We’ve made it to 1945 in our little series here, and although we’ve reached the end of World War II, the vigorous style of war-era animation continued for several more years. The wild personality of the era even filtered its way into feature animation; Disney’s The Three Caballeros is perhaps the strangest and most psychedelic (as well as being the most sexually-charged) Disney movie ever released.

1945 might have had the greatest success rate of any year in the history of animation. At least that’s true of Warner Bros., where every single short released was a home run (then again, what do you expect when you have Chuck Jones, Friz Freleng, Frank Tashlin and Bob Clampett as your staff directors?). You know it’s a good year when I couldn’t find room on this list for such classics as Herr Meets Hare, The Unruly Hare, Trap Happy Porky, Behind the Meat Ball, Ain’t That Ducky, A Tale of Two Mice, Wagon Heels, Hare Conditioned, The Bashful Buzzard, Peck Up Your Troubles, Hare Tonic, etc.

The same might be said of MGM, where Hanna & Barbera were still churning out consistently excellent Tom & Jerry cartoons (The Mouse Comes to Dinner, Mouse in Manhattan, Tee for Two, Flirty Birdy, Quiet Please) and Tex Avery was concocting some of his most furiously brilliant films (The Screwy Truant, The Shooting of Dan McGoo, Jerky Turkey, Swing Shift Cinderella, Wild and Woolfy). The closest thing to a dud at the studio this year was The Unwelcome Guest, a George Gordon-directed Barney Bear short, and even that’s a pretty top-notch effort as far as Barney Bear cartoons are concerned.

1945 was also an exceptionally strong year for new characters. Casper the Friendly Ghost debuted in the appropriately titled Famous Studios short The Friendly Ghost. But most of the heavy lifting as far as characters are concerned came from Warner Bros.; this year, rather incredibly, saw the debuts of Pepe Le Pew (in Chuck Jones’ Odor-able Kitty), Yosemite Sam (in Friz Freleng’s Hare Trigger) and Sylvester (in Friz Freleng’s Life with Feathers)… all three fully-formed and hilarious even in their maiden voyages.

On this list, you’ll find a whole lot of Looney Tunes, as well as some masterpieces from Disney and MGM… plus, an early experiment from UPA. Take a look:

BROTHERHOOD OF MAN

Directed by Robert Cannon; UPA

UPA (United Production of America) is best known for groundbreaking animated films like Gerald McBoing-Boing (1950) and Rooty Toot Toot (1951), which showed a stylized alternative to the Disney norm and set the dominant animation trend of the 1950s. But before UPA got a contract with Columbia in 1948, the studio (which was originally known as the Industrial Film and Poster Service) was earning an income by creating design-heavy instructional films for the government and doing political work sponsored by the United Auto Workers. The first of these sponsored shorts was Hell-Bent for Election (1944), a campaign film for Franklin D. Roosevelt, directed by Chuck Jones and animated largely by moonlighting Warner Bros. animators. The film is charming and fun, but the characters are animated with a Looney Tunes-style fluidity that contrasts with the modern art-influenced backgrounds.

Brotherhood of Man was also largely created by Warner Bros. staffers – Ken Harris and Ben Washam were currently animators for Chuck Jones, Paul Julian was a background artist for Friz Freleng and director Bobe Cannon had very recently been a Jones animator – but this film doesn’t look anything like a Looney Tunes short. John Hubley largely designed the cartoon, and he gave the characters a flat, pointed look that really had no precedent in Hollywood animation. The visual style seems patterned after New Yorker cartoonist Saul Steinberg, and the short was one of the first big steps towards the modernized look UPA would spearhead in the early 1950s.

The background designs are equally innovative, with lots of flat patches of color and objects like cars and airplanes depicted in see-through line drawings. Hubley and Cannon hadn’t yet found a way to stylize characters’ movements as well as their designs, and – other than a heavy use of static images – the animation here is mostly similar to other Hollywood cartoons produced around this time (John Hubley’s U.S. Navy training film Flat Hatting, also released in 1946, shows a more creative approach to movement). That being said, Brotherhood of Man is still an extremely bold foray into a totally new look.

