Trek handled a number of subjects that creator Gene Roddenberry disguised by placing them within the context of a science fiction series including personal loyalty, authoritarianism, imperialism, class warfare, economics, racism, religion, human rights, sexism, feminism, and the role of technology. Yet to network executives, the series was simply, “Wagon Train to the stars.” Do you think Mr. Roddenberry truly believed in the utopian future and eternal optimism that he established in the series?

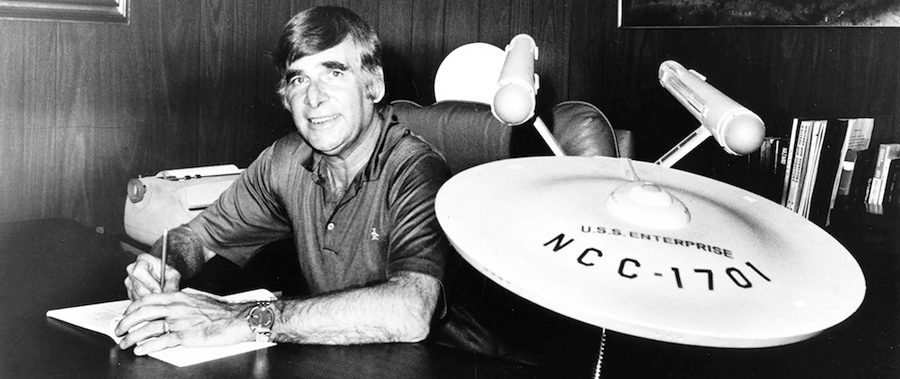

Image courtesy StarTrek.com

John Trimble: Gene was a secular humanist who truly believed that the human spirit will prevail, which led him to want to explore many of themes mentioned. He sold it to the “empty suits” (i.e., network executives) as “Wagon Train to the stars”, because that was something they could understand.

Carol Pinchefsky: Of course Gene Roddenberry believed in the utopian future. After all, he cast a Black woman as a military officer at a time when Black women were typically cast as maids. He also worked closely with George Takei, who suggested to Roddenberry that Star Trek have gay characters. I can’t imagine that Roddenberry didn’t know that George was gay. And yet he worked with a gay man during a virtulently homophobic time. That made him more open-minded and accepting than most people then (and to some extent, now).

It doesn’t mean he wasn’t flawed. He was a philanderer with a substance abuse problem. But Roddenberry imagined a beautiful future, a world of human accomplishment. Perhaps he wanted to live in that world himself.

Rich Handley: That’s a fascinating question. I think we all want to believe Roddenberry was, indeed, a utopian who believed in everything his writing espoused–and I do believe those were his actual beliefs. He was a man who eschewed warfare and ignorance and bigotry, and we have to respect him for that. What’s more, he pushed to have women and non-white actors on the bridge, which helped the industry to push past long insurmountable barriers.

At the same time, Gene was also a bit of a womanizer, and he wrote lyrics to the show’s opening theme that were never used, just so he could get partial credit and take some of the composer’s royalties. Also, he didn’t create these shows in a vacuum–without Gene L. Coon, D.C. Fontana and others, Star Trek would arguably not have been as good as it was, even though Roddenberry was portrayed (and portrayed himself) as the center of all things Trek. So despite his laudable ideals, Roddenberry nonetheless displayed some sexism and capitalistic opportunism in his actions.

That’s in no way meant to insult or demean Gene Roddenberry, for whom I hold immense respect. Like all of us, Gene was a complex and fallible individual, but I do think he was a visionary who deserves much of the respect and acclaim heaped on him. The question that matters most is not so much whether HE believed these things, but rather whether or not WE believed them after watching Star Trek–and by and large, we did and do. Roddenberry’s lasting legacy, whatever faults the man had, is that he created (with help from many others, of course) a franchise that remains healthy and thriving, and that has so much to tell us, even now… especially now, given the sorry state of the modern world. I doubt he’d have enjoyed living in it if he were alive today. Whether or not he was truly a utopian, we have largely failed to live up to utopian ideals.

