Shout! Factory

Shout! Factory has once again delivered a love letter to genre with it’s new box set, Blaxploitation Classics, Vol. 1.

As defined by The Los Angeles Times, blaxploitation is,”the film genre, first launched by African American actors and directors in the ‘70s to show what some considered controversial slices of life in their communities.”

A film movement that defined a decade and made an indelible mark on American culture forever, blaxploitation cinema produced some of the most beloved and iconic action films of the 1970s and launched superstars along the way. This collection features such icons as Pam Grier, Fred Williamson, Issac Hayes, Yaphet Koto. Hopefully, further volumes will include the work of performers like Richard Roundtree, Jim Kelly, Jim Brown, Ron O’Neal, Tamara Dobson, William Marshall, Rudy Ray Moore, Melvin Van Peeples, Bernie Casey and Max Julien.

Let’s check them out…

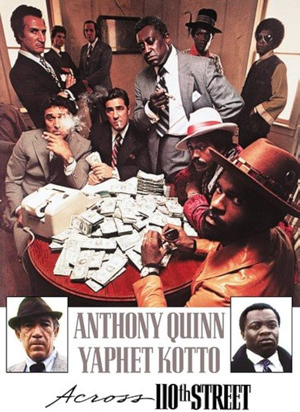

Across 110th Street (1972)

By Will McGuire

Unlike many of the major studio films made in response to the emerging independent black cinema of the early 1970’s, Across 110th Street is no lazy cash grab or simple power fantasy.

Across 110th Street is a thriller of the highest quality, using the success of blaxploitation films to ground a gritty urban noir about greed, racism, and institutional indifference in the real authenticity of Manhattan in the early 70’s.

When three black hoodlums led by local tough guy Jim Harris (Paul Benjamin) rob a Mafia safehouse in Harlem, the heist goes awry and leaves seven people dead.

The Don gives the job of retrieving the money and making an example of the thieves to his son in law Nick (Anthony Franciosa), while the police investigation is assigned to Captain Frank Mattelli (Anthony Quinn, who also produced the film) and rising star Lieutenant William Pope (Yaphet Kotto).

The film uses the manhunt as the lever by which to investigate personal corruption, institutional indifference, and the casual violence of New York in the early 70’s.

Across 110th Street clearly owes a major debt to the 1967 classic In the Heat of the Night where a straightlaced black detective of the new school is paired with a world-weary white policeman, but it also reflects all the changes in the political outlook of the audience.

Whereas In the Heat of the Night uses its rather genteel rural murder mystery as an allegory for the possibility of common ground and reconciliation between the races in the changing world of the 1960’s, Across 110th Street is governed by a kind of hopelessness of idealism scorned. The film is incredibly violent for the standards of 1972, and the characters operate almost entirely in reaction to the assumed prejudices of not only their adversaries, but their own organizations.

Mattelli’s initial objection to Pope being assigned the case can be assumed to be just wounded pride or even racial chauvinism, but it turns out to be a defensive measure to keep Pope from realizing Mattelli is, himself, on the take from the Harlem mob. This is expertly mirrored in the character of Nick, who is seen by his own subordinates as a putz who married up and resorts to common racist taunts when challenged by his black associates. This is a film about the old world dying and being replaced by the new, which by no means is necessarily better.

What keeps Across 110th Street from being an all time classic of the 1970’s is a common failing of exploitation films of the era: pacing. This is an intensely talkative, start-and-stop film that has moments of real excellence (Kotto’s Pope, in particular is hypnotically watchable) buried between very flabby exposition sequences. At 90 minutes this would be one of the best American crime thrillers– at two hours it’s merely a really good picture.

Director Barry Shear mainly worked in television, which was surprising for me to learn given how excellent all the location photography is in this film. This film soars on the streets of Harlem with crowds either gawking at Quinn and Kotto as they trade barbs or flowing about their business behind them. Every bar, every street corner, every trap house feels deeply real and grounds the polished melodrama in its time and place. This is a time capsule film in the best sense of a New York that no longer exists and a perfect double feature with The Taking of Pelham 123.

