There are some fantasy, science fiction, and horror films that not every fan has caught. Not every film ever made has been seen by the audience that lives for such fare. Some of these deserve another look, because sometimes not every film should remain obscure.

Sometimes, you’re not sure if you can stand all the allegory that’s standing in for other things…

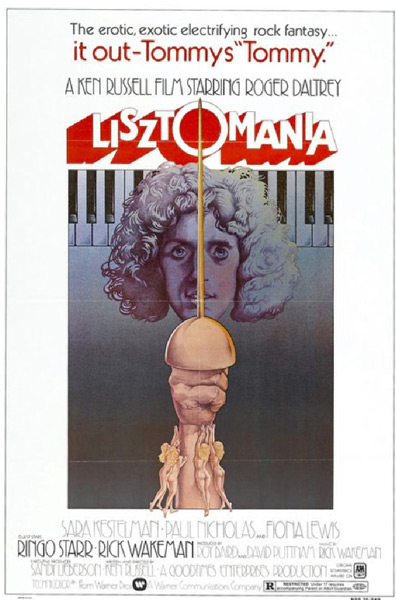

Listzomania (1975)

Distributed by: Warner Brothers

Directed by: Ken Russell

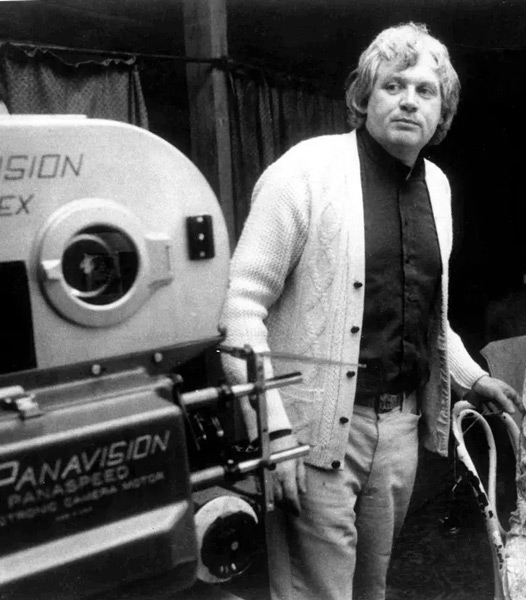

Ken Russell, 1971

Well, whatever else you may think of him, Ken Russel NEVER restrained himself.

And boy, did he just let it go all the way out there with this one:

We open cold in a bedchamber from the mid-19th century, as reimagined by the set department at Shepperton Studios. We find the composer Franz Liszt (Roger Daltrey) in bed with his music student and lover, Marie d’Agoult (Fiona Lewis), kissing and suckling her breasts in time with a metronome. Every now and then, Marie reaches over to make the metronome go faster, and Franz tries to keep up.

The scene though is interrupted by her husband the Count (John Justin). He tries to engage Franz in a duel, played to comic effect with blow-by-blow singing commentary offered on the action, before the wronged husband gets the upper hand and seals his unfaithful wife and her lover into a piano that’s placed on the train tracks to get run over by a locomotive…

Or does it? Is it a flashback, a simile, or just another of those scenes Ken Russel likes to insert at random to shock people? Who knows, and it’s not worth mulling as the film finally gets to the opening credits and goes to a pre-show party. Franz is waiting to go onstage, with the drinking and debauching much like what Daltrey himself probably saw on tour with the Who back then.

While he’s schmoozing with his contemporaries, into the part sneaks a raw unknown talent, Richard Wagner (Paul Nicholas). Ends up Franz has heard of Richard before, and is about to go out on stage to perform variations on Richard’s first opera, Rienzi. Which you’d think Richard would be happy to see, save for the fact that he’s not into the whole screaming-girls-at-a-concert scene:

This ends up being one of Franz’s last performances, though. Despite the protestations of his now-wife Marie, and the chiding of their daughter Cosima (Veronica Quilligan), Franz goes to Russia to look for patronage from the Czar. While there, he falls for and takes up with the Russian/Polish Princess Carolyne (Sarah Kestleman), who promises him inspiration to make great music, for the price of his soul.

Part of the bargain involves running away with Carolyne once she gets her divorce and marrying her in Rome. Unfortunately for her, His Holiness the Pope (Ringo Starr) does not sign off on her being able to remarry, which Franz takes as a sign that yes, he should take up holy orders, and becomes a Franciscan abbe.