The film’s subject matter is equally bold. The short, which was based off of a pamphlet entitled Races of Mankind (written by Ruth Benedict and Gene Weltfish), is an educational film that calls for racial harmony and explains how there are no major differences between the races. The short cleverly depicts suspicion and contempt for other races in the form of little green men who act as shoulder devils on otherwise ordinary citizens. The film is entertaining without being overly preachy, and everything the narrator says feels like basic common sense. It may not have seemed that way in 1946, when racial prejudices of many kinds were still quite prevalent. This short is a daring and inventive work that also has something to say.

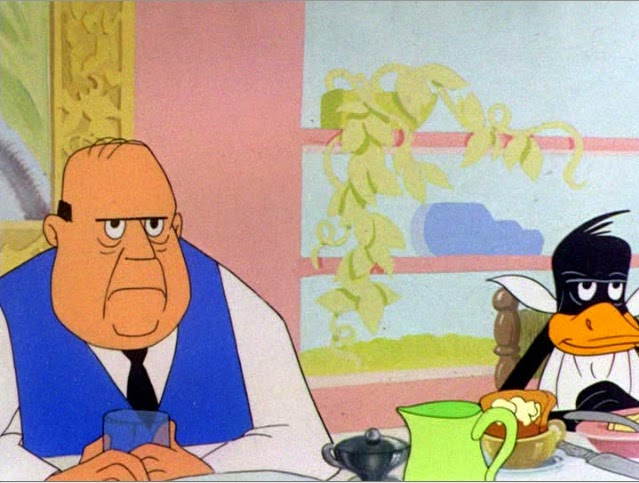

DRAFTEE DAFFY

Directed by Bob Clampett; Warner Bros.

If you were to name the ultimate Daffy Duck cartoon, you might have to go with Draftee Daffy, which features the duck in a desperate panic, trying to escape from the little man from the draft board (who frequently uses the phrase “well, now, I wouldn’t say that”, popularized by the Richard Q. Peavey character in the Great Gildersleeve radio program). The short has little in the way of plot, so it’s a testament to Bob Clampett and his incredible animators that this film remains so electrifyingly entertaining even after dozens of viewings.

The opening sequence is brilliant, as Daffy proudly sings of his national pride while dancing all around his house, impersonating Teddy Roosevelt and pretending to fire machine guns at an imaginary enemy. However, a call from the little man from the draft board sends his mood plummeting downward, and he descends into dread and self-pity. This whole sequence perfectly captures Daffy’s ego as well as his cowardly self-preservationism, and it probably summarizes many of us watching the cartoon as well, much as we may not want to admit it.

But the cartoon is just getting started, and from there, Daffy starts rocketing through his house, doing anything and everything to escape from the impossibly indestructible man from the draft board (the film nods to Tex Avery cartoons like Dumb-Hounded, where the little guy is always there no matter what you try to do to escape from him). The animation is vigorous and brilliant, and Clampett even has Daffy’s neck repeatedly expand in time to the musical beats as Daffy dashes around. Like all of the best comedy directors, Clampett takes a funny idea and keeps pushing it farther and father, and he finally pushes things so far that he climaxes by flinging his starring character into the fiery pit of Hell.

Considering the gung-ho patriotism of the war years, someone may have considered this short offensive… if it weren’t so outrageously funny, that is.