Recommended. Across 110th Street is by no means perfect, but it is a polished, violent thriller made with craft and skill that feels much more contemporary than its peers.

Extras include the documentary It’s Where The Action Is The Blaxploitation Films Of A.I.P., Part One and trailer.

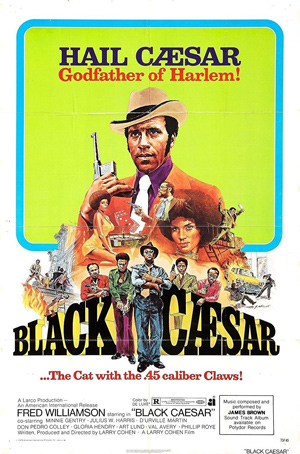

Black Caesar (1973)

By Steven Thompson

During prohibition, real-life gangsters had become almost folk “heroes” and were in the news constantly.

Their sordid, violent doings sold a lot of newspapers. Those same stories inspired hundreds of gangster movies in the 1930s and 1940s, with Warner Bros in particular making stars of the likes of James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart, and Edward G. Robinson, all in mob-based movies.

But gangster movies didn’t end there, and, in fact, had a big revival in the 1970s in the wake of The Godfather. One gangster movie from that later era, while not a full-on remake of Robinson’s Little Caesar, certainly took inspiration from it, and that is director Larry Cohen’s Black Caesar, from American International.

Just like Little Caesar put Robinson on the map and led to a prolific four-decade career, Black Caesar put former football star Fred “The Hammer” Williamson on the map and led to an acting career that, as of this writing, is going on six decades!

Black Caesar is a blaxploitation movie and, as such, has many of the tropes of that sub-genre, such as nudity, fake-looking blood, and racist white guys. It also suffers from Cohen’s direction. This was one of his first films as a director. In the street scenes, non-actors stare, point, and even wave at the camera. There’s a prolonged climactic scene that drones on for maybe 20 minutes, making it feel more comical at times than tense. Cohen got better. He was always a better writer than director, though, and that shows, here, as he’s also credited with writing this one.

The story opens in 1953 as we see a young shoeshine boy beaten senselessly by a corrupt, racist police officer. He grows up with a chip on his shoulder and 12 years later works his way into the New York Mafia. From there, he sets up his own crime syndicate in Harlem and goes after the Mafia, all with the ultimate goal of having that one police officer end up working for him.

We follow our protagonist into the present day (1972). As played by Williamson, he’s shown to be a charming, amoral monster, handsome and grinning sometimes, and yet capable of brutal rape and torture at a moment’s notice.

His enemy, the cop, however is worse! He is without a doubt one of the most violent, evil, and shamefully realistic villains I have ever seen in a movie…and I’ve seen a lot of movies. The funny part is that the role is played by Art Lund! Pretty much forgotten today, Art Lund started out as a Big Band singer. He even sang with Benny Goodman’s orchestra for a while. He had a 20 year or more career of hit records behind him before he even took up acting, first on Broadway and then in films and television. To know his beautiful singing voice and hear him growling out racist obscenities here says a lot for his acting ability.

Gloria Hendry, who co-starred around that same time in Live and Let Die and Black Belt Jones, is the leading lady. She gives a more nuanced performance here than in either of those other two pictures. The almost ubiquitous D’urville Martin gives what, to me, is his best performance here, too, as a childhood friend of Williamson’s gangster who grows up to become a preacher. There’s a brief, and much less impactful than usual, role for Julius Harris, and a particularly pointless cameo right at the beginning from familiar white character actor Andrew Duggan.

The film’s score is appropriate and quite good, although some of the actual songs are a bit of a letdown, despite the fact they come from the Godfather of Soul, himself, James Brown.