His Holiness, a true homo mundanus as he smirks while making snide remarks about faith and catechism, gives Franz a mission: He wants him to redeem Richard. Franz’s old discovery has moved on to making what His Holiness considers “evil music.” Franz is told that Richard borrowed a lot from Franz to make it, up to and including marrying Cosima, and that he must redeem Richard before his creation leads to evil coming into the world, although it may be too late by the time the two composer meet…

Franz and Richard with Richard’s “creation,” played by Rick Wakeman

The plot sounds bonkers, and yes, it is, even though much of this did actually occur. The friendship, the promotion, the affairs and marriages, even the actual Listzomania that took place when Liszt was performing, all of it actually happened.

The main liberty Russel’s script takes is in manufacturing how the evil Wagner stole from the beatific Liszt. This is less of an invention for the sake of the film, though, than it is a theme Russel brings up as often as he can; his earlier film Mahler likewise made this point, going so far as to have Cosima Wagner portrayed as an SM queen in a leather mini-dress while wielding whips.

Weirdly, the events depicted in the film are given much more deferential treatment than the music that came out of these times. When you do a film about two major Classical composers, and the credits read “Music by Rick Wakeman with assists from Franz Liszt and Richard Wagner,” you know the soundtrack is going to leave a lot of unhappy people in its wake.

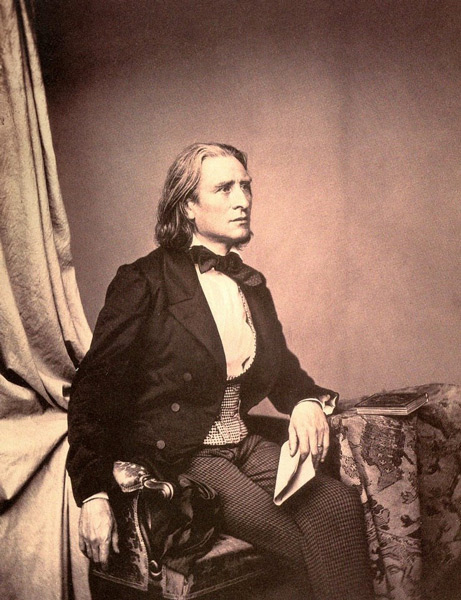

Franz Liszt, 1846

In terms of directorial choices here, Russel likewise goes big as shockingly as he can. It’s not enough to just have a set piece if Russel can epically exaggerate it, burning it into your retinas. Why just show Franz’s tryst with Carolyne normally, if you can Franz’s member grow to ten feet long for him to ride in a musical number? Why just mention that Richard’s operas contained hateful messages about Jews, when you can have an ugly stereotype ravage seven nude Rhinemaidens in succession? The only thing limiting Russel in the film is his audacity and budget.

This was certainly the most ambitious and outlandish of all of Russel’s composer films, which in addition to Mahler include The Music Lovers and Tommy, about Tchaikovsky and Townshend respectively. It was also likely the most impulsive; work started on the film while Tommy was still in post-production, before a final script was written, with Daltrey given the lead over the director’s first choice, Mick Jagger, because he was immediately available.

Most of the cast in fact didn’t seem prepared to fill any of their roles, which is to be expected when they started to shoot before the script was finished. Daltrey would note in later interviews that he wasn’t prepared for the role, going right from playing the mute Tommy who didn’t have lines in the last film into the lead as Liszt, and it shows. The only one who seemed to be raring to go for this was Russell, who managed to convince everyone that the momentum from working on Tommy would carry over into this quick-draw snapshot production.

A few moments of self-reflection, though, might have saved this from gaining a reputation as a self-indulgent disaster. The early scenes of Liszt performing, where parallels could be raised between the Romantic classical movement and the contemporary rock scene, are fascinating and work on their own, and with a bit less reliance on shock there could have been a more thoughtful movie with something to say.

Instead, we got a film that cemented our perception of Ken Russel as a wild madman with no filter. Amidst all the other damage done, it’d be the last time Russel would be able to look at a composer. His production partners at the time refused to finance another film of his, which ended the director’s hope of doing another composer film about George Gershwin.

Because the movie under-performed, no one was rhapsodic over getting into bed with Russel…

You must be logged in to post a comment Login