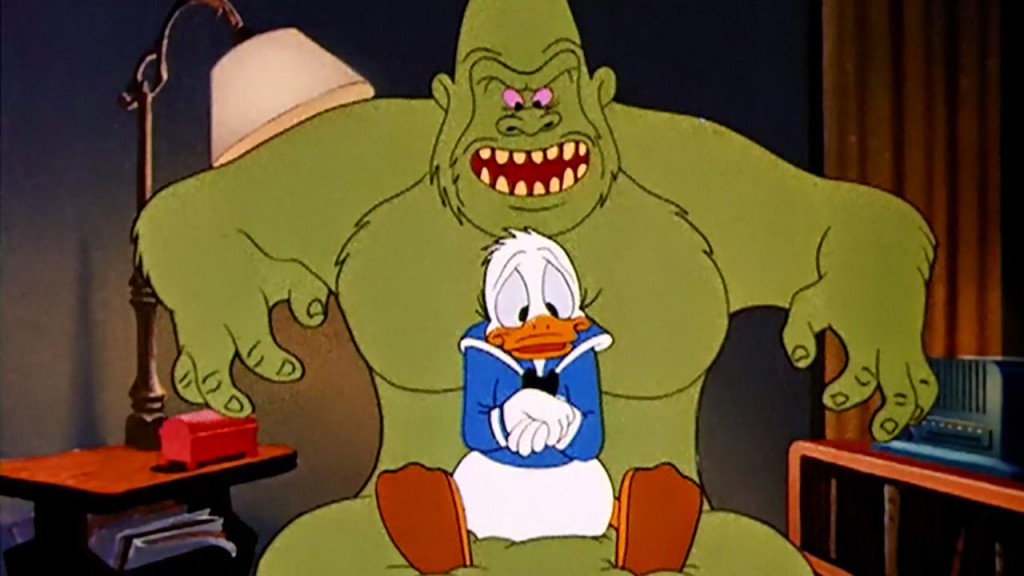

DUCK PIMPLES

Directed by Jack Kinney; Walt Disney

The Disney studio has been known to take detours into the dark and surreal – recall the Pink Elephants sequence in Dumbo or the Night on Bald Mountain bit in Fantasia – but possibly the flat-out strangest Disney cartoon ever is Duck Pimples, a Donald Duck cartoon parodying radio crime dramas and pulpy whodunnit paperbacks (the electric organ music by Oliver Wallace is a nice touch). The short marks one of director Jack Kinney’s few cartoons to feature Donald – his other two were the classic Der Feuhrer’s Face (1943) and the equally bonkers Donald’s Diary (1954) – although perhaps the true source of its eccentricity is writer Virgil Partch (VIP), best known for his outstanding and offbeat gag cartoons of the 1940s and ‘50s. His influence can be felt most strongly in the design of the man in the raincoat, who looks like he stepped right out of a Partch cartoon.

Duck Pimples feels almost like a dream in the way characters appear then disappear, going on weird tangents while eventually returning to a few key themes. Also like a dream, Donald himself takes a backseat in the shenanigans, mostly reacting to the various oddballs and lunatics who wander into his living room. The short is full of absurd visual gags and oddball transformations, in many ways feeling like a 1940s update on surreal pre-code animated films like Fleischer’s The Herring Murder Case (1931) and Ub Iwerks’ Spooks (1932). You know this isn’t your typical Disney cartoon when one character rides around on an invisible bicycle (and fades into ether when his usefulness in the cartoon is over) and an attractive girl pulls a fish out of another character’s sock. I particularly love the way the backgrounds transform into a totally different setting whenever a new character enters, resembling the ever-shifting locales of Coconino County in George Herriman’s Krazy Kat comic strip.

The animation in the film is unfailingly excellent, from the flat-headed Leslie J. Clark (named after animator Les Clark) to the Billy Bletcher-voiced Irish detective H.U. Hennesy (named after layout artist Hugh Hennesy), not to mention Dopey Davis’s little nose twitch when he sees the cops are after him. Perhaps best of all is pale white femme fatale Pauline, most likely animated by the great Milt Kahl, who is one of the best girl characters to ever feature in a Disney film, with just the right mix of sexiness and comedy. For anyone looking for a stranger, seedier side to the Disney cartoons, this is the film for you.

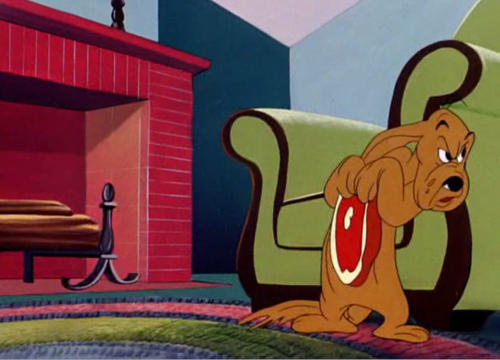

FRESH AIREDALE

Directed by Chuck Jones; Warner Bros.

Any write-up on Chuck Jones is sure to list films like What’s Opera, Doc?, Duck Amuck, One Froggy Evening and Rabbit of Seville as his finest achievements, and all of those shorts certainly deserve their status as masterpieces. However, one Chuck Jones classic that doesn’t come up nearly enough is Fresh Airedale, one of the most cynical black comedies ever to emerge from the Warner Bros. studio, and also one of the most bitingly funny. Like One Froggy Evening, the film is a little one-shot parable about human nature and it still packs a massive punch.

