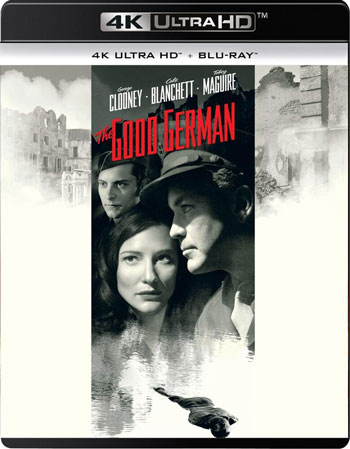

Warner Bros

Back in the studio days, there was a contractual requirement that if your movie was shot in Technicolor, there had to be a Technicolor consultant on set.

I’m now thinking that movies shot in black and white need the same thing—not to make sure you’ve strung enough lights to keep your actors from looking like corpses, but to keep your movie from looking like a parody of the thing it’s trying to emulate.

So it is with Steven Soderbergh’s 2006 homage to classic noir, The Good German.

Based on Joseph Kanon’s 2001 novel, The Good German is set in Berlin in the aftermath of VE Day. The buildings are bomb-scarred, offering plenty of dark corners for bad guys to lurk in.

Everybody’s selling whatever they have left—forged documents, black-market food, their own bodies—to get a little of that occupation money.

George Clooney is Jake Geismer, a New Republic journalist who’s covering the Potsdam Conference that will decide Germany’s fate.

After his military driver Tully (Tobey Maguire) gets murdered, Geismer is swept back into the orbit of Lena Brandt (Cate Blanchett), a former flame with a secret husband. In this Casablanca-esque triad, said husband Emil Brandt (Christian Oliver) is bizarro Victor Laszlo: not a freedom fighter, just a former Nazi scientist who knows how to build rockets that can deliver oh, say, atomic bombs on target. Which is why the Americans want to get to him before the Russians do.

He’s sorry for all the concentration inmates who died building his rockets, which is allegedly enough to make him the “good German” of the title. Okay, sure, but he still built the damn rockets.

The plot, in classic noir style, is deeply convoluted (I suspect Soderbergh regards this as a feature not a bug) but it basically boils down to a single objective: Geismer wants to get Lena out of Berlin alive. Maybe he’s still in love with her, maybe she’s a ticket to redemption, or maybe she’s that one good thing he can still bring out of this mess.

The unresolved mystery: was she worth saving?

Even in its final scene at Tempelhof Airport (one of the film’s more obvious nods to Casablanca), we’re denied that resolution. The ambiguity could work, but not if it ignores the larger question tied to its tail: was Germany worth saving if it meant letting people get away with murder?

Really, though, it’s not the story or even the actors who command our attention. The look of the film is the star of the show. This is where The Good German both delivers and disappoints.

As always, Soderbergh serves as his own D.P. (under the screen name Peter Andrews), and his attention to detail is exacting: the film stocks, the lighting, the exposure, the framing of shots are all period-authentic. I read that Soderbergh searched until he found old-school tungsten lights and I have no trouble believing it.

It’s a perfect simulacrum, and that’s where it gets its signals crossed. The shadows are perfect but the accents are wrong: modern actors just don’t talk that way anymore. They don’t hold their bodies like Alan Ladd and Gene Tierney. It casts an uncanny-valley effect over the movie. The closer it gets to the look of classic noir, the less it feels like the real thing.

Sometimes the imitation is so scrupulous that it feels like a goof. There’s a reason for that: obsessive accuracy is the domain of parody, not homage.

The best reimaginings of noir are the ones that play around with the formula. Fargo works as noir even though it replaces the urban jungle with small-town nowhere and fills the shadows with blinding white. It’s in genre spoofs like Young Frankenstein or The Man With Two Brains that every detail has to be just right. You ape the look of a particular genre so as to remind people what we love about it, as well as what’s silliest about it.

As I dove into the opening credits of The Good German I was tempted to think they were being silly on purpose. 4:3 Academy aspect ratio, seriously? Big blocky titles? Lush Max-Steineresque score? I was reminded less of Casablanca than Angels With Dirty Faces, the film-within-a-film of Home Alone. It was all just a bit too spot on.

It was somewhere around the moment that Tobey Maguire pays Cate Blanchett for sex and then punches her for making fun of him that I began to realize this might not be Angels With Dirty Faces. While religiously obeying every nuance of 1940s noir, Soderbergh also disobeys every stricture of the Hays Code: we get explicit sex, gratuitous violence, the military and law enforcement in a bad light. I didn’t check, but there must have been at least one scene where people kissed for more than three seconds. Things that were merely suggested in actual noir are pushed in our face in Soderbergh-noir.

