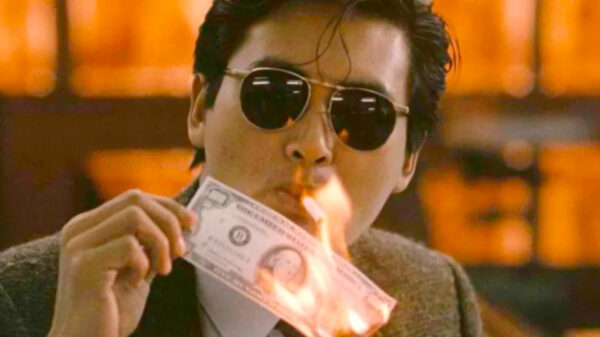

Paramount Pictures

The last time we saw Dexter Morgan, he was wearing a bullet in his chest, fired by his own son. Fortunately for fans of the show, he was only mostly dead. In Dexter: Resurrection, he gets to find out how much of him survived that wound.

The audience has to answer a similar question: how much of the Dexter Morgan that people loved is still alive in the show? Opinions differ as to when the original series lost its way, but at least everyone agrees what Dexter was like at its best.

Back in the early aughts, novelist Jeff Lindsay made two keen observations about: 1) people like serial killers; 2) people like people who catch serial killers. He doubled down with a serial-killer hunter who was a serial killer. Thus was born Darkly Dreaming Dexter, the basis for the Showtime series Dexter.

The adaptation stuck close to Lindsay’s winning formula. Dexter Morgan (Six Feet Under’s Michael C. Hall)—Miami P.D. blood-spatter expert by day, the infamous Bay Harbor Butcher by night—only kills people who’ve done something to deserve it.

This absolves the audience of the guilt of rooting for a psychopath, particularly as we’re told it was witnessing his mother’s murder that put him on the path to vengeance.

He has his sister Debra (Jennifer Carpenter) to draw him into the light and the code of his father Harry (James Remar) to keep him from descending into darkness. Since Harry shows up as a phantom in Dexter’s mind—a counterbalance to the “Dark Passenger” that drives him to kill—he even has someone to talk to about his work.

This was the pattern that got us through the first four seasons of Dexter. Dexter binds his lawful prey in plastic wrap, he stabs them dead with his happy knife, his police buddies almost-but-not-quite finger him as the Bay Harbor Butcher, he almost-but-not-quite crosses over into becoming evil himself. Repeat.

Despite his family and colleagues, Dexter’s defining fear is loneliness, something that Hall expresses with one of the most deeply furrowed brows in show business. He’s constantly looking for someone who can embrace the Dark Passenger, even if that someone is another killer. This eventually led to what must have been a very big day in the writers’ room: what if Dexter settles down with a nice woman and has a kid?

This was one of several dealbreakers for fans (another was when Deb decided she was in love with her brother—sorry, adoptive brother—leading to charges that Dexter had descended into step-sibling porn). Changing diapers did not bode well for his future as an avenging angel.

Dexter: Resurrection begins with that son, Harrison (Jack Alcott), now a young man working in a tony New York hotel. He still believes Dexter is dead. One night he kills a would-be rohypnol rapist, looks into the blood-spattered mirror, and realizes what so many of us are eventually forced to confront: he’s become his father.

Knowing the kid must have made a mistake covering up his crimes (spoiler: he did), Dexter breaks himself out of hospital. We fully expect Dexter to swoop into New York and save his son from the homicide detectives who’ve already fingered him for the murder. And then he… doesn’t.

He was going to, but then he made new friends. First it’s a rideshare driver with the on-the-nose moniker Blessing Kamara (Ntare Guma Mbaho Mwine). Blessing isn’t quite a Magical Negro, but he definitely makes job- and apartment-hunting a lot easier for Dexter. Blessing also kindly moves the plot along by telling him about a serial killer who beheads rideshare drivers, and who has the nerve to steal Dexter’s nickname: they call him the Dark Passenger.

Dexter settles his copyright dispute with a trip to his killing room. After dispatching his rival and assuming his identity, he’s invited to join his fellow serial killers in a kind of murderers’ executive lounge. The group was assembled, for reasons slow to be revealed, by billionaire Leon Prater (Peter Dinklage) and his enforcer Charley (Uma Thurman). They accept him because they think he’s somebody else.

Maybe he is. Dexter: Resurrection is also a rebirth for the series. It’s a back-to-basics, can-we-please-see-him-killing-bad-guys return to form. You don’t think he’s going to outsmart his prey until he does. He knows who he is and why he’s here, no girlfriends to slow him down. Clearly showrunners Clyde Phillips and James Manos, Jr. spent some time cruising the fan subReddits before they sat down to write.

In spite of their decision to play to Dexter’s strengths—and it has a lot to play—the new series occasionally has trouble picking a lane. Wasn’t saving his son a big deal? Eh, it’ll keep. Resurrected Dexter is commitment-phobic. Blessing keeps inviting him to dinner and he won’t even show up with a bottle of wine. He gets a job as a rideshare driver and never picks up any passengers. He’s got to have the app’s worst driver ratings.