There’s no denying Black Caesar is Fred Williamson’s breakthrough, though, and he really is good! With his anachronistic sideburns and ultra-stylish suits, Fred has that classic film star charisma exuding from the screen in every scene. More than that, though, he shows that he can act, not just read lines. And he acts with his eyes. Despite his ruthlessness, he gets across how scared he is at times, how he’s still that little boy deep inside. It’s a better performance than the film requires, hurt only by the episodic nature of the story.

The aforementioned ending ensures no sequel could ever possibly be made…only they did make one and that’s up next.

During prohibition, real-life gangsters had become almost folk “heroes” and were in the news constantly. Their sordid, violent doings sold a lot of newspapers. Those same stories inspired hundreds of gangster movies in the 1930s and 1940s, with Warner Bros in particular making stars of the likes of James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart, and Edward G. Robinson, all in mob-based movies.

But gangster movies didn’t end there, and, in fact, had a big revival in the 1970s in the wake of The Godfather. One gangster movie from that later era, while not a full-on remake of Robinson’s Little Caesar, certainly took inspiration from it, and that is director Larry Cohen’s Black Caesar, from American International.

Just like Little Caesar put Robinson on the map and led to a prolific four-decade career, Black Caesar put former football star Fred “The Hammer” Williamson on the map and led to an acting career that, as of this writing, is going on six decades!

Black Caesar is a blaxploitation movie and, as such, has many of the tropes of that sub-genre, such as nudity, fake-looking blood, and racist white guys. It also suffers from Cohen’s direction. This was one of his first films as a director. In the street scenes, non-actors stare, point, and even wave at the camera. There’s a prolonged climactic scene that drones on for maybe 20 minutes, making it feel more comical at times than tense. Cohen got better. He was always a better writer than director, though, and that shows, here, as he’s also credited with writing this one.

The story opens in 1953 as we see a young shoeshine boy beaten senselessly by a corrupt, racist police officer. He grows up with a chip on his shoulder and 12 years later works his way into the New York Mafia. From there, he sets up his own crime syndicate in Harlem and goes after the Mafia, all with the ultimate goal of having that one police officer end up working for him.

We follow our protagonist into the present day (1972). As played by Williamson, he’s shown to be a charming, amoral monster, handsome and grinning sometimes, and yet capable of brutal rape and torture at a moment’s notice.

His enemy, the cop, however is worse! He is without a doubt one of the most violent, evil, and shamefully realistic villains I have ever seen in a movie…and I’ve seen a lot of movies. The funny part is that the role is played by Art Lund! Pretty much forgotten today, Art Lund started out as a Big Band singer. He even sang with Benny Goodman’s orchestra for a while. He had a 20 year or more career of hit records behind him before he even took up acting, first on Broadway and then in films and television. To know his beautiful singing voice and hear him growling out racist obscenities here says a lot for his acting ability.

Gloria Hendry, who co-starred around that same time in Live and Let Die and Black Belt Jones, is the leading lady. She gives a more nuanced performance here than in either of those other two pictures. The almost ubiquitous D’urville Martin gives what, to me, is his best performance here, too, as a childhood friend of Williamson’s gangster who grows up to become a preacher. There’s a brief, and much less impactful than usual, role for Julius Harris, and a particularly pointless cameo right at the beginning from familiar white character actor Andrew Duggan.

The film’s score is appropriate and quite good, although some of the actual songs are a bit of a letdown, despite the fact they come from the Godfather of Soul, himself, James Brown.

There’s no denying Black Caesar is Fred Williamson’s breakthrough, though, and he really is good! With his anachronistic sideburns and ultra-stylish suits, Fred has that classic film star charisma exuding from the screen in every scene. More than that, though, he shows that he can act, not just read lines. And he acts with his eyes. Despite his ruthlessness, he gets across how scared he is at times, how he’s still that little boy deep inside. It’s a better performance than the film requires, hurt only by the episodic nature of the story.

The aforementioned ending ensures no sequel could ever possibly be made…only they did make one and that’s up next.

Extras include commentary from writer/director Larry Cohen, and trailer.