The story concerns a dog named Shep who is adored by his master despite the fact that he is a hateful, disgusting hypocrite, and the film shows us how he steps all over the innocent house cat and everyone else to get his way. The film is an absolutely brilliant exercise in frustration, with Shep proving himself to be an even bigger louse in every scene. His horribleness is wonderfully exaggerated for comedic effect, as he growls menacingly to no one in particular over the possession of a piece of steak (what a great drawing that is) and his shoves more and more food into his gut. But Jones keeps pushing things farther, eventually having him assist in a robbery and even attempt to murder the country’s No. 1 Dog (originally Fala, President Roosevelt’s dog, but changed at the last minute as a result of Roosevelt’s death).

A film of this kind could’ve easily boiled its characters down to ciphers to better make its point, but this is where Jones’ incredible directorial skills truly come to life. The characters’ poses and expressions nail every thought and emotion with stunning perceptivity, and their personalities are fully fleshed-out despite their extremeness. Shep is so bent on getting away with cruelty that he seizes opportunities he can’t possibly care about; he greedily devours all of the meat given to him without even enjoying it, and insists on stealing more when the situation presents itself despite the fact that he is clearly stuffed. We’re even given a glimpse into Shep’s mind during the surreal “No. 1 Dog” sequence, a graphically daring bit that owes a lot to Jones’ work on stylized, educational films for the army during WWII. Even with the innocent cat character, Jones avoids blanket simplicities: when the cat gives up his fish bone to his master, he seems comically pleased with himself and his Good Samaritanism, rubbing his head on his own shoulder as if to say “aw shucks, it was nothing”.

Jones and Maltese here craft a masterful satire, not based on anyone specific (that we know of) but aimed at gross injustice in general. The master is predisposed to assume Shep is honest and loyal and the cat is a “contemptible sneak” because of his assumptions about their species in general, blisteringly skewering not only unfair prejudices, but also blind hero worship; the world can’t stop hailing Shep as a great hero, unwilling or unable to comprehend that he may have used insidious means to gain his reputation. Director Preston Sturges made some similar points in the previous year’s satirical masterpiece Hail the Conquering Hero, but Fresh Airedale is every bit as funny as that film and even more uncompromising. It ends on a bleak and thoroughly jaded note that promises swindlers will continue to be idolized by a brainless populace, and those truly deserving of accolades will wind up with mud on their faces. One wonders how this cartoon got by the Production Code, which insisted that criminals be punished and justice upheld. There is certainly no justice to be found in a film like this.

A GRUESOME TWOSOME

Directed by Bob Clampett; Warner Bros.

In this outstanding Tweety cartoon – his third appearance, following A Tale of Two Kitties (1942) and Birdy and the Beast (1944), and his final film with creator Bob Clampett at the helm – a dumb yellow cat and a feline caricature of Jimmy Durante compete for the affections of an attractive girl cat. She eventually agrees that whoever can bring her back a little bird can be her fella, and that’s where Tweety enters in.

This film features Bob Clampett in absolute peak form, and it’s a marvel to behold the cartoon’s unbridled lunacy and exhilaratingly stretchy animation, provided by the likes of Rod Scribner, Manny Gould and Robert McKimson. There’s a pretty heavy amount of cartoon violence here, even for a Warner Bros. cartoon, but Clampett knows how to use this extremeness to deliver laughs: in one memorable scene, the two cats freeze in mid-air, brandishing guns, knives and medieval torture devices, only to deny that they were fighting. Just about every shot contains a ton of hilarious drawings and visual innovations, and the animation of the stretchy, sagging horse costume (boldly colored pink) is gleefully distorted by Clampett and his team, culminating in a brilliant final shot of the horse twisting and expanding off into the distance after a bee has entered the costume.

These crazy visual gags are Clampett’s bread and butter, of course, but the film is also excellent from a writing standpoint; one scene, which mangles the word “strategy”, is quite funny in terms of character and also makes a clever comment about how over-confidence can fool people into thinking you know more than you actually do. Clampett sneaks a subtle innuendo into the film as well, having the Durante cat explain to us that he’s “the horse’s head”, and leaving us to imagine the dumb cat’s comment about what he is. There’s also one great gag that surely ranks as one of the best to ever appear in an animated film, in which a dog who admits that he doesn’t actually belong in the picture invades the film to seize an unrealized opportunity.

