Disney / Buena Vista

Once upon a time there was an animation studio that loved cartoons very, very much.

So much that, in 1937, it made its very first feature-length animated film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Maybe it wasn’t the first animated feature ever but it was the first one I ever saw, so I’m going to give it to Walt.

Snow White was a breakthrough.

It was the debut of Disney’s multiplane camera, bringing deep focus and depth to animation. It was the studio’s first use of rotoscoping and life drawing to create realistic human characters.

Effects that were damned difficult to pull off at the time—reflections, soap bubbles, wind—perfected the illusion.

Songs revealed character and moved the plot forward. Disney set up assembly lines to churn out four hundred thousand animation cels, but this was no factory hack job.

The concept artists studied up on German romanticism and pre-Raphaelite painting. Details reward a closer viewing: literally everything in the dwarfs’ home has a face or animal carved into it. And it’s visual storytelling at its best. We don’t see the Queen hit the ground when she falls, but we know when it happens—because that’s when her beloved vultures swoop down out of frame.

This is not to proclaim Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs the Citizen Kane of princess movies.

The writers were too steeped in gag writing to build a narrative. We spend five minutes watching forest creatures clean up the dwarfs’ home and another seven watching the dwarfs learn how to use soap (why do they even have soap?). Walt had some germophobia issues.

Then there’s Snow White: she has lips as red as blood, hair as black as ebony, and a character arc as thin as paper. She just doesn’t do anything except clean house, almost die, and run away with a guy she barely knows. Thus setting the standard for many Disney princesses to come.

No one can accuse the live-action Show White (Rachel Zegler) of doing nothing.

She picks apples that don’t belong to her. She feeds the hungry. She gets into forest battles. She leads a revolution. She looks for her missing father and rescues outlaws and reminds the Evil Queen’s guards of who they were in the good old days when they made pies and shoes instead of rounding people up in the dead of night and okay I just figured out what this movie’s talking about.

When I say that the live-action Snow White feels familiar, I’m not talking about the movie it’s based on.

Yes, the signature moments are there—wishing well, check; Dopey putting diamonds in his eyes, check—yet Snow White’s primary source isn’t the movie it’s supposedly based on. There’s the endless exposition song about how great family is (Encanto, Frozen 2); the roguish rebel boyfriend who’s there to make the heroine seem more like a tomboy (Tangled, Frozen); the drag-inspired villainess who drops ironic asides to no one in particular (The Little Mermaid, Tangled, The Emperor’s New Groove). Most notably, there’s the reworking of a familiar throwaway line into a stirring, be-yourself ethos: fairy-tale icon as self-actualization metaphor. It was “finding your muchness” in Alice Through the Looking Glass and “melting the frozen heart” in Frozen. Now, we’re told that being “fairest in the land” has nothing to do with beauty—it’s about being fair, you see, god knows we wouldn’t want to imply that Snow White is the heroine because she’s beautiful, that would be shallow. This Snow White is going to restore fairness to the land, get it? Forget multiplane cameras: this Snow White has actual depth.

Never seen that before. Except for when we saw it in the live-action Mulan. And the live-action Alice in Wonderland. And the live-action Beauty and the Beast. The earlier remakes ripped off the animated originals. Snow White is ripping off other Disney remakes.

And that opening number really does go on forever. This is how we learn that Snow White’s parents were kind and just people and raised their daughter to be kind and just until mom died and dad remarried and the stepmother revealed how evil she was by putting on a cowl and a really sharp crown. Know how long it took for the original Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs to set all this up? Fifty-two seconds.

In reaching for its own message—Snow doesn’t want a boyfriend, she wants to save her people—the movie sacrifices the subtle layers of its source.

In the Grimms’ fairy tale, Snow White’s relationship with the Queen is a rich lode to mine.

An aging stepmother is so jealous of her stepdaughter’s beauty that she tries to have her killed. So jealous that she will sacrifice her beauty and transform herself into an aged hag. The story deals in hard truths. Sometimes your new mom won’t love you. She may in fact work you like a prisoner on a chain gang. Once you hit puberty, other women will start to see you as competition. Being a woman means taking care of little humanoids who have zero sense of personal hygiene. Yes, you will get your prince, but first you have to lie there not moving a muscle while he kisses you. Like most fairy tales, Grimms’ “Snow White” is about helping kids—specifically girls—get used to the grimmer side of life.

The 1937 Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs passes these events through the story without investigating them.

Snow accepts the job of housekeeper gladly.

The Queen hates Snow because she’s jealous. When she transforms from her sleek, Joan-Crawford-inspired self into the Witch—a sequence that terrified three-year-old me so much that I crawled under the theatre seat—she completely abandons herself to her new appearance. She actually seems a lot happier, a lot more herself, as a crone: she can hang out with vultures and cackle about murder. This is a good villain.