Booksteve recommends.

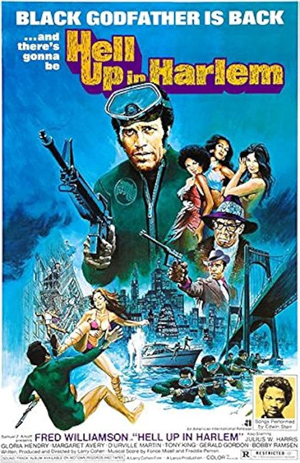

Hell Up in Harlem (1973)

By Steven Thompson

After Black Caesar was a hit, American International wanted more, and they wanted it now.

They were quickly able to re-assemble the needed cast and crew, with just a couple of exceptions. Unfortunately, those exceptions were director Larry Cohen and star Fred Williamson, both of whom were already deep into other projects.

The fact that Hell Up in Harlem is a reasonably coherent film at all is a testament to the often-unsung film editors.

Cohen reportedly worked on the film only on weekends while Williamson was doubled for numerous scenes, with his dialogue and closeups recorded on the West Coast.

A confrontation scene between Williamson and D’urville Martin’s Reverend from the first film is quite well done, despite the fact the two were clearly not in the same room. A similar scene with Gloria Hendry doesn’t work nearly as well due to clearly different setups and camera work.

One major plus of this arrangement, though, is that Julius Harris, a favorite actor of mine whose role as Williamson’s character’s father in the first picture was largely pointless, gets a major upgrade here, starting right from the beginning.

The opening credits of Hell Up in Harlem run over top of an edited version of the long ending of Black Caesar, which saw our wounded anti-hero bleeding out after being shot. In the original (SPOILER), he returns to his childhood home, now in ruins, and sees a gang of kids that seem to remind him of his own youth. They assault him and seemingly finish the job the bullet started, leaving his all-important ledgers blowing away on the wind.

For this one, he ends up at the ruins, all right, only there is no street gang, only his father, whom he supposedly called to meet him there. Instead of dying, his father contacts some people who get him to a hospital and save him. Perhaps we’re supposed to believe that the somewhat surreal ending had been all in his mind as he waited for his father to arrive. It’s never explained, and the story continues.

The main difference this time is that the swaggering gangster takes his old man into the business and Harris becomes a major player. In fact, halfway through the picture, Williamson packs up and moves out, leaving his dear old pop in charge of the Harlem rackets. He comes back for the ending, though, a long series of him shooting stuntmen.

In fact, there’s a lot of shooting all through the movie, a lot of running, a lot of driving, a short but sensuous love scene, more stolen camera shots, more swagger from the star, and a pointless subplot with Gloria Hendry that has her just wandering around until she’s written out of the picture.

Where Black Caesar was a well-done modernization of the classic gangster flicks, Hell Up in Harlem is sadly, a blatant cash grab. The mostly half-baked action sequences are surprisingly dull and one even features obviously animated blood! A few attempts at humor fall flat.

Ultimately, the saving grace here is, of course, Fred Williamson’s cocky anti-hero, but this time, it just isn’t enough to make for a very good movie, despite the genuinely impressive efforts of the film editors. This is hardly the worst movie Williamson would make, but he’s had plenty of better ones.

James Brown was brought back to do the music for this sequel but, oddly, the studio rejected it and went with Edwin Starr, then hot after his hit record “War!” His score is one of the best parts of the film.

The very best part of the film, though, was its poster, which give the impression this will be a big-budget, Bond-style action-adventure! I wanna see THAT movie!

Extras include commentary from writer/director Larry Cohen, and trailer.