Tweety is as adorably sadistic here as he was in his first appearance, slapping a bee and throwing it into the cats’ joint costume and creaming a bulldog with a bone just to get him angry. His delighted expression after he says “them fall down go BOOM” perfectly summarizes his balance of over-the-top cuteness mixed with a dollop of psychosis. He is even given his own little theme song based on his distinctive catchphrase “I Tawt I Taw a Puddy Tat”. But Tweety doesn’t have to steal the show here, as the two feuding cats are funny enough on their own. They make a hilarious comedy team, and it should come as no surprise that Ren and Stimpy-creator John Kricfalusi wound up landing a design for Stimpy after doodling the cats from this very film.

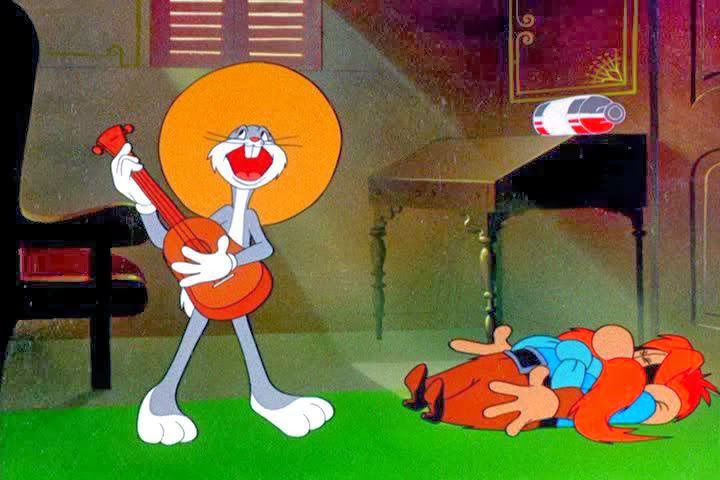

HARE TRIGGER

Directed by Friz Freleng; Warner Bros.

Developing a successful character in any format is a difficult task, and it usually takes a couple of misfires before the formula is perfected. Certainly the earliest experiments with Bugs Bunny, such as Porky’s Hare Hunt (1938) and Hare-um Scare-um (1939), show a lot of room for improvement. But Friz Freleng managed to nail an iconic cartoon star on the first try twice in one year. He did it with Sylvester in the brilliant dark comedy Life with Feathers, and he did it with Yosemite Sam in Hare Trigger, one of the best debuts ever and on the top-tier of great Bugs Bunny cartoons.

This film, which features a showdown between Bugs and Sam on board a train, is a masterful battle of wits between two very funny characters. The cartoon is full of wonderful comedy sequences, such as the bit where Sam attempts to “draw” a gun and the scene where Bugs stages a fake gunfight while sitting on Sam’s head. These are funny sequences, but it’s the little touches of character that make all the difference; check out Sam’s intensely focused expression as he draws (brilliantly coupled with some basic keys on the piano from Carl Stalling), or the way Bugs impatiently grabs Sam’s guns to show him which direction to fire as he leads him astray. The short is also remarkably inventive, even tossing in bits of live-action for comic sparks.

But the greatest comic sparks come from Yosemite Sam’s irascible personality. His over-the-top bluster, performed with gusto by Mel Blanc, makes him a great foil to Bugs. The character may have been partially inspired by Red Skelton’s radio character Sheriff Deadeye, but Freleng cited inspiration in an earlier Tex Avery cartoon Dangerous Dan McFoo (1939), in which the villain screamed all of his dialogue at the top of his lungs. Another Yosemite Sam precursor appears as a southern sheriff in Freleng’s own Stage Door Cartoon (1944). However, writer Michael Maltese claimed he based the character off of Freleng himself, who also had red hair, was somewhat short in stature and was known to be quick-tempered. It was a match made in heaven, and throughout the studio’s golden age, Freleng was the only director to make use of Sam.