Peter Briggs: I only know this subsequently from reading books like Mark Altman’s about the making of the show. But it’s clear he doggedly stuck to his view about the future he created. And why shouldn’t he? It’s his creation. But I also feel he sometimes “couldn’t see the wood for the trees”. Roddenberry was fallible – in short, human.

I feel also a lot of the shows have to be viewed in context. It seems a really popular dig to now make fun of “The Way To Eden”, for example. Now, that episode isn’t even in my Top 50 of the original 79, but if you look at it as a product of the era that created it: it’s a bunch of stuffed suits trying to explain to primetime middle class America exactly what the whole “Peace And Love Thing” is about…and, sympathetically to-boot. Personally, I think that episode is admirable for exactly that reason.

I guess the original “Wagon Train To The Stars” pitch might have sold the show, but that’s not really what Star Trek is at all. I feel Battlestar Galactica stole that premise and ran with it.

Steven Thompson: Lost in Space had been my go-to space show as a kid. When I started getting into Star Trek as a teenager, I quickly realized how different it was in that it was more serious, less colorful, and dealt frequently with what I came to think of as “grown-up issues” in the guise of science fiction. The characters seemed more real to me as well, not that Captain Kirk seemed all that “real,” but in comparison to Lost in Space’s Dr. Smith, y’know? It legitimately felt I guess like a rite of passage, moving on from childish science fiction to adult science fiction.

John Kirk: I think that’s a contention of pride with Star Trek fans. After all, the casting, the topics and the nature of the prolific and dynamically-minded writers behind the episodes would all support that notion. In fact, I touched upon this with Rod Roddenberry about that when I had the chance to interview him at SDCC a few years back and the simple answer is yes.

However, not everyone is perfect. Looking back with a 21st century mindset, it’s very easy to see the discrepancies. First, by Rod’s own admission, he and his dad weren’t always eye-to eye. If Gene was committed to a utopian view of the future, then perhaps he’d be a more liberal-minded and relaxed parent. Second, Gene was also a product of his time. He was a WW2 veteran, a former police officer and a Hollywood writer. These aren’t necessarily the occupations of a Utopian-minded individual. He also had fidelity issues in his marriage and while these may seem like criticisms, it’s very easy for someone to point them out as hypocrisies as well if we are to judge him on how he lived instead of what he espoused in his writing. However, one cannot know paradise unless he or she has experienced perdition first.

The 60’s were a time of well-intentioned growth and transition for America. Like many people, I think Gene genuinely believed in this type of societal growth and development but was finding his own way instead of actually knowing how to achieve it. I think it’s also important to remember that the ideas he forwarded in Star Trek were dreams, not blueprints. It wasn’t as if Star Trek was an instruction manual on how these dreams could be achieved, just that there was a belief in a future in which they could happen. The idea that Humanity could achieve a state of peace with each other, avoid planetary conflict and, seek personal growth instead of financial gain is a good one. Gene didn’t have to tell us how it would be achieved, just that it could. In that regard, I’d have to say yes.

Jeff Bond: I think Roddenberry started out very much as a strong television writer and producer who enjoyed using the medium to talk about issues of the day. He was humanistic, which was not unusual for a lot of people working in television. But he was willing to work within the confines and conventions of episodic television and he knew that a certain amount of action and sex was helpful in getting ratings and was part of the sugar coating necessary to help whatever message he might want to tell go down more easily. After Star Trek he spent a decade where he was much more a traveling lecturer than a television producer, and I think over those years he evolved into rather more a utopian philosopher than a producer. So when he did Star Trek: The Motion Picture and the early seasons of Star Trek: The Next Generation, he was in some ways shaping more of a utopian statement than he was an exciting movie or TV series. On The Motion Picture I think ultimately that was daring in terms of the other space movies being made at the time, so The Motion Picture is looked on more favorably now than it was when it was released. That’s not necessarily the case with The Next Generation’s first couple of years, where I think Roddenberry (and his attorney) were often at odds with what was needed to make good television. He was still ingenious about the basic ingredients and he was instrumental in providing the DNA forThe Next Generation (as was Bob Justman, David Gerrold, Dorothy Fontana and many others), but he had I think become a true believer in his own utopian vision and didn’t want to put squabbling, fallible, interesting human characters on screen.