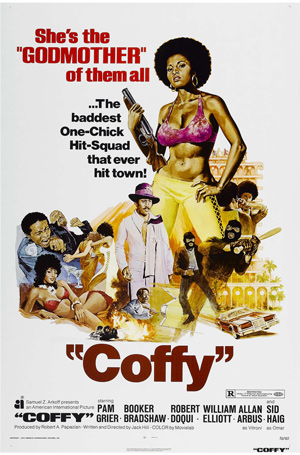

Coffy (1973)

By Will McGuire

1973 was the height of urban theater culture in the United States where theater distribution chains were breaking down outside of big cities, studios were looking for new direction and kung fu, samurai, and blaxploitation pictures were enjoying immense popularity. Films were pumped out or localized at an amazing pace, leading to mini-hits and sub-genres as peaks and valleys in the landscape of these cult genres.

Coffy is such a film: conceptualized as a pastiche of the Warner Bros. film Cleopatra Jones, Coffy has become canonized as the definitive “Girl Power” blaxploitation action picture.

The reason for this longevity isn’t hard to find, as Coffy remains the greatest showcase for its star Pam Grier ever made. Grier in 1973 was an absolute goddess: classically beautiful, full of fire, and believable in both dramatic and action set pieces. Coffy is a showcase part: a film where Grier is as central and focused to the action of the plot as Richard Roundtree was in Shaft or Bruce Lee in Fist of Fury.

Coffy opens with its titular protagonist posing as a drug addicted prostitute looking to go home with local heroin pushers, before turning the tables and killing them, revealing that her sister had overdosed and she’s out for revenge. It’s a powerful, violent opening where Coffy isn’t just out for vengeance, she’s almost sadistic in a way we’d associate with “women’s revenge” films like Ms. 45 or I Spit on Your Grave.

Satisfied that her work is done, Coffy returns to her job as a nurse where she gives her friend, Officer Carter (William Elliott) a ride home, only to find that hoods are waiting for him and beat Carter so badly he’s permanently crippled.

From this point on Coffy becomes a vigilante looking to purge the streets of the black and Italian mobs by working her way up to their bosses: King George (Robert DoQui) and Arturo Vitroni (Allan Arbus) before learning that the corruption that feeds them is a lot closer to home than she first expected.

Coffy is an exploitation film and it is certainly a “Girl Power” film written from a man’s perspective. Coffy (the character) approaches each villain with the same basic plan: seduce and destroy, and so there’s a lot of opportunity to be titillated by the film’s star.The constant juxtaposition of sex and violence culminates in an all out cat fight between Coffy and Don Vitroni’s escorts who have become jealous of their boss’ infatuation for the “new girl.”

What keeps the film from feeling as seedy as it probably should is its star. Grier gives Coffy’s rage a power and centeredness that elevates the material. Pam Grier, like Sean Connery in Dr. No, carries the film on the sheer moxy of her personality. She’s a real star, who constantly is able to surprise and captivate the audience even when the action of the plot becomes increasingly predictable.

Coffy doesn’t have the best soundtrack and the location work is pedestrian. It remains a film in the public mind because the audience had never seen a black woman hero like Grier, an actress whose sex appeal and agility as an actress captivated even white audiences at a time when a white man admitting he was attracted to a black woman was still deeply taboo in many parts of the country.

Grier rode out the blaxploitation craze before becoming a dependable character actor through the 80’s in films like Above the Law and Something Wicked This Way Comes before her career as a lead got a brief revival after the success of Quentin Tarantino’s Jackie Brown in 1997.

Coffy isn’t a great movie, but Grier is great in it and sometimes that’s enough.

Extras include commentary from writer/director Jack Hill, interviews with Hill and Grier, and trailer.

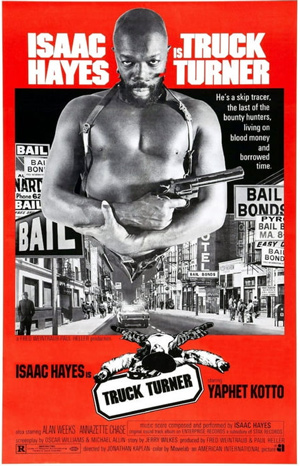

Truck Turner (1974)

By Steven Thompson

Superstar musician Isaac Hayes wasn’t much of an actor, but did anybody ever look as cool as that tall, bald, dark-skinned black man with the beard and the shades?

