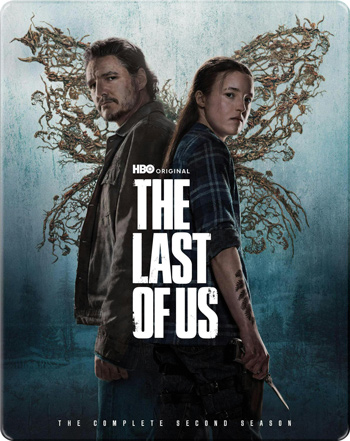

Warner Bros.

A friend once explained the video game The Last of Us to me as “Super Mario World, except the mushrooms bite you.”

I was pleased to discover that the Naughty Dog game and its HBO adaptation are so much more than this Yakov Smirnoff description. The game does for the cut scene what Hamlet does for soliloquys. The Season 1 finale is the Trolley Problem on an apocalyptic scale: is the survival of countless strangers worth more than the life of someone you love?

For the record: no, you don’t make antidotes by killing the only person with a natural immunity. You try to keep them alive so you can keep taking samples. But we’ll let the game’s creators have that one. The Last of Us isn’t about science or mushroom people, but what it takes to survive without losing your soul.

The first season explored this theme with heavyweight force—most notably in “Long, Long Time,” aka the Bill and Frank episode, where a paranoid survivalist (Nick Offerman) learns to open his heart to a total stranger and ends up sharing his fate. As George Orwell put it, when death is inevitable, the job of living is not so much to stay alive but to stay human. And the price of staying human is serious pain.

Grizzled smuggler Joel (Pedro Pascal) has lived for so long precisely because he doesn’t let anyone get close enough to hurt him. When he’s charged with protecting Ellie (Bella Ramsey), the one person who can’t be mutated into a mindless Cordyceps, it awakens a fierce protective instinct: she’s roughly the same age as the daughter he lost the night the infection broke out.

When he finds out his own people want to remove Ellie’s brain to extract a cure, Joel goes on a death-rampage where he kills eighteen members of the liberation army known as the Fireflies—including the only scientist who might have found a cure. By saving Ellie, he seals both the planet’s fate and his own doom. Someone’s going to want revenge for that.

Someone gets it. At this writing it’s no spoiler to say that Joel is brutally murdered in the second episode by Abby (Last Man Standing’s Kaitlyn Dever), daughter of the brain surgeon Joel killed. His death scene cuts to the bone, not the least because it’s his desire to protect others that lures him into Abby’s trap.

Just as Abby promised, it takes a very long time for Joel to die—and Ellie is forced to watch. With her is new love Dina (Isabela Merced), who joins Ellie on a quest for revenge. This is the game mission of The Last of Us sequel and the story arc of the show’s second season.

It takes a long, long time to recover from Joel’s death, and by the time we do it’s clear we are in very different territory from Season 1.

The mutant Cordyceps and the quasi-fascist Fedra have largely been sidelined. Apart from a grueling set-piece invasion of Jackson Hole, the Cordyceps are mostly secondary villains (there are signs that some of the runners are getting smarter) while the Fedras have lost ground to a violent new faction, the Wolves. Abby and the remnants of the Fireflies have joined the Wolves and now battle for territory with an apocalyptic cult aptly known as the Scars.

This is a war with many victims and no heroes: while the Scars appear at first to be the oppressed minority, they’re also fond of baroque executions in the name of their prophetess. The Gaza War and January 6 have just entered the chat.

All of this should give The Last of Us a bigger canvas to paint on, but it mainly fuels distraction. What exactly does this war have to do with Ellie’s revenge? If both sides are evil, why does it matter who wins?

Since humanity’s survival is presumably off the table, the current storyline is mostly backward-looking.

There are lots of nice little callbacks—Ellie recovering Joel’s broken watch and leaving his beloved coffee beans on his grave—but these are the gentler burdens of memory. Season 1 ended with Joel telling Ellie that the Fedra killed the Fireflies.

In Season 2, that lie is exposed and Joel suffers its consequences. The casualties aren’t just his life but Ellie’s naïve faith in him. The harder she pursues her revenge, the more we’re meant to ask whether his actions made him worth avenging.

It’s on this point that Season 2 is unconvincing.

In theory, yes, Joel is a worse person than the people who killed him—and yes, Abby is entitled to her revenge. Or so they keep telling us. But the audience already forgave Joel in Season 1, for the same reasons Joel chose his path: we know Ellie; we don’t know the people he killed. We’re supposed to condemn him, but we can’t. The show has done too good a job of making us see the world through his eyes.

Many reviewers agree that Season 2 suffers from the loss of Joel as a protagonist.

They’re not wrong. Dina is a good partner to Ellie—and, since she’s now pregnant by her duty-bound ex-boyfriend Jesse (Young Mazino), she holds a potentially new source of hope for humanity—but she’s no Joel. Pedro Pascal’s battle-scarred vulnerability was the perfect counterpoint to Bella Ramsey’s steely determination. Without him to body-block for her, Ellie comes off as reckless, even frenzied.