Bob Greenberger: There’s little doubt Gene wanted to use Star Trek to address contemporary issues, building off his experiences on The Lieutenant. He was definitely in the forefront of television producers pushing the boundaries. Of course, he wanted to sell a cracking good television series that would run for years, that came first. As the chronicles show, he didn’t know that much about sci-fi and needed a crash course from Samuael A. Peeples and then turned to the leading sci-fi authors of the day, which gave him quite the education.

When he couldn’t sell anything but Trek and he hit the lecture circuit to make money, he was lauded as a futurist and bought into the praise, portraying himself as this great thinker. That was more the showman at first. It’s interesting to note his subsequent attempts at Sci-fi, developed in the more pessimistic 1970s, were dystopias, things like Planet Earth and Genesis II.

From there, he pushed towards a utopian future in the subsequent series, which proved to be creatively challenging for the The Next Generation producers.

Ian Spelling: I’m going to agree with much of what has been said above. I met Roddenberry once and had two extensive conversations with him for my college newspaper, only one of which I recorded (and later sold to Starlog, helping me get in the door there, for which I’m eternally grateful). He really sold this college kid on his optimistic, utopian vision. But, realistically speaking, he was an imperfect man who created a fantastic show about a world that SHOULD and COULD be a better place, with humans in a better place as a species. The early episodes give you that sense. Even much of the bible he created for the first pilot gives you that sense. But, and this is a big but, Star Trek was a television show, a piece of entertainment, a business property, a gamble for its backers. Roddenberry, particularly early on, got a lot of his vision into the episodes, but that faded a bit as he pulled back on the day to day job of producing. Other people — writers and producers — made their marks on the show. He made commercial decisions (IDIC ( Infinite Diversity in Infinite Combinations) pendant, anyone?). He made compromises. Some of the episodes are awful. He was both a creative dreamer and a financial pragmatist, and there’s no shame in that. The best of Star Trek stands the test of time, and he very proudly espoused that in his later years.

Bill Cunningham: My thought on this is the old adage, “Do as I say, and not as I do…” Yes, Roddenberry believed in the ultimate success of mankind, and that we will overcome our problems and put ourselves out into the stars. He was also subject to his own weaknesses, prejudices, and vices. One does not overshadow the other, but combine to give us a clearer picture of the human being, not the icon. We made the icon, he made the human being.

John E. Price: I personally believe the nature and role of Roddenberry’s “utopian” politics has been wildly exaggerated in popular culture. In closely reading the text – that is, the episodes themselves – Star Trek’s/Roddeberry’s optimism takes on a very specific context. In universe, the Federation begins out of the ashes of the third world war that nearly destroyed the human race. The stories we watch are of a humanity only a couple generations removed from that nuclear holocaust, a humanity that is determined against all odds to take full advantage of the second chance they’ve been given. Star Trek’s optimism then is not a naive, feel-good acceptance of blind hope, but rather the cautious optimism of faith – not in outsiders or in some deity, but in ourselves. Star Trek isn’t a show of utopia found, as it’s often portrayed in pop media; Kirk – Roddenberry’s mouthpiece – isn’t out there galloping across the cosmos a 23rd century Pangloss, he’s instead out there clawing inch by inch to maintain the fragile future that humanity has suffered so much to achieve – a chaotic trajectory that nearly falls apart weekly and requires every strength of Starfleet’s best to maintain.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login