Surprised they didn’t have him wear his trademark chain shirt in Truck Turner. And that soulful voice! There’s no denying somebody had to star that man in a movie and this was it.

With its star as both its most appealing asset and its weakest point, Truck Turner is, in my opinion, one of the most entertaining of all the 1970s Blaxploitation movies.

It’s produced by Fred Weintraub and Paul Heller, the team behind Bruce Lee’s Enter the Dragon from the year before.

As producers, their output varied widely from solid B pictures to Grade Z schlock. This time out, they had a top-notch director, though, which clearly helps.

Beginning his career with Roger Corman’s sexploitation movies, over the following years, Jonathan Kaplan worked his way up the ranks in Hollywood.

Eventually his major releases would earn Jodie Foster an Academy Award (The Accused, 1988), Michelle Pfieffer a nomination (Love Field, 1992), and himself multiple Emmy nominations for his work on the television drama, ER. In 1974, though, Kaplan helmed Truck Turner, and was already showing he was ahead of the pack of new, young directors.

We meet Mac “Truck” Turner, who has a rep as one of the most successful skip tracers and bounty hunters around. He and his partner are hired by “That Guy” Dick Miller to bring in, dead or alive, a particularly bad pimp called Gator. After a great car chase and some sneaky tricks to find his hideout, he forces them to go with “dead.”

Star Trek’s Nichelle Nichols chews the scenery and steals the movie as the foul-mouthed madam who takes over Gator’s stable of girls after he’s shot to death. In what is possibly her most un-Uhura style role ever, she proves to be ruthless, cutting, dangerous, and yet surprisingly stylish and fashionable as she deals with all the other pimps in town attempting to buy the business.

One of the latter group is played by the great Yaphet Kotto, who makes a marvelous entrance at the funeral, immaculate in a fancy white, fur-trimmed outfit, just to spit on his late rival’s corpse.

When Nichelle’s character puts a hit out on Truck, Kotto tells her, “You’re comin’ on so strong, you’re gonna need an act of Congress or the United States Army to get Truck Turner off your ass.” Eventually, he himself agrees to get rid of Turner.

From beginning to end, Truck Turner is exciting, stylish, and well-directed, with lots of humor, interesting and unusual camera angles, great over-the-top fashions of the era, impressive sets, and a good, if not particularly memorable, score (by Hayes, of course). Besides Kotto, Nichols, and Dick Miller, the supporting cast includes veteran tough guy Don Megowan, former Our Gang member Stymie Beard, John Carpenter favorite Charles Cyphers, and familiar TV face James Milhollin. Producer Fred Weintraub gets a cameo as a judge and the wonderful Scatman Crothers appears briefly as an aging, retired procurer with a really bad hairpiece. Truck’s sidekick is played by Alan Weeks, an actor best-known for his stage work but doing a fine job here as a straight, non-humorous sidekick. This was also the first film appearance for the prolific actor and producer, Stan Shaw. Sam Laws, Paul Harris, and Annazette Chase round out the cast.

All of this more than makes up for Hayes, himself. He isn’t a bad actor, at least as far as his line reading goes. It’s just that he always seems to be waiting for his next lines, instead of maintaining his character. For a man of such presence, it’s surprising and disappointing to see that his real-life power doesn’t fully translate to playing a character. He comes across as a bit amateurish in a movie packed with a number of first-class actors.

In the long run though, that doesn’t matter so much. Truck Turner, originally fashioned for a white star such as Robert Mitchum or James Coburn, ended up as not just one of the best of the Blaxploitation films but also just a darn good 1970s action movie.

Extras include commentary with director Jonathan Kaplan, and trailer.

Booksteve recommends.

