Shout Factory

Cameras used to be law enforcement’s best friend.

From 1989 to 2013, Fox’s COPS stoked the national appetite for heroes in uniform chasing down ruthless (and often shirtless) drug dealers and domestic abusers under the stark light of a bobbing handheld.

Even though it was called Reality TV, we assumed there would be limits on how real things got. The presence of the camera meant that nobody was going to die.

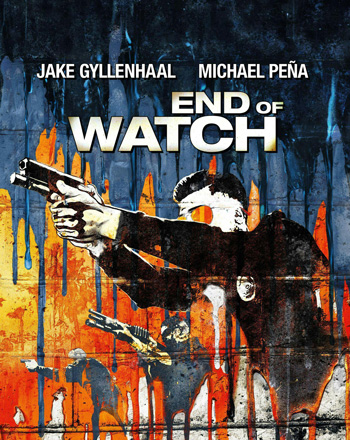

David Ayer’s 2012 End of Watch appeared at the tag end of the COPS era, and it also begins with police chasing bad guys. There’s no cutting around: Ayer keeps us solidly focused on the dashboard cam. We’re seeing it as the cops do. The pursuit ends in a shooting—a “good” shooting, as cops call it, since one of the suspects tries to shoot them first. They shrug it off: this is the job.

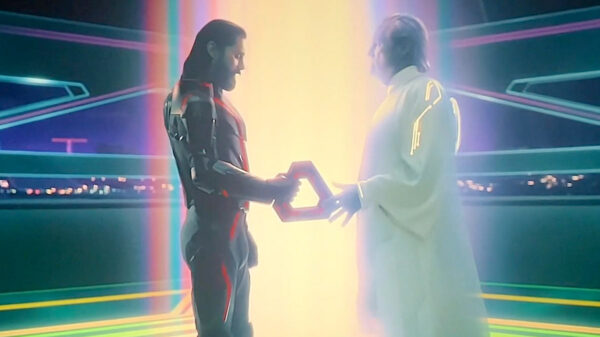

Like COPS, End of Watch shows us police who are unafraid to be caught on video, since (as they see it) the truth can only prove them right. LAPD officer Brian Taylor (Jake Gyllenhaal) even brings his own movie camera on patrol with his partner Mike Zavala (Michael Peña) in South Central Los Angeles. We’re told he’s recording his daily work for a college course assignment.

Although it gives the film an improvised, bantering vibe—punctuated with frequent moments of horror—End of Watch isn’t found-footage. The digital camera is too cumbersome for plausibility (one scene shows Taylor filming with one hand while aiming his service weapon with the other), so it’s mostly abandoned. There are various dashcam shots and the cops wear bodycams, but in that pre-Ferguson era these were still seen as protection for cops, not their victims. We only see what they show us.

In The Last Watch, this is Ayer’s way of assuring us that everything we’re about to see is true: everyone knows that shakycams don’t lie. We are in Taylor’s and Zavala’s world, seeing the grim job of policing through their eyes.

And what those eyes see in two hours. Although the movie plays like one long patrol through South Central Los Angeles, it actually unfolds across an entire year: Zavala’s wife gets pregnant at the start of the movie and gives birth before the end. (This must have been some college course). It gives the impression that all cops do is drive from one nightmare to the next.

After being cleared of wrongdoing in the shooting, Taylor and Zavala are assigned a new patrol with the ominous designation 13-x-13. A domestic call about missing children reveals both toddlers tied up with duct tape in a closet. A truck they pull over for a routine citation is driven by a gang “cowboy” with a blingy AK-47 and a soup tin full of cash. A routine check on a senior citizen reveals a kitchen full of drugs and a mass grave of headless victims. They even rush into a burning building and pull children to safety: those boys from the fire department are just too slow for Taylor and Zavala.

All of this is well told—Gyllenhaal is playing a more sympathetic version of the grunt he gave us in Jarhead—and the truth is that cops do face these kinds of situations. Although some critics dismissed it as “copaganda” at time of release, End of Watch shows up with receipts. Ayer grew up in South Los Angeles, and has remarked that many kids in his neighborhood either chose to become criminals or cops. His film isn’t so much about sticking up for the LAPD as sticking by his friends.

In some ways, he’s atoning for earlier work. Ayer’s screenplay for Training Day showed us a much darker vision of policing—a world of compromise, corruption, and blind-eye-turning that is both reprehensible and yet also grimly necessary. Orwell’s frequently misquoted observation—”Those who ‘abjure’ violence can only do so because others are committing violence on their behalf”—echoes what Training Day rubs in our face: injustice is real, and it’s disgusting, but it’s also the job.