She’s been headed this way for a while.

One of the big leaps forward in the video game was when players shifted to Ellie’s point of view. We discovered that she’s good at killing when she has to, which is fortunate because in this season a lot of people need killing. Season 2 Ellie is weak on emotional uplift. Never thought I’d say it, but her recitations from No Pun Intended are sorely missed.

The showrunners clearly agree, since they bring Joel back for an entire episode of flashbacks, “The Price,” based on one of the game’s most-loved narrative sequences. Told across three of Ellie’s birthdays, it fills the gaps between seasons as Joel tries, with increasing desperation, to keep kindling the light in Ellie’s eyes.

On her sixteenth birthday, all it takes to delight her is a new guitar and Joel’s off-key rendition of Pearl Jam’s “Future Days.” Lyrics like “If I ever were to lose you / I’d surely lose myself” hit the nail fairly hard: he’s built his entire world around Ellie.

For her seventeenth, Joel goes all-out by taking Ellie to the Wyoming Natural History Museum, where she can climb on a T-Rex sculpture and imagine a lunar launch in the actual Apollo 15 space capsule. This is Season 2’s emotional high water mark, the only scene that truly aspires to the brilliance of Season 1. Ellie experiences both the doom of the dinosaurs and the idealistic hopes of Project Apollo.

This is also the last time Joel will get to see her as a child.

By her eighteenth, she’s got burn scars and tattoos to cover her Cordyceps bite marks, she’s started to fool around with girls, and she’s beginning to see Joel’s darker side. After an older man named Eugene is bitten, Joel promises to lead him home so he can say goodbye to his wife Gail (played with world-weary loopiness by the great Catherine O’Hara).

The moment Ellie’s back is turned, he shoots Eugene in the head.

It’s a gutpunch moment, all the more so because this is what finally rips the scales from Ellie’s eyes. All Joel wanted was to protect Ellie—not just from the bad guys, but from the truth about himself. When her illusions are destroyed, her first move is to tell Gail what really happened.

“I don’t think I can forgive you,” Ellie tells him after months of struggling with her disillusionment. “But I’d like to try.” This crystalizes everything we love about her and Joel. By rescuing her from the scientists, he’s forced her to bear responsibility for humanity’s doom and any point her life might have had. But ultimately love wins out.

At its best, The Last of Us is epic tragedy on the scale of Homer’s Iliad.

Just as man-slaughtering Achilles’s quest for vengeance nearly dooms the Greek cause, the Trojan prince Hector embodies duty to his people. Here, Joel and Ellie stand on the slaughtering side, while characters like Jesse and Joel’s brother Tommy (Gabriel Luna) are the Hectors of Jackson Hole. Ellie has a choice: she can embrace her responsibilities to Dina and her unborn child, return home and try to preserve what’s left of human society. Or she can go all-in for revenge.

In the final episode of Season 2, Ellie makes her choice. That’s the cliffhanger we end on, and it’s also where we walk away from Ellie. If Season 3 sticks with the storyline of The Last of Us Part II, we’re going to be seeing a lot more of Abby.

I’m kind of wishing we wouldn’t. Despite everything the showrunners do to make The Last of Us work as television, it still has the feel of a first-person shooter. Every scene plays the same: pick up these weapons and fight your way through these bad guys on your way to this goal.

Every so often, we shift to another character’s point of view, which is the game’s way of broadening our perspective.

In a first-person shooter, this is effective storytelling—screw that, it’s genius—but in a television series the shifts are jarring. In a game, when you play as Abby, you essentially become Abby. I don’t mind watching Abby but I don’t want to be her. Abby killed a character I love, so she can go to hell.

And yes, I realize that’s the whole point of The Last of Us. As with Melanie Lynskey’s Season 1 portrayal of rebel leader Kathleen, it’s easy to judge characters until we walk in their shoes. But just because someone has a point of view doesn’t mean they have a point. Again: Abby killed Joel.

It’s hard to watch The Last of Us without being reminded of another HBO series that featured Bella Ramsey and Pedro Pascal, Game of Thrones. Before it went all dim and kerflooey, GoT worked by letting us choose our favorites, only to break our hearts when our favorites die.

That’s also how things work in The Last of Us. Sometimes.

By forcing us into the perspective of one character or another, the writers are essentially choosing our favorites for us. They’d have served us better by letting us come to our own conclusions about Joel, Ellie, and Abby.

Games work by creating the illusion of choice.

You might think you’re guiding the action, but really you’re being funneled down a preset path. Narrative can’t give us that, but it can give us something much more powerful: the freedom to decide how we feel about what we’re seeing.

If Season 2 of The Last of Us had done more of that, it would give us a reason to hang on for Season 3. As it is, we’re mainly just hanging around waiting to see what happens next.

It gives us suspense, but what we really need is something that’s in short supply nowadays: a reason to hope.

Extras include “making of” featurettes, as well as a significant number of other featurettes.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login