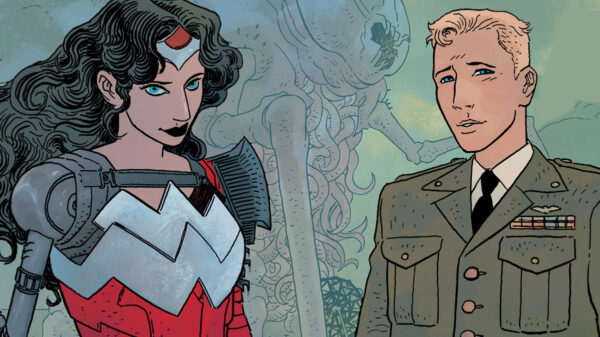

Live-action Snow White has a lot more trouble picking a lane for the evil Queen.

I suspect that Gal Gadot wrote “play intensely” a lot in her script. It’s unclear why this Queen is so mean. The Magic Mirror mutters something about a prophecy, that she’ll lose her regal power when she’s no longer “fairest in the land” (in case you forget the double meaning of that phrase, the movie will remind you several times).

At times it seems like the Queen’s trying to teach Snow how to be hard-hearted and feared, like we’re in a fairy-tale version of Training Day. Mainly, she just doesn’t seem to enjoy being evil, which is kind of a basic prerequisite for Disney villains. The 1937 Queen/Witch waves the poisoned apple at her pet crow and jokes “Want a bite?” Gal Gadot sulks like she just read the comments on her “Imagine” video.

There’s a weird kind of fan service that Disney does in its live-action remakes, that seems less about improving the film and more about insulating it from criticism. Sometimes they lean into the fan theories (yes, Lafou is gay) and sometimes they paper it over (no, Belle doesn’t have Stockholm Syndrome). In the case of Snow White, the screenwriter Erin Cressida Wilson—known mainly for creepy/erotic/quirky grownup films like Secretary and Chloe—seems determined to scrub away the idea of a princess who falls in love with the first guy in tights. Jonathan (Andrew Burnap) is a strolling actor who’s been forced into a life of banditry. He and Snow predictably fall in love—not because they’re teenagers, but because they share a sense of compassion and (here we go) fairness. Which gives them about as much chemistry as a freshman sociology lecture. Rachel Zegler doesn’t break out of I’ve-just-met-a-girl-named-Maria mode. Burnap is basically a smirk with legs.

I suppose we may as well stop avoiding the dwarfs. There was some pre-release controversy about the studio’s decision to use CGI instead of casting little people in the parts—a move made odder by the decision to include a non-dwarf character who’s an actual little person. The design of the dwarfs shows how desolate a place the uncanny valley is. There’s just enough realism in the lips and eyes to make the unreal parts even weirder: Disney sure spent a lot of money to achieve the Clutch Cargo effect.

I could forgive this. I could even forgive how they keep reminding us of their names, like we’ll need to know which one Bashful is later on. The one thing I can’t forgive is Dopey. Somebody at Disney decided that Dopey must find his voice.

Why doesn’t Dopey talk?

The 1937 movie tosses it off—he doesn’t know because he never tried. This being a twenty-first century remake, there must be a reason dating from childhood, and the reason is that he’s traumatized by something the Queen did. In 1937, Snow teaches Dopey to whistle. In the new version, she teaches him courage, which Dopey summons when he gives a rousing speech to his fellow dwarfs. I think the filmmakers must have been going for something like Charlie Chaplin having the Tramp speak at the end of The Great Dictator. The effect is more like watching MAD Magazine’s Alfred E. Neuman recite a speech from Bravehart.

The trouble is that Snow White isn’t just a bad movie: it’s a bad kind of movie.

The kind where you remake a property because it’s beloved by millions and then ignore everything that people loved about it. The kind where every motivation requires a backstory and there’s always a prophecy. Worst of all, the kind where nothing can be implied and everything has to be treated literally.

1937 Snow White thought the trees had faces and were trying to kill her, and had a good laugh at herself when she realized her mistake (she even sang a song about it).

In the 2025 remake, the trees are actually clawing at her dress like Bad Treebeard. For all the talk about 1937 Snow White lacking depth, she actually earns all the love she gets. In the original, the birds and squirrels decide to help Snow because she rescues a baby bird. In the new version, the forest critters just start helping her because I guess they heard the opening narration and knew she was the good guy. Modern screenplays don’t define a character through their actions. They announce who the character is and expect us to fall in line.

The 2025 Snow White did one good deed: it made me go back and watch the original.

This time, I didn’t scream and crawl away when the Witch appeared. I could love the movie, even the parts where the plot comes to a complete standstill (at one point we’re literally watching a turtle trying to climb a flight of stairs). I could love the movie in spite of Snow’s kewpie-doll voice and the scene where Grumpy tries to murder a sleeping Snow White with a pick axe. I could love it because there is love in the work. The animators dared themselves to do what no one had ever done before. They took pains to get the sheen on a bar of soap just right and make a falling boulder look like it weighs two tons. I am so grateful that I rediscovered this movie and learned to face it like an adult.

If it takes a bad movie to make you appreciate a good one, then 2025 Snow White deserves at least that much praise.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login