendship between Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday and the action of the film serves as a rising tide of urgency in their search for meaning at this crossroads of their lives. Earp believes himself to be a cold pragmatist, immune to sentimentality and searching for his fortune while Holliday fancies himself a touch of class in a cursed, lawless, amoral land.

The battle between the Earps and the Cowboys sets them irrevocably towards what matters most: Earp needs to provide order and serve the community, to avenge friends and family, to find meaningful love and live on his own terms. Doc Holliday, on the other hand, realizes that what he’s really after is death with honor and meaning. The search for life and death invigorates one another, and the real life history of Tombstone (which was much more ethically unclear than the film suggests) becomes a mythic structure for our dual protagonists in the same way the French Revolution is used in Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities.

The myth deepens with every rewatch. Tombstone will remain evergreen with every rewatch, as a great, populist, film overlaying a story about life and death and friendship that will never grow old.

Extras include Making of Featurette and Director’s Storyboards.

Recommended.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login