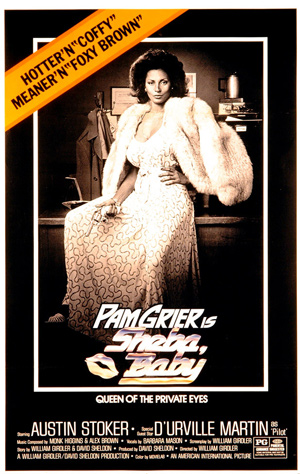

Sheba, Baby (1975)

By Steven Thompson

Pam Grier was the first black female superstar of the movies. Just three decades earlier,

Hattie McDaniel won the Oscar™ for her stereotypical role as “Mammy” in Gone with the Wind and that was Hollywood’s idea of a black woman. Meanwhile, pretty Lena Horne was having her beautiful song numbers entirely edited out of films for Southern state distribution.

Pam started out in the repetitive “women in prison” genre films of the early ‘70s but in just a couple of years had her name above the title on badass star vehicles like Foxy Brown and Coffy…and today’s movie, Sheba, Baby.

Unfortunately, Sheba, Baby is a lesser effort.

Written and directed by white, low-budget filmmaker William Girdler, and filmed mostly in his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky, if he had starred in it himself, I’d almost say it was a vanity production. As it is, it plays largely like a TV movie more than a relatively big-budget blaxploitation flick.

One thing that ties it directly to the blaxploitation genre, though, is the presence of D’Urville Martin as one of the movie’s Big Bads (Handsome white guy Dick Merrifield is the BIG Big Bad.). Along with playing sidekicks to Fred Williamson in several pictures, Martin actually directed Dolemite, one of THE most enjoyable “so bad it’s good” ‘70s movies.

The rather vague plot here sees a black mobster and his gang trying to take over a small-time loan company. Sheba is the daughter of the senior partner in the loan company. She’s just arrived back in town and also happens to be a private detective and an ex-cop. Her father is tough and resists multiple times but when he’s eventually killed, Sheba naturally takes it personally and determines to get revenge, despite warnings from the agency’s junior partner, played by Austin Stoker (Assault on Precinct 13, Battle for the Planet of the Apes).

Stoker is cool, as always, and gives a restrained performance, reading his lines better than anyone else in the picture. Pam’s okay, if not particularly impressive, but Martin could have used better direction. The lower down in the cast list you go, the more that seems to have been a problem.

One interesting performer is the “pimpified” Christifer (sic) Joy, overacting hilariously as a street loan shark who has a run-in with Sheba. His telephone scene has him being SO much like Richard Pryor that if you didn’t know Pryor wasn’t in this picture, you’d start to wonder. He had the lead in at least one film, himself. I have to find that one, now.

In the end, though, this is an action flick and the audience was here for Pam Grier. Except for the fact that there’s no nudity (something with which Pam never had an issue), they aren’t disappointed. While Sheba Shayne is not as much of an over-the-top superwoman as her previous two characters, the fact that she’s, for the most part, more relatable actually helps.

The musical score is pleasant, if unmemorable, and a little mainstream and out of character for a blaxploitation film. That said, there are several funky songs sung by Barbara Mason, the best being the title tune, “Dangerous Lady.” The beats of the song seem perfectly timed to the movement of our star’s swaying behind as she walks along. Subtle, but nice.

It’s the direction that lets down the picture. The whole thing is plodding and slow, with a long, dull chase scene through a carnival (actually the Kentucky State Fair), night scenes without any artificial lighting, a speedboat chase, and a random catfight on a yacht (a nod to women fighting in earlier Grier movies?).

Perhaps if Girdler’s PG-rated Sheba, Baby had been rated R, and had genuine grittiness to it rather than just low-budget, TV movie imitation grittiness, it would have been better. As it is, it certainly still has its moments, but they’re carried almost solely by the first black, female superstar, Pam Grier.

Sassy, stylish, and tough as nails, if you’re a fan of Pam’s, you’ll need to see it, despite its flaws. If you’ve yet to discover her magic as an action hero, you might wish to start somewhere else.

Extras include commentary and interview with screenwriter David Sheldon, and trailers.

You dig?

You must be logged in to post a comment Login