The company he drives for, incidentally, is UrCar (pronounced “your car”), a name that must cause a lot of confusion for passengers: at one point Hall has to speak the Abbott-and-Costelloesque line, “Don’t take my UrCar”.

The closest that Dexter gets to a real connection to anyone (apart from ghost-dad Harry) is the cohort of serial killers he meets in Mr. I-Drink-and-I-Know-Things’s elegant mansion. That is, the script has Dexter say that he feels connected to them, but Michael C. Hall keeps looking at them like he’s stuck on the worst panel at DragonCon. The only one worthy of his gaze is a fellow dark angel named Mia, played with poise by Krysten Ritter, aka Jesse Pinkman’s junkie girlfriend Jane on Breaking Bad.

Mia (trade name Lady Vengeance) says she became a killer because her stepfather molested her sister and now she only targets sexual predators. Only kills bad people, you say? A code? This is a dating green light for Dexter.

This may or may not be her actual motive—I’ll just say that you don’t call Krysten Ritter to play people who aren’t screwed up—but it does shine a light on one of the Dexter franchise’s deeper flaws: the idea of serial murder as traumatic response.

It’s a myth that deserved to die long ago. In 1889, newspapers speculated that Jack the Ripper killed prostitutes because one of them gave him syphilis (which says a lot more about society’s obsessions than the killer’s). As the late, lamented series Mindhunter confirmed, the motives of real psychopaths tend to be unsatisfyingly weird. Charles Manson was mad at a record producer and wanted to blame Black Panthers for an unrelated murder: that’s why Sharon Tate died. The Green River Killer, Gary Ridgeway, told police that he targeted hookers because he didn’t like paying for sex.

We’re meant to believe that everyone—Dexter, Blessing, Prater, probably the caterers at Prater’s parties—is who they are because of something that happened to them in childhood. Psychology aside, it’s not great storytelling. Audiences are far less interested in backstory than most screenwriters seem to realize: it un-darkens the darkness. In the novel The Silence of the Lambs, Clarice asks Hannibal Lecter what happened to him, and he replies: “Nothing happened to me, Officer Starling. I happened.” That’s how you write a serial killer.

The need for motive makes Dexter more reassuring than a TV show about a serial murderer ought to be. We know why Dexter kills and so does he. It opens the possibility that if witnessing his mother’s death made him a killer, maybe some other experience can make him not a killer. This hopeful belief (if shows about serial murders can be hopeful) is the foundation of the Harrison Morgan subplot. Maybe there’s a chance for him not to be his father’s son.

Which leads to a separate but closely related problem: the twin forces of good and evil competing for Dexter’s soul.

Dexter was born in an era of TV shows about antiheroes with one-word titles: House, Castle, Bones, Alias, Weeds, Psych, Angel, Profit, Monk, Oz (okay, technically it was House, M.D., but nobody called it that).

Each of these characters was a walking contradiction, built on a question that must never be answered or (so the theory goes) the character would become stale. Dexter started out as a book series character, and that’s how series characters work. Does he kill because he needs to or only because he wants to? It’s a good question, but to make it unanswerable leaves the character with nowhere to go.

At times, Dexter seemed to toy with the idea that its title character would have an arc. He might even emerge from the blood-red shadows of his childhood to become a complete person who could love and be loved, presumably without having to face the penalty for his crimes.

But we could never quite get there. The showrunners keep bringing him back for new seasons, and if he’s going to keep coming back then he can never change. We don’t want him to. His mother’s murderer may have made him a killer, but we the audience are the ones who keep him killing. We’re his true Dark Passengers.

The creators of Dexter: Resurrection have elected to insulate him from a changing world. Yes, there’s iPhones and Beats by Dre, but that’s product placement. He lives in a New York where people still find things out by reading the bundle of newspapers as it falls next to the newsstand. He seems to have no trouble paying New York rent without a steady job. There are physical dossiers in brown folders. Serial killers seem almost nostalgic in an era of mass school shootings, and nostalgia is where we are. We’re being invited back to the television of twenty years ago.

Does it work? It starts slow but quickens mid-season as Dexter sours on his serial connections and starts to get some killing done. If only his colleagues were as tough as their reputations, we might have had some real conflict. Thurman is in full ice-queen mode and Dinklage does some great fanboy/villain geeking out over Dexter’s technique (a retread of The Incredibles’ Syndrome), but they kick into boss-battle mode far too late in the season. I expected more from Tyrion and The Bride.

If all you want to do is enjoy Dexter: Resurrection, you’re in luck. Dexter’s code snaps him right back where we want him: standing over that table looking down with his slides all prepped and his knife ready to plunge.

The series has snapped back as well. Most of the bad decisions of the original series have been tossed into the furnace like Dexter’s victims. We still have to deal with some of the show’s worst tics, like his interior monologue telling us what to notice and how to feel. But things like that tend to happen when you’re in the grip of a master control freak like Dexter Morgan.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login