Freleng wanted to create a new antagonist for Bugs because he felt that Elmer Fudd was too dumb to really challenge the rabbit. Not that Bugs has to break much of a sweat heckling Sam either, but his volatile personality gave him the air of being more dangerous and makes Bugs look all the cooler in dispatching him. In fact, the ending of the film mocks the very idea that Bugs could ever be in real danger in its parody of “cliffhanger endings”, common in movie serials of the time. No matter what impossible odds are put in front of him, Bugs will unfailingly come out on top.

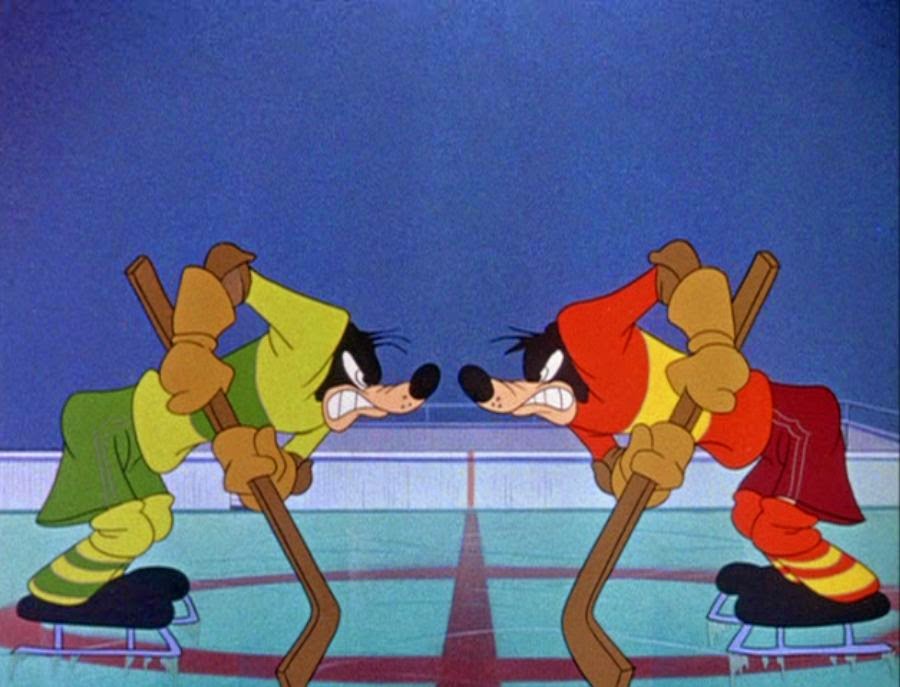

HOCKEY HOMICIDE

Directed by Jack Kinney; Walt Disney

Director Jack Kinney got a lot of mileage out of the How-To format in the 1940s, resulting in hilarious masterpieces like How to Play Golf (1944) and How to Play Football (1944), but the high point of the series was this outlandish attack on the game of hockey. Perhaps the brutal nature of the sport inspired the artists, or perhaps this film just happened along when Kinney’s skills were at their peak, but the slapstick comedy here is pushed to the absolute limit. The animation in this film is beautifully zany and the short winds up spinning out of control as no other Disney short has before or since.

The cartoon is expertly narrated by Doodles Weaver, who joined Spike Jones’s City Slickers the following year and provided similarly fast-paced patter on famous recordings such as a horse race parody of the William Tell Overture. His ceaseless banter helps to build momentum, and it matches perfectly with the speedy gags and zany animation, provided by greats like John Sibley and Milt Kahl. Speaking of which, Sibley, Kahl and a host of other animators get name-dropped in this very in-jokey film. A score-card lists such names as Kewpie Nichols (in reference to director Charles Nichols), Slugger Hannah (in reference to director Jack Hannah), Hurricane Smith (in reference to studio musician Paul J. Smith), etc. The two star players in the film are Fearless Ferguson (animator Norm Ferguson) and Ice Box Bertino (story artist Al Bertino), and one fan gets yelled at for cheering on Riley (background artist Art Riley). Jack Kinney even parodies himself as referee Clean-Game Kinney, who is loudly booed by everyone.