It’s likely intended to expose the moral rot that lurks behind the relentless optimism of Allied victory, but the actual effect is much more jarring. In Casablanca, Rick says that Ilsa’s pleas remind him of the stories he used to hear that went with “the sound of a tinny piano playing the parlor downstairs.” Sure, Bogart doesn’t say whorehouse because he couldn’t—but the knife actually cuts deeper because he doesn’t have to.

In The Good German, Lena actually is selling her flesh to stay alive, and good old Tully has no trouble throwing the word in her face. It ought to shock, but it just feels gross.

One of the cardinal rules of any movie, regardless of genre, is that it only works if you want to be in the world that the movie shows us and you want to be in the company of its characters.

You have to want the lovers to get together and the innocent to be saved. You have to want the detective to avenge the victim and the victim to be worth avenging. The fact that noir movies so rarely end in justice being done or love triumphing—forget it, Jake, etc.—only strengthens our need to identify with the hero who walks down these mean streets who is not himself mean.

The worse people are, the more not being awful matters. You can even enjoy the bad guys being bad, because the moral compass is intact: for every Fat Man or Joel Cairo there’s a Sam Spade; for every Mike Yamagita or Jerry Lundegaard there’s a Marge Gunderson.

The bombed-out Berlin of The Good German is too busted-up to be alluring, and the characters are too horrible to be fun. Tully was a jerk and the world is no poorer for his death. As Lena, Cate Blanchett is way too steely for anyone to think she needs saving: not to mention that she’s very likely evil. Even the intrigue isn’t all that intriguing. The Americans want Emil Brandt to build ICBMs for them and he doesn’t want to. If they have to, they’ll kill him to keep him out of the hands of the Russians, especially if he keeps acting like a crybaby. Wherever we are in this movie, we’re a long way from Casablanca.

This is the fundamental mistake—not just Soderbergh’s, but that of ninety per cent of movies that call themselves neo-noir. In actual noir, it’s because the world is corrupt that acts of decency matter. Sam Spade avenges Miles Archer because when somebody kills your partner, you’re supposed to do something about it. Rick sends Ilsa back to Victor because the problems of three little people don’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world. If you can wrest one good and decent thing from the ashheap, it’s enough even if everything else goes to hell. Neo-noir, Soderbergh-noir, begins with the precept that none of it matters. The victims are no nobler than the villains, the heroes least of all. Doing the right thing is irrelevant because it all gets washed down the same gutter.

Although The Good German sets out to critique the sentimentality and unabashed patriotism of Casablanca, it truly belongs in the blank amorality of a James Ellroy novel like L.A. Confidential or The Black Dahlia. At least George Clooney doesn’t call anybody a shitbird.

As for the cast: everyone in The Good German gives us what we’ve come to expect from them. George Clooney is doing his square-jawed monotone thing, more than earning an award for Best Uniform Wearing. Cate Blanchett is her cool, refined self as—well, I’ll just say it: she’s a Jew and a Nazi. There are excellent cameos from Beau Bridges as a corrupt general and one of my favorite character actors, Leland Orser, as a JAG investigator with haunted gin eyes and a gut full of crooked deals.

The one false note is Tobey Maguire, in full-on Keane-painting big-eyes mode as Tully the stomach-punching soldier. Tully’s supposed to be cruel and crazy, but Maguire is just too dopey for the role. Even when he’s screaming, that crooked smile is never more than a wink away.

The cast is good, but nobody’s going to upstage the cinematography. The true lead of The Good German is the Eastman Plus-X 5231 black and white 35mm film stock the movie was shot on. If you’re going to watch it for anything, watch it for this.

It’s a pity because, despite everything I’ve said, there is a story worth telling in this movie.

It’s about an America that had just cleansed its conscience by victory in the “Good War,” and yet couldn’t stop itself from thinking ahead to the next enemy, our former allies the Soviets, and the weapons that would be needed to tame them.

Our desire for those rockets was so great that we were willing to give a moral pass to any Nazi with a briefcase full of blueprints. To make that movie, I think the script would have had to spend a lot more time with its title character—trying to fathom the motives of a man who’s determined to damn himself even though global powers are just as determined to exonerate him.

Is his contrition for real? Is “sorry” going to cut it? Most of all, what harm is this “good German” still capable of doing?

The movie occasionally flirts with its best themes but rarely dives in deep.

It’s giving us a perfect, glossy surface, as flawless as a mirror and just as shallow.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login