- The Simpsons’ “22 Short Films About Springfield” isn’t actually a parody of François Girard’s 1993 genre-crossing film about the life of Canadian pianist Glenn Gould. There are zero references to steamed hams in Thirty-Two Short Films About Glenn Gould.

- The film has just become part of the Criterion Collection, which is a good occasion to celebrate it here.

- Girard wanted to make a biography of Gould, but he had a hard time finding a narrative structure. Should it be a formal documentary? A biopic? How do you make a movie about a musician who wouldn’t give concerts or even talk about his music? Finally he read something Gould wrote about the thirty-two “thematically linked but independent-minded” pieces in Bach’s Goldberg Variations. This inspired Gerard to create a series of thematically linked, mostly chronological, but stylistically independent pieces that capture many facets of this sparkling, eccentric, and yet impossible-to-pin-down performer.

- Glenn Gould contained multitudes. As a child, he memorized his multiplication tables up to six figures. He often said that if he couldn’t play the piano, he would have become a mathematician. As one of the short films recounts, he used that facilty to make a killing on the stock market: his broker said that if he ever got tired of the piano, he should become a stockbroker. His doctor said that Gould would either become a great musician or a great physician. Gould once told an interviewer that he didn’t much like the sound of piano music.

- The interviewer Gould said this to was Glenn Gould. Interviewing himself for publication is just one of many eccentric habits that the film dramatizes. Another is his decision in 1964, controversial at the time, to stop playing public concerts and devote himself entirely to making music inside the recording studio. He got there three years before the Beatles.

- Gould said he wanted to stop performing because there were too many factors out of his control and he wanted the listening experience to be perfect. And yet this same person refused to edit out the sound of his chair squeaking or his own humming along with the melody.

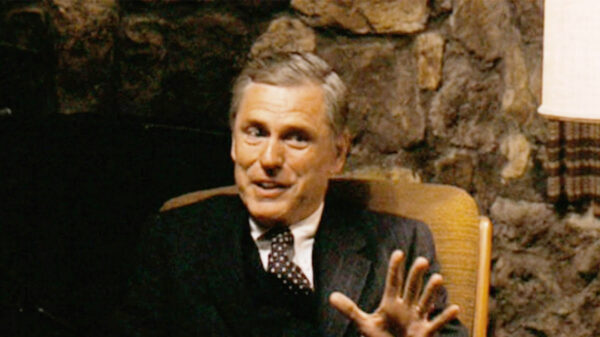

- Speaking of perfection, Glenn Gould is flawlessly played by Colm Feore, a Canadian actor whom Girard discovered playing Mercutio in a production of Romeo & Juliet. Mercutio, Romeo’s friend, is known for a prickly but playful personality and he dies too young. We spend nearly the entire movie one-on-one with Gould, so I’m glad Feore has the job. He uses his erudite yet curiously gentle voice to great effect in his interpretation of Gould, who was also prickly and playful and died too young.

- During his life, Gould’s style was often dismissed as “jazzy” and “unemotional.” Better to say that he was precise. He had the ability to separate notes in such a way that you could hear each melodic line independently without losing your sense of the overall structure. This made him one his generation’s pre-eminent interpreters of Johann Sebastian Bach, who is also praised for his mathematical precision and occasional playfulness.

- Gould wasn’t just a pianist. He composed original pieces, interviewed people from all walks of life for Canadian radio, and wrote—better say composed—an audio collage known as The Idea of North, in which he blended the speaking voices of various people who lived above the Arctic Circle. He liked to ask people questions that had nothing to do with their alleged area of expertise—for example, interviewing a housewife about the art market or the conductor Leopold Stokowski about the possibility of interplanetary travel—all to get more interesting answers.

- As Thirty-Two Short Films About Glenn Gould relates, conversation was nearly as important to him as music. On late-night drives he would pull over his Lincoln Continental to call people from public payphones. He would randomly phone friends at all hours, and occasionally they’d fall asleep while he was talking to them.

- In spite of his eagerness to talk, he remained an isolated and highly introverted person—reflected in his distaste for interviews, his preference for isolated retreats, and his inability to form lasting romantic attachments.

- Gould’s hypochondria is either the neurotic manifestation of his introversion or a necessary consequence of it. Even in warm weather he layered himself in sweaters, scarves, and gloves like a cartoon hobo. One of the thirty-two short films is devoted entirely to a recitation of all the medications he was taking and their possible side effects.

- Maybe he wasn’t a hypochondriac. He died of a stroke at the age of fifty.

- Girard’s method for constructing Thirty-Two Short Films About Glenn Gould was one that Gould might have appreciated. He started by listening to Gould’s recordings—all of them, amounting to hundreds of hours. Then, on repeated listenings, he’d boil the list down to sixteen hours, then four, and finally to roughly two hours of Gould pieces that captured the spirit of the story he wanted to tell. Rather than writing the films and then finding appropriate music, Girard wrote and visually conceived each piece around the music. The movie is essentially variations on a theme, a musical structure that Bach raised to an art form and that Gould interpreted wondrously.

- Each piece has its own unique style. Parts of it dramatize key moments in Gould’s life (such as the night he used an autograph for a stagehand to announce his retirement from public concerts). Parts of it are focused on a topic: “Questions With No Answers” consists of people failing to get Gould to talk about himself (the last and saddest is a woman asking, “Why won’t you answer my calls?”). Some of the pieces are interviews with people who knew Gould—his manager, the violinist Yehudi Menuhin, the cousin he spoke to right before his death. One them is an excerpt of experimental animator Norman McLaren’s interpretation of Gould playing a Bach fugue. The effect is that of a jigsaw puzzle. The pieces don’t always fit.

