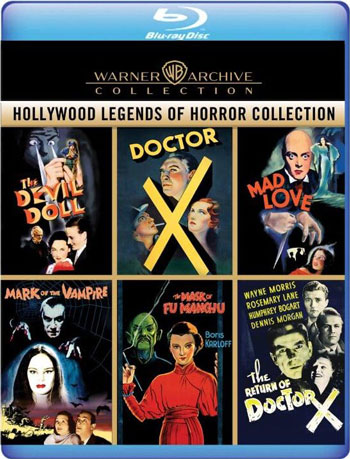

This spectacular collection is another fantastic release, collecting six horror films from the Warner Archive.

Doctor X

Two-strip technicolor is not every fan’s definition of “color,” but one cannot deny that the effect is wonderful here, going a long way toward building the murky, mysterious atmosphere for which the strange movie is famous.

Wonderful Warner Brothers sets take us from the foggy New York docks to a gothic Long Island mansion to a secret art deco laboratory.

Murders take place once every month at the midst of suspicious, unexplained experiments. Lithe and lovely Fay Wray, as the doctor’s daughter, screams no less than four times.

Director Michael Curtiz makes excellent use of shadows, silhouettes, and the transition shots with a shrouded moon.

The Gothic mansion, featured for almost an hour, is kind of an Old Dark House. But Lee Tracy’s wisecracking reporter never lets up, imposing on the horror every chance he gets. He’s like a personified joy buzzer.

Still, if you’re able to endure the scenes with Lee and focus on those with Atwill, the results can be very rewarding. The two standout scenes are one, halfway through, involving an elaborate lie-detector contraption and the other at its climax, involving how done it is, a real mind blower.

The Return of Doctor X

In 1939, Bogie was known as a reliable actor who played villains. His rise to stardom with High Sierra, The Maltese Falcon, and Casablanca was still years away. And so, here he plays Dr. Quesne performing sinister experiments alongside Dr. Flegg. Quesne has a pasty face and a shock of white hair. Flegg (John Litel of Invisible Agent and Flight to Mars) has a monocle and pointy beard. Both are great to watch. The action centers around a pair of heroes – a handsome doctor and a wisecracking reporter – trying to unravel the motives behind the murders (or resurrections, as the case may be).

The wisecracking reporter, a Kansas boy now living in NYC, is more likeable than the one in the original Doctor X. Other than the presence of a wisecracking reporter, a doctor whose last name begins with X, and multiple murders committed with the aid of a scalpel, this picture has nothing in common with the Curtiz-Atwill original. Modern-day viewers are often annoyed at the comedy in the original, but they might accept it here, since Return feels clean, bright, and modern like a 1940s film. The single lab scene is decent, but it depicts the resurrection of a rabbit rather than a human. A quick pace and a bunch of surprises will keep you on your toes.

Mark of the Vampire

Here is a film that can only be properly enjoyed by fans who know Dracula and other early vampire films well. It also helps if Mark of the Vampire is spoiled for you: all supernatural elements are faked. The head vampire (Bela Lugosi) and all the others are actors, hired to trick a villain into revealing himself.

Rather than thinking of it as a real vampire movie, think of it as an Old Dark House mystery with lighthearted vampire elements. As you watch, try to guess which characters are in on the ruse, and which are genuinely fooled. Lionel Barrymore plays the Van Helsing type, and Lionel Atwill plays the moustached inspector.

Fans who watch the film without knowing of the fakery are invariably disappointed. MGM gave Browning a larger budget than Universal gave him for Dracula, so the Gothic vampire elements are very well realized – the misty moors, the wavering cobwebs, the rats, the bats, the spiders, the candles, the clanky doors and chains. But fans feel cheated when it all turns out to be a theatrical fake. Even the most famous moment – Luna’s four-second flight on her giant bat wings – loses power. Lugosi only gets one line toward the end, as does Carol Borland who plays the great-looking Luna. One of the “rats” is obviously a possum, which is a New World animal anyway. Therefore, please go into this film knowing of the fakery, and enjoy it for what it is.