The short is spilling over with riotous jokes, all executed with breakneck energy. There are some wonderful running gags in the film, such as the two Goofy acquaintances in the stands who are cheering for rival teams, and Clean-Game Kinney getting violently assaulted whenever he drops a puck on the ice. And funniest of all is Ferguson and Bertino constantly getting pulled in and out of the penalty box for brawling. But the short really goes haywire during the insane climax, where a whole load of pucks get dropped onto the ice and it’s every man for himself. Quick shots of Goofys attacking each other are interspersed with bits of animation from other ill-fitting Goofy cartoons like How to Play Baseball and How to Play Football, just to add to the hysteria. Best of all is a shot of Monstro the Whale from Pinocchio, inserted for no reason at all.

This short was in many ways the climax of the How-To series; immediately following this film, Kinney shifted to working on features for several years and Jack Hannah-directed entries like Double Dribble and Knight for a Day couldn’t capture the same spirit. But perhaps Kinney couldn’t have, either. With Hockey Homicide, he may have pushed the series as far as it could possibly go.

MOUSE IN MANHATTAN

Directed by William Hanna & Joseph Barbera; MGM

It’s hard to believe after seeing Magilla Gorilla or Jabber-Jaw that there was ever a point when Hanna and Barbera were willing to take risks, but here we have a unique twist on the Tom and Jerry shorts, produced for no apparent reason except that the directors wanted to try it. This is really a Jerry solo cartoon, where Tom is featured briefly at the beginning and end but doesn’t figure into the film’s plot. It isn’t overflowing with gags like your typical Tom and Jerry short, but it has a magic to it all the same.

The film, which is sort of a twist on the fable of The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse (only without the town mouse), shows Jerry leaving his drab suburban residence in favor of life in the big city, only to find that there’s no place like home. The cartoon was released the same year as Jerry’s famous dance with Gene Kelly in the feature film Anchors Aweigh, and it demonstrates what a good fit the two were, as this short has the same irresistible charm as the finest Hollywood musicals of the ‘40s and ‘50s. The backdrops are classy and strikingly evocative, and Scott Bradley’s wistful George Gershwin-inspired score is one of the best he ever composed.

But none of this would matter if it weren’t for the ingratiating characterization of Jerry, who is masterfully brought to life here by some of the best animators in the business. His strong likability allows you to take on the perspective of a little guy lost in a big city, and as a result the film is one of the finest and most original tributes to New York City ever put on film. All the more impressive that Hanna and Barbera were able to craft such an emotionally resonant short without relying on a word of dialogue or even big gags. The next time you hear someone dismiss the Tom & Jerry cartoons as the worst sort of mindless violence, direct them to this wonderful film, which really does live up to the MGM mantra of art for art’s sake.

NASTY QUACKS

Directed by Frank Tashlin; Warner Bros.

Surely one of the greatest performances from Daffy Duck, and possibly the crown jewel of Frank Tashlin’s directorial career, Nasty Quacks is a masterful domestic comedy jam-packed with great gags, strong character work and highly experimental visuals. It seems a travesty that Tashlin’s name is listed nowhere on the credits for this film, although he left the studio shortly afterward and Warner Bros. had a habit of leaving off the credits of departed employees (and perhaps Tashlin wanted it this way; he left the studio to pursue a career as a live-action screenwriter, and having his name bannered over wacky duck cartoons may not have been a boon to his career).

The short portrays Daffy as an obnoxious family pet, greatly loved by young Agnes and bitterly hated by Agnes’s father, who would do anything to get rid of him. Daffy is in a great period here, having moved away from his early lunatic phase a la Porky’s Duck Hunt, but not quite at the point of being the selfish coward of the 1950s. Here, as in other amusing cartoons like Chuck Jones’ A Pest in the House (1947) and Robert McKimson’s Daffy Duck Slept Here (1948), he is portrayed as an abrasive boor, full of restless energy and quick to get on everybody’s nerves, intentionally or not. The scenes where he relates the events of a wild party he attended, as Father sits by with the greatest expression of stone-cold irritation ever drawn, is one of the duck’s defining moments and is a high point in the career of voice artist Mel Blanc. Daffy’s arrogant heckling of the father giving way to panicked desperation upon being replaced reveals Daffy to be one of the most strongly conceived and highly developed characters ever to grace animation.