- Not fitting together appears to be the point.

- There is a conventional structure to all musical biopics that Thirty-Two Short Films About Glenn Gould refuses to follow. This can be termed the promise-destruction-redemption arc. A young musician proves him- or herself naturally good at music and enjoys early success (promise). At the height of their career, the demons of childhood combine with the pressures of fame to drive the musician into drugs or other habits that threaten to block out the music (destruction). Finally, the support of family, the adoration of fans, and the love of music conspire to put the musician back on a positive track (redemption). Exhibits for the prosecution: Walk the Line, Ray, Rocket Man, Bohemian Rhapsody, Judy, I Saw The Light, The Doors, Immortal Beloved, Amadeus, Coal Miner’s Daughter.

- Gould was absolutely brilliant, but it’s unclear whether this was nature or nurture. He was a well-known kook and did take a lot of drugs, and while he did occasionally fail to show up for concerts, he never did a “freak out in front of the fans” like Jim Morrison or Johnny Cash. He may have appreciated his fans but he did not like performing for them. He would have been a terrible subject for a conventional biopic, so it’s lucky that Girard got to him first.

- That part about the fans is probably unfair. One of the best of the thirty-two films, “Hamburg,” shows him stuck in his hotel room, afflicted by a cold that’s forced him to cancel yet another concert. A package arrives for him, followed by a chambermaid who needs him to leave so she can change his sheets. Instead, he guides her to a chair that he’s set at a precise distance from the portable record player, all so she can listen to what’s in the package—a recording of him playing Beethoven’s Sonata No. 13 in E-flat major. So it is a concert of a sort, except that it’s just her and he’s not actually playing anything. He starts off the segment refusing to perform, and yet it’s vitally important that the maid listens closely, and her reaction genuinely matters to him.

- The short films defy the fundamental precept of biography, that to understand the life is to understand the man. There is no single epiphany where we say, “Ah, now that is who he is.” The short films share essential truths, but they don’t engage each other.

- Nor does the film attempt to dumb down the creative process for us. You know that moment in Ray when Ray Charles starts noodling around and suddenly he’s created “I Believe to My Soul”? Or that moment in Walk The Line where Johnny steps up the tempo and starts playing “Folsom Prison Blues”? Or that moment where Mozart sits down at the piano and whips up his most famous number from The Marriage of Figaro? Or the—okay, you get the point. You will not find a moment like that in Thirty-Two Short Films About Glenn Gould.

- Every one of the thirty-two films bears close attention, but a few stand out.

- “Truck Stop” shows Gould at a local diner—he hated cooking—all so he could drink in the conversations swirling all around him. Weaving in and out of the audioscape is Petula Clark singing “Downtown.” He frequently praised Clark’s musical genius. Nobody knows if he was serious.

- “Personal Ad” has him reading aloud one of the best letters seeking romance (or, as he terms them, “moth flights”) I’ve ever heard—then deciding not to send it.

- “A Letter” is simply Colm Feore narrating a letter Gould wrote to someone, possibly his onetime lover Cornelia Foss, about his loneliness, his illness, his desire for connection—and his inability to let himself have any of these things.

- “Motel Wawa” has him describing his beliefs in extrasensory perception and the afterlife, related though a memory of him and his mother having the exact same dream on the same night.

- “Diary of a Day” is just a list of his blood-pressure readings, which he did obsessively: fear of death was never far from his thoughts.

- “Forty-nine” reveals Gould’s morbid fascination with numbers. Throughout his life, he insisted that he would die at the age of forty-nine. He was only off by a year.

- Thirty-Two Short Films About Glenn Gould is a celebration, not a dissection. By turns it’s elegaic, mysterious, moody, light, even hilarious (before a concert, his manager keeps telling Gould “don’t read this” while continuing to explain what’s in the document he doesn’t want Gould to read). The effect isn’t like watching a man’s life unfold. It’s like you already know him well and you’re just seeing him in action. Structurally, it feels like music. You know you’ve been on a journey, but you don’t know what happened on that journey. All you know is how the journey felt.

- It’s difficult to say what kind of legacy the film has left. Todd Haynes cited Girard’s film as an influence on I’m Not There, in which six different actors are used to capture the conflicting sides of Bob Dylan. American Splendor mixes documentary and fiction, and The End of the Tour relies on transcripts to take us into the mind of David Foster Wallace. These films share Girard’s mission to explore enigmatic people, but none of them are as formally daring. I’m not sure you could replicate Girard’s technique without it becoming a parody or an homage. It is a genre unto itself.

- Movies that approach it in structure are hard to find. Robert Altman’s Short Cuts, maybe or Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams, in which fragmentary episodes combine to form an experience that’s thematic, not narrative. Maybe even Richard Linklater’s Slacker, though I’ve yet to be convinced that Slacker even has a theme. Perhaps the thing I like best about Thirty-Two Short Films About Glenn Gould is that there is no expectation for any other film to follow in its footsteps. It is that rarest of all films, in which form and content are one and the same.

- A coda: Glenn Gould’s music has left our solar system. On Voyager I and II’s famous gold discs is a Bach fugue played by Gould. It will never return to earth.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login