Shout Factory

Hong Kong cinema of the 1980’s was an explosion of creativity as the New Wave of filmmakers that had broken into the industry in the waning years of the 1970’s found their voices and began to produce films of such visceral power that they remain legendary to this day.

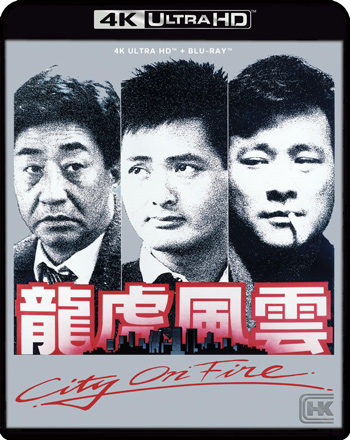

Perhaps the two that stand above all others from this period are John Woo’s legendary gangster melodrama A Better Tomorrow from 1986, and Ringo Lam’s pressure cooker of a police thriller City on Fire.

It’s easy to see how the films became linked: only six months separated their release and they both earned star Chow Yun-fat the status of leading man and back to back Best Actor awards at the Hong Kong film awards. They set a standard for neo-noir, not just Chinese neo-noir but the genre as a whole, that wouldn’t be topped for years.

The main difference between the two is in content: whereas A Better Tomorrow trailblazed a new style for glorious wuxia inspired gunfights, City on Fire reframed the eternal cinematic conflict between police and career criminals with a cynical pessimism that must have been startling for its first audiences. The film’s bracing story of an undercover policeman caught up with a bloodthirsty crew of jewel thieves became the acknowledged basis for America’s own neo-noir revival in 1992 when Quentin Tarantino used it as the basis for Reservoir Dogs.

Now, as part of Shout Factory’s deal to acquire the Cinema City library City on Fire is the first film in that prodigious backlog to get a 4K remaster, physical release, and placed on streaming services. For the first time since VHS was the standard, City on Fire is readily available to be enjoyed by cinemaphiles the world over in the best possible quality.

So how does it hold up?

Chow Yun-fat plays Ko Chow, a Hong Kong deep cover operative posing as a gun runner who is asked to investigate a street crew that’s already murdered one undercover officer. Chow is looking to put police work behind him after his last assignment went bad and he developed a friendship for the criminal he had to take down, and that guilt has led to the dissolution of his marriage.

Chow accepts the assignment after the crew, led by the slick Fu (Danny Lee) executes a daring daylight robbery on a jewelry factory that results in a beat cop dying. As he situated himself for a deal that will allow HKPD to capture Fu’s gang, he gets the attention of CID detective Inspector Cho (Lau Kong) who is unaware Chow is working the crew undercover. Chow is captured, tortured, and after aiding his escape Fu suggests Chow join them on their next job.

And so Fu, who opened the film killing a cop who had infiltrated his crew and Chow, a cop who wants to leave the job after befriending his last assignment move from professional respect to a doomed friendship that threatens to destroy both men as professional loyalties play against personal ones.

City on Fire is foundational to the “heroic bloodshed” and Hong Kong neo-noir movements. It contains all the major themes that will come to be developed in the Hong Kong noir over the years and to this very day: First, it posits police and career criminals to be dependents on one another, rather than adversaries with no true moral advantage. This is subtly reinforced in dialogue throughout the picture such as the scene where Chow identifies the body of the previous undercover agent as “A lowlife. A drug dealer and gun runner.” a moment before he’s asked to resume that same lifestyle in order to catch a crew of criminals. The morality of Chow’s assignment is immaterial to his superiors and in the resulting ethical vacuum the pull of genuine friendship becomes an anchor for the characters which, of course, reinforces the central dramatic tension.

Put as simply as possible: Cops and criminals become fast friends because they are more like one another, than either group is like anyone else.

Secondly, the major unspoken tension of the film is the looming handover of Hong Kong to China in 1997. Chinese crime films grew increasingly dark, anxious, and even apocalyptic from the mid 80’s all the way to the new millennium as they grappled with the implications of Hong Kong being returned to the People’s Republic of China in 1997 after a century of British colonial rule. The sense the viewer gets that the city of Hong Kong is a monster that will consume the unlucky, unable, or unwise is an interpolation of the deep anxiety of this coming sea change on the part of talented maverick directors like John Woo and Ringo Lam.

City on Fire is actually more explicit than most Cantonese films of the era in putting a name to the problem, as the entire subplot involving Chow’s wife Nam cheating on him is revealed to be naked opportunism to get a green card to Canada, and Chow’s attempt to stop her and subsequent capture sets the final, tragic, events of the story into motion.

Finally, as the name implies, heroic bloodshed films mythologize street violence into a cinematic continuation of legendary violence from Chinese classics and wuxia pulp. This can take many forms depending on the director and the film in question. Most famous is John Woo’s proclivity for slow motion gunfights with elaborate choreography.

City on Fire marries gritty realism in its camerawork with some spectacular flourishes at moments where tension is finally released: for example, the opening scene’s stabbing victim bleeding into the white sheet that’s fallen around him as he tries to escape; Chow’s escape from custody being punctuated by an incredible leap from the deck of a parking garage, and finally the Mexican standoff that closes the film’s action.

These moments of stylization elevate the emotion surrounding the violence and they draw the audience into the lawless, amoral world the characters inhabit. If you see a world where people can die spectacularly at the drop of a hat, you begin to see how valuable a single person you can trust in that world is and the central conflicts become emotionally real, even if we’re not cops or jewel thieves.

All of this is a complex means of answering the question “Does City on Fire hold up?”

Of course it does. It is that most beloved marriage in all cinema: the art house genre picture. The impeccable filmmaking of Lam is married to an energetic central performance from Chow Yun-fat that is graceful and alive and constantly surprising and it’s all in service of a script that still finds ways to suck an audience in 39 years later. See this film.

Shout Factory has put together a truly impressive package with a restored image and sound and a number of bonus features including audio commentary, interviews, trailer and image gallery.

Recommended.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login