End of Watch deals with that moral obstruction by sidestepping it entirely. There are no knees on throats in this movie, no suspects shot while resisting arrest. Zavala and Taylor don’t do a single thing they’d be afraid to put into his college assignment. At one point, Zavala takes off his badge and invites a gang member to duke it out. After he wins, Zavala shows his sense of honor by not citing him for assaulting an officer. The gangbanger later returns the favor by warning Zavala that he and Taylor have been “greenlit” for execution by a rival gang.

There’s a moral here—not necessarily the worst I’ve heard—that good policing happens when you have good cops. But there are two problems with how the movie plays that out. One, we never see any bad cops. Two, by movie’s end the story has torn that moral to shreds.

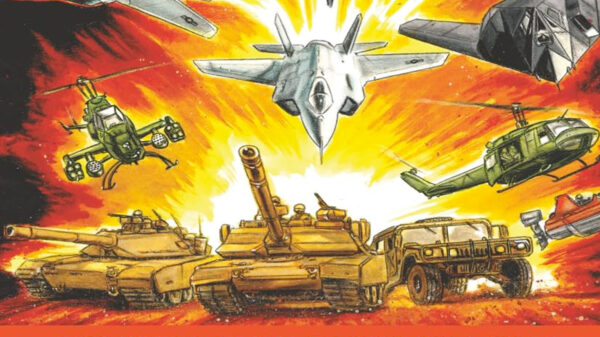

Zavala and Taylor are effective because they know the territory: but the territory is changing. O.G. Bloods and Crips are being pushed out by Mexican Sinaloa cartel. New gangs, new rules. Or rather, no rules. The Black gangs keep their distance from cops. Their Hispanic successors plan to execute Zavala and Taylor because the cops told them to turn down the music at a house party.

The implication is hard to miss: if cops are going to survive on the streets, they need to realize they’re at war with a much deadlier enemy. Taylor, like Gyllenhaal’s character in Jarhead, was a Marine. During an attempted gang assassination, Taylor tells Zavala to fight back the way he did in the war. The notion that police need to start acting like soldiers—that neighborhoods are not filled with civilians to be protected but enemies to be fought—is treated uncritically. Two years after the release of End of Watch, that mindset would be used to justify the deaths of Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, and Freddie Gray.

This lesson is hammered in by a brief appearance from ICE, who show up in full tactical gear to tell Zavala and Taylor that they’re in way over their heads against these cartel gangs. The image of an ICE that’s actually going after real hardened criminals instead of five-year-olds and senior citizens—an ICE that doesn’t wear masks—lands harshly in these jaded times.

End of Watch was made at a time when it was just possible to pull off a movie this unabashedly sympathetic to law enforcement. The movie came out two decades after the beating of Rodney King and ten years before the death of George Floyd. This was not exactly an era of good feelings, but there were fewer headlines about police brutality. We’d convinced ourselves that video would keep everyone accountable. The same cameras that recorded what cops saw would also record what cops did.

This has proven true, though not in the way the experts imagined. It’s not bodycams that have shed light on police brutality, but the cell phones held high by onlookers. We find truth not in one single lens, but many.

The title End of Watch refers to the end of a policeman’s shift, but it’s also applied to an officer who’s died in the line of duty. The movie’s rare breaks from patrol duty—Taylor gets engaged and married to Janet (Anna Kendrick), who has zero idea what she’s in for—are overshadowed by hints of that other, much more final way that a policeman’s shift can end. At one point, Janet plays around with Taylor’s service revolver and wonders if he’ll take her shooting. Later, at their wedding, Zavala’s toast leads Janet to notice just how many widows are in the room.

But there is a third, maybe unintentional but definitely resonant meaning to “end of watch.” It is the knowledge that our eyes can only show us so much. We only see what the camera shows us. We only see what we want the camera to show us. David Ayer shows us cops who only ever do the right thing. It’s not that this vision is a lie—most police are just doing their jobs—but if the charge is that some cops kill without justice, it’s not exactly a convincing rebuttal to say “but these cops don’t.”

I was entertained by End of Watch, and I was frequently disturbed by it, but in many ways I was also grateful. Grateful for the chance to see police as they see themselves. Grateful for a pro-law enforcement movie that focused more on victims than filling bad guys with hot lead. That didn’t show cops as hardened or broken, but as people who knew how to stay married and maintain friendships. Just as Goodfellas blew up every stereotype we had about the mob, End of Watch in its modest way blows up the stereotypes of old-style cop movies. They’re not Dirty Harrys. They’re just working stiffs doing their jobs. Seeing them this way is both the most hopeful—and the most cautionary—reality that Dave Ayer’s camera reveals to us.

Extras include audio commentary, deleted scenes, and featurettes.