Of course, in addition to great dialogue and voicework, Daffy is ingeniously brought to life by Tashlin’s strong poses. Tashlin’s work always had a pointed, angular look to it, but this is perhaps the most extreme example, with its heavy use of straight lines, jagged edges and rapid shifts from one pose to the next, boldly animated by the likes of Arthur Davis and I. Ellis. The film feels worlds away from the squashy, spherical animation produced by Disney animators like Fred Moore and Bill Tytla (note: that is not a knock against those paragons of character animation, only a comment on differing styles). In fact, Nasty Quacks strongly anticipates the Cartoon Modern look many studios would adopt in the 1950s. But unlike the serene and harmless worlds brought to life in the UPA cartoons, Tashlin uses the stylization for expressly comic purposes.

Such a look perfectly suits the inherent cynicism of the story. As opposed to simply being annoyed with Daffy’s antics, the father here truly detests Daffy, and the sting of this is emphasized by the mock cheeriness of the opening narration. Daffy is described as being “just like one of the family”, and the short then proceeds to show the dark side of family, in which you have to constantly put up with the inane hijinks of people you actively dislike while they mooch off of you. The short also avoids sentimentalizing the relationship between Daffy and Agnes, as the cartoon portrays “Aggie” as a broad caricature of a talkative child, quick to drop Daffy when a newer replacement comes along. Murder and sex eventually enter the story, taking an already wild film into racier territory, to great effect. In terms of animation, writing and strong characterizations, this film should be studied as an example of film comedy at its finest.

SWING-SHIFT CINDERELLA

Directed by Tex Avery; MGM

Avery’s outrageous follow-up to the 1943 classic Red Hot Riding Hood takes on the story of Cinderella, with the wolf this time chasing after the titular “fairly tale fireball” while avoiding her horny old fairy godmother. Avery had already taken on the Cinderella legend in his 1938 Warner Bros. cartoon Cinderella Meets Fella, and while that film was a highlight of his early output, Swing-Shift Cinderella is a good demonstration of how dramatically Avery had improved as a director in under a decade. For that matter, Avery’s directorial skills had even sharpened considerably since Red Hot Riding Hood.

Ever since Avery arrived at MGM, his films were full of funny drawings and fast-paced gags, but his earliest films at the studio contain a few nods to the Disney style in their beautifully lush animation (not surprising, given that many of his animators had previously been working for Hugh Harman). As the ‘40s wore on, Avery’s personal drawing style began to grow in dominance over his own films, and his characters became flatter and more stylized; compare the fluid, three-dimensional treatment of the grandma in Red Hot Riding Hood to the sticklike fairy godmother seen here. This economical style gives Avery even greater freedom to distort his characters, and great gags like the wolf’s body collapsing in a mangled heap after falling out a window and the wolf drilling his head through a wall wouldn’t have played nearly as well only a year or two earlier.

And it isn’t just Avery whose skills have improved. Animator Preston Blair thoroughly tops his animation of Red in the previous film with the nightclub sequence here. The song is “Oh Wolfy” (a variation on “Oh Johnny, Oh, Johnny, Oh!”) sung beautifully by Imogene Lynn, and the bit is so good it was reused in a later Avery classic Little Rural Riding Hood (1949). The performance is more nuanced than before, but Blair maintains the caricature element, and the girl never comes off as an imitation of real life the way many “sexy” animated characters inevitably do. She is just as comfortably an animated creation as the more insistently cartoonish wolf. And speaking of the wolf, his reactions to her increased sexiness are appropriately made even more extreme. Perhaps the film’s funniest moment is when the wolf first encounters Cinderella, and his speech smoothly trails off into panting gibberish before he rockets into a nearby tree, whinnying like a horse and madly whacking himself in the face with his own foot.

But there are many great moments to rival that one, as the hilarious ideas in this film come fast and furious. Avery doesn’t even pretend to be interested in the fairly tale story, simply using it as a jumping-off point for his own madcap humor. There’s a great gag at the beginning where Red Riding Hood shows up in the wrong picture, a meta-joke to rival the one at the beginning of Red Hot Riding Hood. There’s outrageous cartoon slapstick by the truckload, with characters constantly getting bashed with mallets and frying pans. And there’s World War II topicality, as in the final gag that reveals Cinderella is a Rosie the Riveter who has to leave the ball at 12 to make her midnight shift at Lockheed (or “Lockweed”). It doesn’t get much funnier than this.

Any comments or suggestions for this post? What are your favorite cartoons of 1945? Let me know in the comments below.

![]()

![]()

You must be logged in to post a comment Login