The Mask of Fu Manchu

After grunting and growling in Frankenstein and The Old Dark House, Boris Karloff finally spoke in a horror role in MGM’s Mask of Fu Manchu. The picture would seem to be insulting and offensive – it’s “white man” this and “yellow monster” that, it’s gratuitous with torture scenes, it’s lasciviously sexual (even homosexual for one brief late moment) – until you realize that it’s all a tongue-in-cheek pulp adventure intended to make us scream with shocked delight. Karloff (as Fu Manchu) and Myrna Loy (as his perverse daughter) knew full well the outrageousness of the ideas, the story, and the characters. Some latter-day viewers will still want to view the spectacle as an ugly manifestation of “yellow peril” paranoia. But I’ll bet that you, Dear Reader, will revel in the action and camp.

Karloff and Loy are wonderful in their roles, he the grinning sadist and she the grinning lecher. Lewis Stone (The Lost World) is good as Sir Nayland. I always like a hero who is getting on in his years. The torture devices include a giant bell, a see-saw above an alligator pit, and – most famously – spiked walls that slowly move to impale you. The “Asians” at Fu Manchu’s banquets include Indians, Arabs, and apparently Jews. The sets, the costumes, the shadows, the opium den, the “poison surgery” sequence, the Genghis Khan sword and mask, and everything else, are strong, inspired, and difficult to forget.

British novelist Sax Rohmer’s first Fu Manchu stories appeared in magazines in 1912. Fu Manchu first appeared in film in 1929 with Warner Oland (Werewolf of London), but the Asian villain didn’t make a big sensation until this 1932 film with Karloff. Later, Christopher Lee played Fu Manchu in five non-Hammer films beginning in 1965.

Mad Love

Lorre had already made The Man Who Knew Too Much for Alfred Hitchcock in England, but he first worked in Hollywood with MGM’s Mad Love, an adaptation of Maurice Renard’s 1920 novel The Hands of Orlac. Most fans agree that Lorre’s performance here is his second greatest after M. At first I thought he was overplaying it, but within 15 minutes he had me convinced he really was this obsessed, sensitive, pitiable, and strangely frightening little man. Early in the film his bald head marks him as an outsider; late in the film a strange disguise marks him as completely mad.

Unlike other adaptations (The Hands of Orlac 1924, Hands of Orlac 1960, Hands of a Stranger 1962), this one focuses not on the hapless Orlac wondering whether the murderer’s hands will turn him into a murderer, but on the strange Gogol in love with Orlac’s wife. Gogol’s descent into madness is the key to the film. The few flaws include an inappropriately jokey American reporter (muting the horror like Lee Tracy in Doctor X) and a conclusion that could have used some music.

Freund’s direction is very intent and precise. Numerous closeups give the three principal actors many chances to express emotion. Every shot seems to offer something visually exciting, like the little guillotine atop the cake, the pen in the wall, the white cockatoo, the carnivorous plant, and the famous confrontation in the bar. Gregg Toland, who co-shot the film, became most famous for his work with Orson Welles. Dimitri Tiomkin, who contributed the brief score, became most famous for his work with Frank Capra and Alfred Hitchcock; he also scored The Thing from Another World.

The Devil-Doll

The Devil-Doll is a unique combination of mad scientist tale and revenge tale. Despite the title, it’s science fiction rather than horror.It includes a great Frankensteinian lab scene early on, and a nutty female scientist who looks like a combination of Ernest Thesiger and the Monster’s bride. Shrunken people, used briefly for camp in Bride of Frankenstein, here become essential to the plot. Escaping from prison, a falsely-accused banker (Lionel Barrymore) joins up with scientists who plan to shrink people to doll size in order to save the world’s food supply.

Shrunken people, however, can only move if controlled by “the will of another.” The story is patently preposterous (i.e. what about the doll-people’s bodily functions? how and why do they obey mental commands? how do they know what to do without explicit instructions? how can the commanders see through their eyes?), but the movie is far better than most viewers will expect. The “dolls” are fun to watch-people, dogs, and a horse. The script contains surprises, including an unusual extended ending.

But the real key is Barrymore in one of the most unlikely successes of his long career. He gets a few minutes as himself at the beginning racking down the three bank managers who framed him 17 years before. He is excellent, and I don’t think it’s going too far to call this movie one of his greatest moments on screen. This movie also features the feisty and gorgeous Maureen O’Sullivan (Just Imagine, Tarzan and his Mate). John Baxter considers The Devil-Doll to be the first sustained treatment of miniaturization in SF film. Mike Mayo calls it Browning’s “most wonderfully maniacal work.” The story was inspired by “Burn, Witch, Burn!” by Abraham Merritt (1932).

You must be logged in to post a comment Login